The extraordinary tale of Hadrian's Wall: 'Men have been deified for trifles compared with this admirable structure'

What once kept out hordes of bloodthirsty warriors is, nearly 2,000 years later, barely proof against the most timid of sheep. But if Hadrian’s Wall is now low on stature, it remains high on atmosphere, says Harry Pearson.

To look north-eastwards from Walltown Crags in Northumberland is to gaze upon an English wilderness. The ashen cliffs of the Whin Sill drop 75ft to a brindle-coloured plain that stretches far into the distance, its surface broken by patches of dark heather and the occasional glistening black splash of groundwater. What few trees survive are small and stunted, hunchbacked against a prevailing westerly wind that rattles the bent grass and sends crows somersaulting across the vast grey sky. The cawing corvine protests are the only sound of life. To stand here on a swirling day in winter (and winter goes on for a long time here) is to feel as our ancestors must have done: tiny in a big world. The Romans who arrived here in the first century looked at it and felt they had reached the lip of civilisation. They called the place Ad Fines — the End of the Earth.

Yet, despite that, the Romans came there in their tens of thousands and stayed for close to 300 years. Face east or west from Walltown and you look along their great legacy, a knobbly line of immaculate masonry that runs fastidiously along the cliff edge: Hadrian’s Wall.

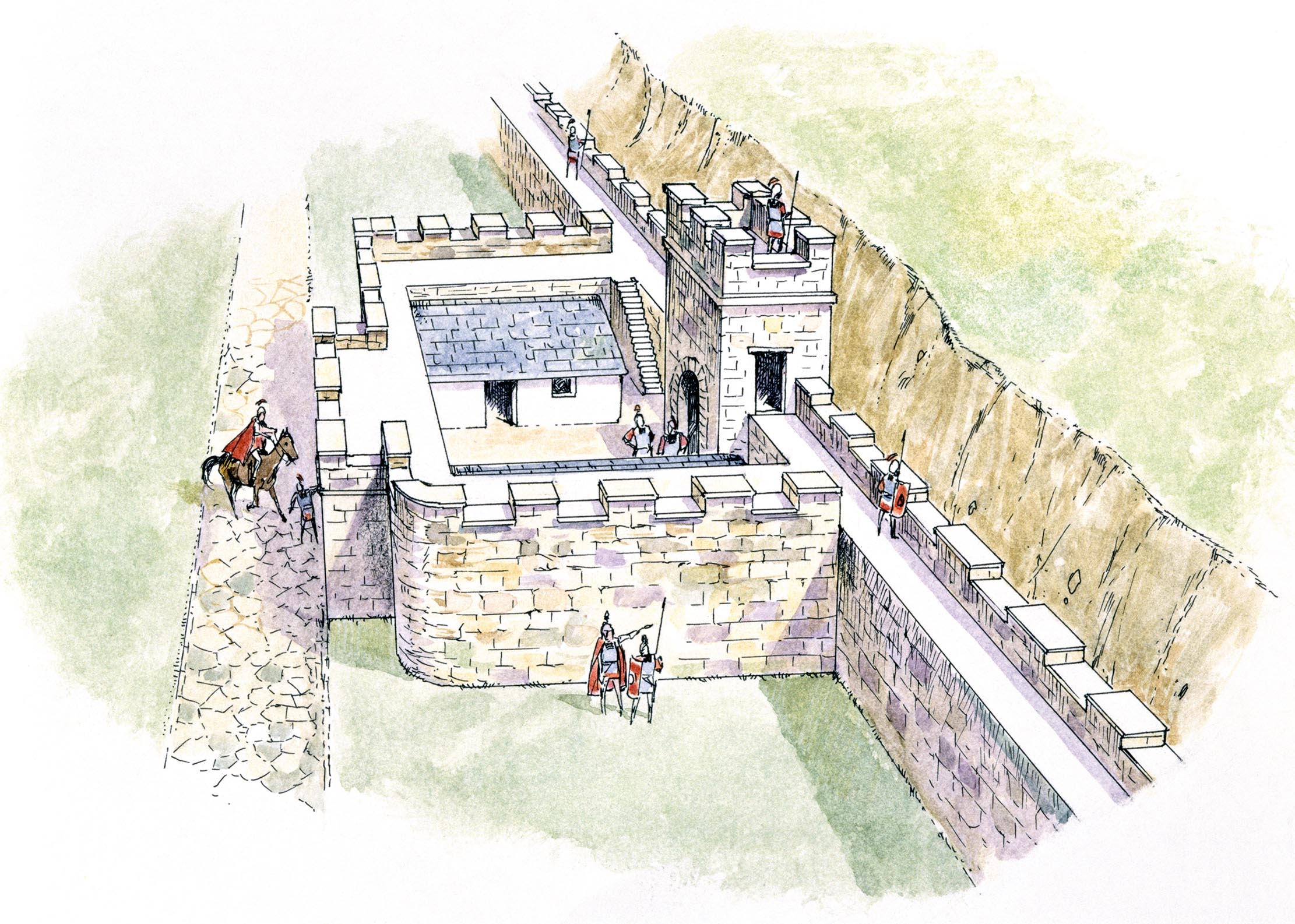

This breathtaking piece of engineering was begun 1,900 years ago, in AD122. It would stretch across the narrowest point in Britain, 73 miles from the mouth of the River Tyne to the Solway Firth, stand 15ft high and 10ft across, incorporate 16 forts, 80 milecastles and 240 watchtowers, as well as dozens of bridges, and be flanked by ditches and earthworks.

Hadrian's wall timeline

- AD122 Emperor Hadrian visits Britain. Construction of the wall — possibly to a plan he had devised — begins

- 140–158: The newly constructed Antonine Wall becomes the northern frontier of Roman Britain. Hadrian’s Wall is abandoned

- 160: The Antonine Wall proves impossible to defend. Hadrian’s Wall is re-garrisoned and becomes the northern boundary of the empire again

- 180 Major incursions by northern tribes lead to structural changes to the wall, including the narrowing of the northern gates of milecastles

- 208–211: Emperor Septimius Severus campaigns in northern Britain and organises major repairs to the wall

- 306: Constantine declared Emperor in York. He creates the position of Dux Britan-niarum, overall general of the northern frontier, in charge of the wall

- 410: Romans withdraw their armed forces from Britain

It took the 15,000 men of the 2nd, 6th and 20th legions six years to complete and used an estimated two million cubic yards of stone, all of it cut with hammers and chisels. Stand by the foaming waters of the North Tyne, near the remains of the fortified bridge that once spanned the river near Chollerford in Northumberland, or walk the line of the wall as it plunges into the verdant coil of the Irthing Gorge near Birdoswald in Cumbria before hauling itself up the far side to Willowford Farm, and you will see the magnitude of the task these legionaries faced.

Given the primitive nature of the tools and transport, the inhospitable landscape and the ferocious interventions of the local Celtic tribes, building the wall was a feat that makes constructing Crossrail look like assembling a flat-pack bookcase. As William Hutton, a game 76 year old who walked the length of the wall in 1801, noted: ‘Men have been deified for trifles compared with this admirable structure.’

Why Emperor Hadrian determined on such a course is hard to say. Whether the wall was built to divide the fearsome Brigantes of the Pennines from their kin to the north, to protect against invasion from the unknown lands of Scotia (which, for all the Romans knew, could have been as large as Asia) or simply to keep the legions out of mischief during a time of relative peace cannot be established with certainty. But, regardless of its practical aims, the wall was a masterful piece of imperial propaganda. No barbarian could look at it and fail to be impressed.

Since 1987, Hadrian’s Wall has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but it was not always so carefully preserved. Until late-Victorian times, stone from the wall and its buildings was routinely pilfered, the property of anyone on whose land it stood. Whole sections were dismantled and the beautifully dressed stonework of the legionary masons refashioned into farmhouses, churches and barns. In Tudor times, Lord Dacre dismantled an entire fort at Drumburgh in Cumbria and used it to make a ‘pretty pyle’ of a castle for himself. The worst damage was done in 1746, when Gen George Wade, in a hurry to move his army from Newcastle to Dumfriesshire after the Jacobite Rebellion, used the Roman Wall for the hard core of his Military Road.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Thanks to these ravages, Emperor Hadrian’s great barrier is now rarely more than 6ft high and often much lower than that. What once kept out hordes of bloodthirsty warriors is, these days, barely proof against the most timid of sheep. Yet, if the wall is now low on stature, it remains high on atmosphere. Spend 15 minutes in the soggy trough of land around the Brocolitia temple, where soldiers from Spain, Syria and Belgium once made sacrifices to a Persian deity, the purple mass of the Pennines looming to the south, dark clouds massing above, and even the most cynical begin to wonder about the power of pagan gods.

Hadrian's Wall trivia

- Evidence suggests that the wall may originally have been painted white.

- Sycamore Gap features in the Kevin Costner film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, in a sequence in which the hero walks from the White Cliffs of Dover to Nottingham — quite a detour.

- The wall was built to a strict military plan that didn’t allow for variation. As a result, some of the mile castles are built on 20% slopes and one has a northern gateway that opens over a sheer drop.

- In 1929, Housesteads fort was put up for auction at a land sale, but bidding failed to reach the reserve price.

- People often say ‘north of Hadrian’s Wall’ to mean Scotland, but the Roman wall is not—and never has been—the border between England and its neighbouring country.

- The Wall that protects the Seven Kingdoms in A Game of Thrones was inspired by author George R. R. Martin’s visit to Hadrian’s Wall in 1981.

How to visit Hadrian's Wall

The wall is free to see and visit all the way along, and you can even walk the length of Hadrian's Wall if you've a week or so to spare — there are itinerarites and details of visitor centres at hadrianswallcountry.co.uk. The major Roman remains along the way — most notably Housesteads Fort, one of the best-preserved Roman sites in Britain — are run by English Heritage; entrance fees apply for non-members.

The route of Hadrian's Wall

If starting on the west coast, Hadrian's Wall begins at Bowness-on-Solway, a village in one of England’s unfairly forgotten corners, where rusting metal signs lean at drunken angles and egrets stalk the brackish waters of the great firth. Beyond the excavated ruins of the Maia Fort and the odd bump and lump, there’s not much of the wall to see here. In the urban sprawls of Carlisle and Newcastle, too, Hadrian’s great endeavour is all but invisible, occasionally popping up near roundabouts or on the fringes of light industrial estates. It really asserts itself in the section between the King Water, east of Walton in Cumbria, and the A68 — once the Roman road of Dere Street — in Northumberland.

The journey from the west takes you into the lush valley of the Irthing, where deciduous woodland surrounds Naworth Castle and shades the path, and past the stone arches of Lanercost Priory — part-built with Roman stone — where a sign warns motorists that cattle may eat their wing mirrors. A steep incline leads up to the village of Banks, once home to the painters Ben and Winifred Nicholson. From a neat, square Roman signal tower near the couple’s farmhouse, you can admire a sweeping southerly view — straight ahead, the aptly named Cold Fell, to the right, the sharp peaks of Helvellyn and Skiddaw.

Further on is the Roman fort of Birdoswald and beyond it the former spa town of Gilsland, where Sir Walter Scott proposed to his wife, Charlotte. Past Gilsland, you see for the first time the rugged igneous rocks of the Whin Sill rising up suddenly from beyond the banks of the Tipalt Burn. The legion construction gangs must have seen this view. Tough and stoic they may have been, but the sight would surely have made them curse and groan almost as much as it does the modern-day walker.

The grumbling would have continued as they laboured up the steep bank outside what is now the village of Greenhead and onto an exposed highland that carries on for 35 craggy, ankle-jarring miles. The route takes you to Sewingshields (where some believe King Arthur and his baptised Romano-British knights made a final stand against invading Saxons, Picts and Scots) and onward to Heavenfield and Stagshaw, with only the wooded valley of the North Tyne for respite (that the Roman commander’s house at Chesters had underfloor heating is unsurprising), before beginning the slow descent into what is now Newcastle.

There are picture-postcard views along this section — the glimmering waters of Crag Lough through a narrow copse of beeches, the oft-photographed ‘nick’ of Sycamore Gap — but it seems unlikely the legionaries paused long enough to appreciate them. When they’d finished the job, they headed back to their bases in York and Chester. They were far too important for patrol and garrison duties; instead, the forts they’d built were filled with auxiliaries from all across the empire.

The soldiers left behind small fragments that give a human touch to the ruins. Many are dedications to officers or gods — or simply declarations of artisan pride. ‘The first cohort of Dacians’, reads an inscription at Birdoswald, ‘restored the commandant’s house which had fallen into ruin.’ Others are quirkier or more personal. On Stagshaw Bank, north of Corbridge, a stone commemorates a soldier killed by lightning; at a quarry near Brampton, soldiers carved a caricature of their commanding officer, together with a rude symbol.

At Vindolanda, a civilian settlement to the south of Housesteads, on the Stanegate (once the service road for the wall), wax writing tablets have been found preserved in peat. The letters inscribed on them are full of the mundane details of life in the town 1,900 years ago. At times, it seems not so very far removed from our own. The writers tell of meals they have enjoyed, send birthday greetings, moan that the addressee does not respond often enough or obsequiously seek advancement from superiors.

One letter to a soldier clearly accompanied a parcel: ‘I have sent you pairs of socks from Sattua, two pairs of sandals and two pairs of underpants,’ it reads. Patrolling the perimeter at Walltown with a December gale gnashing, the sky as dark as a bruise and the scent of snow in the air, the recipient must have been very glad of those socks.

Walking Hadrian's Wall: An epic walk from coast to coast and back in time

One of Britain’s most famous landmarks makes for an epic walk back in time – and it's a journey that

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

How farming can change to feed us all while saving the planet — and no, you absolutely won't have to become vegan

Organic farmer Patrick Holden is an early adopter of mixed farming systems, where livestock and crops work together hand-in-hand. He

Guide to Northumberland’s famous footballing brothers, many castles, oh and a certain famous wall

Rutland is the only county in England without a McDonald’s, plus other things to celebrate

Harry Pearson is a journalist and author who has twice won the MCC/Cricket Society Book of the Year Prize and has been runner-up for both the William Hill Sports Book of the Year and Thomas Cook/Daily Telegraph Travel Book of the Year.

-

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025Mondays's quiz tests your knowledge on English kings, astronomy and fashion.

By James Fisher Published

-

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'A party barn is the ultimate good-time utopia, devoid of the toil of a home gym or the practicalities of a home office. Modern efforts are a world away from the draughty, hay-bales-and-a-hi-fi set-up of yesteryear.

By Annabel Dixon Published

-

10 of the best beaches in Britain and Ireland, from sandy spaces for families to places of exquisite natural beauty

10 of the best beaches in Britain and Ireland, from sandy spaces for families to places of exquisite natural beautyIf you're planning a holiday in Britain or Ireland this summer, you're in for a treat: the spectacular coastlines of these countries get battered by weather in autumn and winter, but on a fine day in spring or summer they're the equal of anything in the world. Rosie Paterson picks out 10 of the very best, and suggests places to stay near each once tourism is back up and running.

By Rosie Paterson Published

-

Petworth: What to do, where to stay and what to eat in one of Sussex's most charming towns

Petworth: What to do, where to stay and what to eat in one of Sussex's most charming townsMelanie Bryan spent a weekend in Petworth, the picture-perfect market town in the South Downs that boasts superb shopping, food and one of Britain's greatest country houses.

By Melanie Bryan Published

-

Britain's most beautiful narrow-gauge railways, from Norfolk to Wales

Britain's most beautiful narrow-gauge railways, from Norfolk to WalesChris Arnot names the five British railways that every train lover should have on their bucket list.

By Country Life Published

-

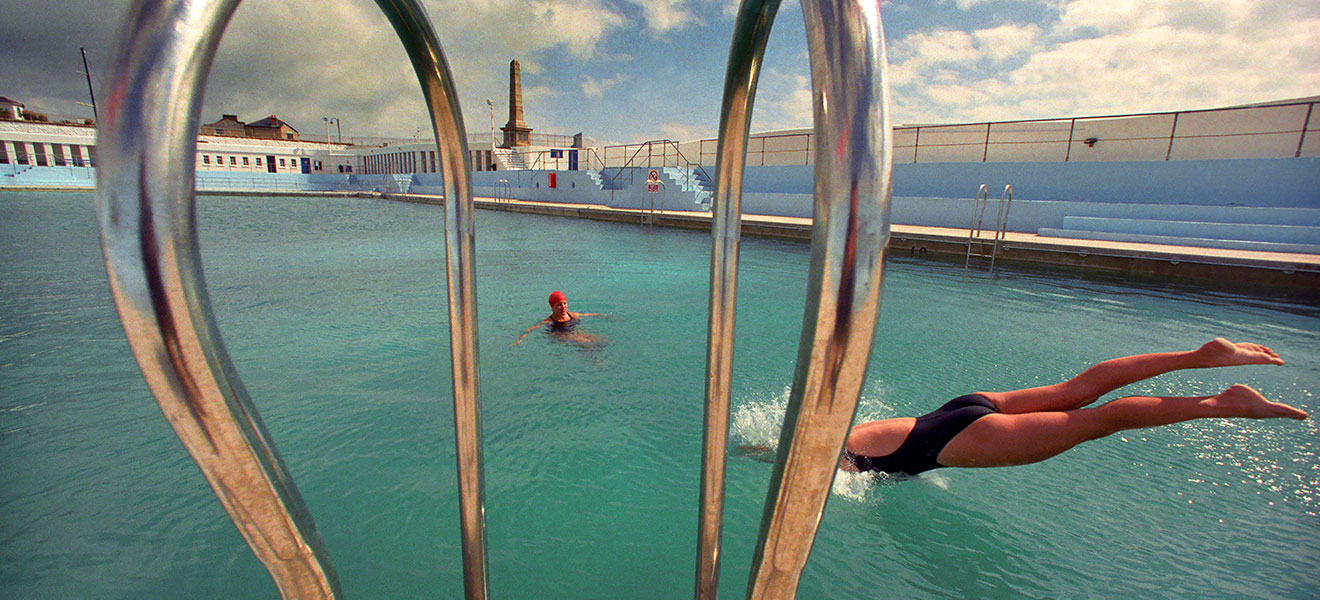

The original Art Deco lido that'll soon be as warm as a bathtub, thanks to Icelandic-style geothermal energy

The original Art Deco lido that'll soon be as warm as a bathtub, thanks to Icelandic-style geothermal energyAn Art Deco lido in Penzance will soon boast bath-temperature waters thanks to new technology that uses heat tapped from within the Earth. Julie Harding reports.

By Country Life Published

-

Birdsong Barn: A holiday cottage getaway set in its own private nature reserve

Birdsong Barn: A holiday cottage getaway set in its own private nature reserveBirdsong Barn, in the heart of England's '1066 Country', offers a unique break: a beautifully-converted building with a private 350-acre nature reserve on its doorstep. Toby Keel paid a visit.

By Toby Keel Published