'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the world

Where else on Earth can you find more than 752,000 acres of splendid isolation? Words and pictures by Luke Abrahams.

It’s some ungodly early hour on a Monday morning and I am in the foulest mood imaginable. Cooped up at the back of an overcrowded and chaotic Latam flight bound for Balmaceda airport, I am surrounded by screaming children, their twitching parents and hench South American studs who don’t fit in their seats. I have no window to look out, nothing with which to find my bearings and I am — like the screaming children’s parents — ready to check myself into the nearest nuthouse. Eventually, sweet solace comes in the form of touchdown. The airport is small, dinky and blissfully isolated. There’s only one baggage belt, and onto it emerges a mess of bikes and hiking kit — all the gear required to take on our planet’s greatest wildernesses. Chilean Patagonia.

The extreme remoteness of this slither of grand coastline that runs down the eastern flank of the Pacific Ocean has been an adventure hotspot for decades, despite it being an absolute nightmare to reach. I’d arrived in Chile five days prior following a stint in the very dry and very hot Atacama Desert, but before that I’d clocked up several thousand miles via a 45-minute journey through central London to Heathrow, a 15-hour airplane ride to Santiago and three domestic, and very turbulent, flights to and from (and back to) the desert to the northern Patagonian ice sheet. The final leg of this odyssey was a seven-hour car journey along 300km (about 186miles) of mostly unpaved roads of The Carretera Austral (Chile's famed Route 7). Was I ready for it? Absolutely not.

For the first hour of my drive the wind was so ferocious, the clouds so huge, snagging over mountain peaks, and the rain so heavy that it was like a message, loud and clear, that Pachamama believed me to be unwelcome. Eventually, the skies broke to reveal a luminous rainbow arched over the Austral Valley. It was a moment best summed up as pastorally poetic. Thick forests and clusters of small towns tumbled by and we eventually hit Lago General Carrera, the largest and deepest lake in Chile. A vision of electric blue, it’s so vast that we spent a whole two hours driving alongside it. And then my final destination. Parc Nacional Patagonia. Desolate, remote and cut off from civilisation during the winter months thanks to the razor-sharp glaciers of the Northern Patagonian Ice Sheet, this wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks like Torres del Paine cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness.

This is the heartland of the Chacabuco Valley, in the Aysen region of Chile. The landscape is desolate and the only sign of life on the glacier-capped horizon are a few guanacos, the odd-looking llama-like creatures who have become the national symbol of these gargantuan lands that cradle the ends of the earth. Decades before, it would have been near impossible to see these majestic beasts roaming so freely as this entire swathe of Patagonian expanse was severely overgrazed by gaucho farmers. Remnants of their existence are still visible, mostly in the form of my Explora lodge, a former cattle farm that was overhauled by founder and Chilean entrepreneur, Pedro Ibáñez back in 2021. It is the park’s only inn and the set-up is best described as wild west meets Ralph Lauren. There are 17 rooms and suites. The cushty rugs are plentiful; the giant windows bizarrely soulful; the woodcarvings in the rooms, lavish; and the cosy poof game by the fire, undoubtedly strong. The real reason people get all besotted with the place? That 752,000 acres of splendid isolation.

A guanaco: relative of the llama and one of Patagonia's 'Big Five'.

Here, among the bushes, wild grasses and thick lush forests, elusive puma run free, giant condors score the skies, endangered Andean hide in the woods and Ñandú – a type of South American ostrich so rare that only 1% of Chile’s population have seen them — thrive in the dry pampas near the Argentine boundaries of the concession. It was this vision of natural splendour that entranced the late Doug Tompkins and his wife Kristine, the American founders of the National Park, most.

‘Doug and I used to travel to Argentina every summer and pass through this jewel of a valley called Valle Chacabuco, says Kristine, ‘getting permission to camp from the estancia (local ranches). Picture a huge east-west grassland surrounded by mountains and tiny lakes. It was pretty special to us. When they decided to sell, we saw an incredible opportunity — to recover these immense grasslands for native species, like the guanaco, Darwin's rhea and puma, but also to connect it to existing parklands of lesser status to the north and south, creating one enormous park.’

In 1994, the couple founded Conservación Patagónica (on December 31, 2018, Conservación Patagónica became the Tompkins Conservation), a conservation group with a mission to save and restore wildlands across Chile and Argentina. Their credentials, by the way, speak for themselves: Doug made his fortune with clothing companies The North Face and Esprit, and Kristine was the former CEO of Patagonia. And conservation was always at the heart of their Patagonian love story; much of the restoration, Kristine tells me, was down to their own immense undertaking.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Explora Lodge, a testament to Douglas and Kristin Tompkins’ legacy, is nestled in the Chacabuco Valley.

‘Patagonia National Park is emblematic of all the ecosystems that the region has to offer, from vast steppe, to Andean peaks, forests, rivers and lakes. It has all the elements that we look for in conservation: big, wild and connected, so species have room to roam. It’s also important to local communities, not only to live some place where the soil, water and air are intact, but also as a source of economic vitality. Parks help communities establish regenerative economies that benefit both people and nature in the long term.’

Initially owned privately and operated as a public-access park, in 2018, Patagonia National Park was donated to the Chilean Government by the Tompkins Conservation. The project has been challenging because overgrazed pastures do not bounce back overnight. ‘Depleted forests were rewilded by enriching severely degraded soil and more than 500 miles of fencing was removed so that all the animals could move freely between the park, federal and private lands via wildlife corridors,’ explains Kareen Hoffenberg, the guest experience manager and matriarch of Explora’s lodge. In addition, the ranch’s remaining sheep had to be gradually sold off; as a result, the park’s grasslands slowly returned to their former glory. In time, the native wildlife returned to take their place. Kareen admits that there was ‘resistance’ from the local population, but thanks to high re-employment whereby poachers are now rangers and gauchos are trained conservationists, all but one family is now on side.

It might sound like a success story, but the park is still relatively unknown, especially in contrast to Patagonia’s other National Parks — especially Torres Del Paine and Parque Nacional Los Glaciares. There are no crowds here, and though the lodge is often full, you are unlikely to bump into one of them whilst out exploring the valley it calls home. More fool everyone missing out because this rare blend of landscapes — from dry desert to beech forest, vast lakes that cradle some of the clearest and cleanest waters on the planet to ice fields — make it one of the most unique spots on the entire Patagonian shelf.

While out on the hunt for Andean deer (to look at, not to kill) with my guide Micaela Diaz Rossi, we encounter panoramas millions of years in the making. Continuously shifting tectonic plates has resulted in utterly unique geological formations. What was once an ancient coral reel is now a sedimentary basin that fuels plant life: wild strawberries, yarrow and dandelion, lichen, old man’s beard, Turkey tail fungus and Chinese lantern, to name just a few.

On a hike to the Baker and Chacabuco Rivers, with a guide called Pablo Andres Vega Ortega, I learn that the park’s beauty conceals a dark history. The Patagon, the park’s original settlers, were wiped out by European colonists. Disease, extreme violence and a near total erasure of their belief system means that nearly every trace of their 8,000-year history has vanished into the ether. Pablo describes the events as ‘a cultural genocide of displacement’. The wounds are still raw — but some of the Patagon’s myths, legends and Gods preserved via monuments, monoliths and the Patagonia National Park Museum.

And then there is the night sky.

On my final evening, I ventured outside to a celestial masterpiece. Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn all in near perfect alignment and served up for me on a dramatic canvas, stained blood red by the slowly setting sun. I stared at it for hours, until the sky was inky black and I was at risk of being bitten alive by an army of insects. In this part of the world, even the naked eye can make out distant galaxies and shooting stars fall in between countless moving satellites. I remember what an American woman called Carol said to me days before in the Atacama Desert: ‘I never look up at the night sky, Luke. It terrifies me. It makes me feel so worthless, and so small, and so insignificant that I start to question everything.’ I too was stuck in some kind of philosophical state, but unlike Carol, this divine sight was more comforting than frightening. I was on an ultra high definition interstellar voyage that topped every experience I had had in the last few days. It was, in every sense of the word, unique.

On my return drive, I received a text message asking me if I’d intended to leave my very full laundry bag on the bed. Fourteen pairs of underwear, a lot of shirts and some jumpers are currently on a boat bound for the UK — on an epic journey of their own.

Luke Abrahams was a guest of cazenove+loyd which can organise seven-night trips to Patagonia National Park from £6,650 per person based on two people sharing. The cost includes five nights at Explora Patagonia National Park on a full board basis as well as all excursions, transfers, accommodation in Santiago and domestic flights.

Luke Abrahams is a freelance journalist based in London. He specialises in luxury lifestyle journalism, with an emphasis on sustainability, spirituality, culture and history. His work has appeared in 50 global titles across several markets, including British Vogue, Harper's Bazaar, The Times, Condé Nast Traveller, Wallpaper*, ELLE, Town & Country, The Telegraph, Travel + Leisure and House & Garden. He has visited 120 countries and, along the way, has learned the beautiful art of perspective. Italy will always hold a special place in his heart. When Luke is not writing, he often spends most of his time enjoying long walks or long baths.

-

'Comfortable, cosseting and far from the madding crowd': The recently refurbished Cornish cottage that proves Victorian decor is making a comeback

'Comfortable, cosseting and far from the madding crowd': The recently refurbished Cornish cottage that proves Victorian decor is making a comebackPlum Cottage in Padstow, Cornwall, has been brought to life by Jess Alken and her husband, Ash — and is the latest addition to their holiday cottages on the north Cornish coast.

-

How to make The Connaught Bar's legendary martini — and a few others

How to make The Connaught Bar's legendary martini — and a few othersIt's the weekend which means it's time to kick back and make yourself an ice cold martini — courtesy of The Connaught Bar.

-

The pristine and unspoilt English county that 'has all the ingredients of perfection'

The pristine and unspoilt English county that 'has all the ingredients of perfection'Many people simply pass straight through Northumberland heading for Scotland. Big mistake, says Matt Ridley.

-

The extraordinary Exe Estuary, by the Earl whose family have lived here for 700 years

The extraordinary Exe Estuary, by the Earl whose family have lived here for 700 yearsCharles Courtenay, the 19th Earl of Devon, shares his own personal piece of heaven: the Exe Estuary in Devon.

-

‘So old-fashioned, it’s new-fashioned’: Riding the rails on the Belmond Royal Scotsman

‘So old-fashioned, it’s new-fashioned’: Riding the rails on the Belmond Royal ScotsmanWhat goes around, comes around, says Steven King of a trip through Scotland to celebrate 40 years of the Royal Scotsman, A Belmond Train.

-

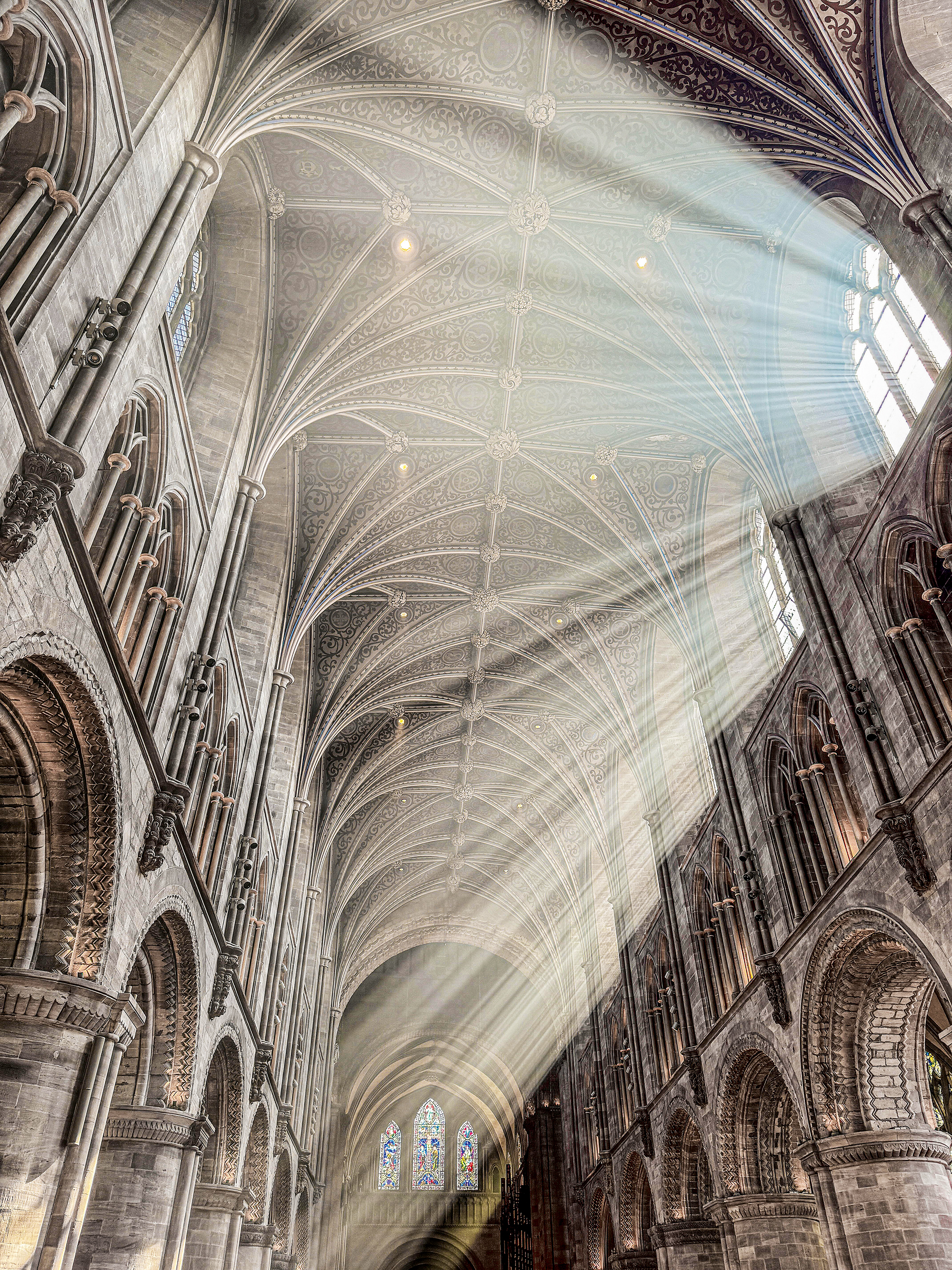

Quentin Letts: Heaven in Herefordshire

Quentin Letts: Heaven in HerefordshireQuentin Letts is best known as a merciless sketch writer and critic — but when he's back home at Herefordshire he embraces a very different life.

-

The Manner review: This New York hotel is bringing the 1970s back to SoHo, one colour at a time

The Manner review: This New York hotel is bringing the 1970s back to SoHo, one colour at a timeThe Manner, on one of SoHo's quieter, tree-lined streets, is proof that great hotel design can make or break a holiday.

-

My piece of heaven: The Vale of Belvoir by Lady Violet Manners

My piece of heaven: The Vale of Belvoir by Lady Violet MannersLady Violet Manners, who grew up in Belvoir Castle, shares her love of the area around her ancestral home.

-

At His Majesty’s pleasure: A woodland retreat for rent at Sandringham

At His Majesty’s pleasure: A woodland retreat for rent at SandringhamWith room for six guests, and with 20,000 acres on the doorstep, it would be folly to not get booking.

-

The East African holiday hotspot that should be top of your travel wishlist — and where to stay

The East African holiday hotspot that should be top of your travel wishlist — and where to stayThere's more to Kenya than just safari.