Beyond Stonehenge: The lesser-known stone circles of Britain

More likely to be ovals, arcs or ellipses, the origins and purposes of our myriad mysterious and sacred stone circles are still up for debate, says Ruth Bloomfield.

As the evenings grow lighter, the countdown to the summer solstice gets under way. For countless generations, the longest day of the year has been a cause of celebration, which has inspired some of the most astonishing, evocative and mysterious manmade wonders of the world in the shape of stone circles.

Author and enthusiast Robin Heath fell under the spell of these features as a child on long hikes through the Peak District with his father, when taking in views of beguilingly named sites such as Arbor Low and the Nine Ladies.

‘I was fascinated,’ he admits. ‘As a child, I was in awe of them and I still am. They provide a sense of sanctuary, of being in a sacred space, in the same way a cathedral does.’

He asked lots of questions, which his father couldn’t always answer.

‘When you are an eight-year-old lad and your dad doesn’t know something, it is quite a big deal, so I decided to find out the answers for myself.’

In fact, Mr Heath Snr was far from alone in his lack of comprehensive knowledge. Most British stone circles are 4,000 to 5,000 years old and divining their origins and purpose has long been a matter of conjecture and debate.

For a start, the term ‘stone circles’ is simply a useful shorthand. Many of the ‘circles’ are actually ovals, arcs and ellipses.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It isn’t even clear how many there are in the UK (nobody has comprehensively catalogued them), but it’s likely to be more than you thought.

Estimates range from about 800 to 1,300, with Mr Heath believing there are about 400 ‘worth visiting’, out of a total of about 1,000.

Richard Bradley — one of Britain’s foremost experts on prehistoric archaeology — recommends a trip to the Outer Hebrides to see one of our earliest circles, thought to be some 5,000 years old.

On the west coast of Lewis, the Callanish Stones stand between water and sky, with Loch Roag in front and the hills of Great Bernera behind.

The site comprises a main circle of 13 stones, with arcs of standing stones running off it and a monumental seven-ton, nearly 16ft central stone.

‘They do draw respect, simply because they are so visual,’ declares Prof Bradley, who teaches at the University of Reading. ‘They dominate the landscape.’

Local legend has it that the Callanish Stones are actually giants that were turned to stone after refusing to convert to Christianity.

Hundreds of miles away, in Stanton Drew, Somerset, stands another circle that is similarly immersed in folklore and legend. It is said these stones are the remains of a wedding party tricked, by the Devil, to dance on a Sunday.

‘People have always tried to make sense of the mystery of them,’ observes Prof Bradley. ‘The idea that they are petrified human figures is very persistent and some of them do look, in a way, like very abstract sculptures of the human form.’

Most experts agree stone circles have an astronomical purpose. In 1955, the British academic Alexander Thom theorised that they were observatories for stargazing.

In 2016, the Journal of Archaeological Science published a report confirming that standing stones in Scotland had been positioned to show the most extreme rising and setting points of the sun and the moon.

Getting to the bottom of this question is something Mr Heath has devoted himself to full-time since retiring in the mid 1990s.

Now 72, he has written more than 10 books on the subject. What fascinates him is the stones’ elaborate patterns and geometries.

He believes that the very precise siting of the stones with equal distances between them, in perfectly formed geometric shapes, cannot be an accident.

‘These were primitive people, but they clearly understood geometry,’ he muses. ‘The distances are not random. I think that people were trying to bring the heavens to earth, trying to understand the patterns of the seasons and time. Of course, I can’t be sure. These are things that keep me awake at night.’

One fact he is sure of, however, is that huge amounts of energy were expended building circles.

At Long Meg and Her Daughters, a 350ft-diameter circle near Little Salkeld, Cumbria, the largest stones are estimated to weigh 8½ tons each.

‘They were definitely not built on a whim on a Sunday afternoon,’ laughs Mr Heath.

Technologically, Win Scutt, properties’ curator for English Heritage’s western region, is confident Neolithic man was easily advanced enough to manage the transportation of vast hunks of rock over rough land- scape, often for considerable distances.

‘They were sophisticated carpenters and constructors, they built causeways across marshland and large buildings,’ he attests.

‘There are various ideas around that they used levers to lift the stones onto rollers, which were then pulled along either by men or by small oxen. Then, all you would need was an A-frame to pull the stone upright.’

Some believe stone circles served as temples; others see them as arenas for ceremonies, celebrations and feasts.

There is evidence they have been used for cremations, as well as for legal proceedings or even as marketplaces. Perhaps the truth is they were the focus for a combination of events, evolving over time.

‘In the past 300 to 400 years, we have separated these functions,’ explains Mr Scutt. ‘I think that, when you go back to prehistory, it was probably much more intertwined.’

He points out that many circles are surrounded by a large henge or deep ditch resembling an amphitheatre.

‘People could sit on the bank and look across to the flat space in the middle.’ He is also certain that the idea that druids built our stone circles is a red herring.

‘The timeline is simply wrong. The earliest mentions of these strange Celtic priests come in the 3rd century,’ he contends. ‘Stone circles have nothing to do with druids, full stop.’

Mr Scutt’s advice for those interested in stone circles is simply to visit them and to drink in the atmosphere. His personal favourite is Castlerigg, near Keswick, largely thanks to its Lake District backdrop.

Set on a small plateau and ringed by Cumbrian mountains, the circle of 40 stones was built in about 3,200BC.

The popular Victorian Gothic novelist Ann Radcliffe, who had a fondness for the supernatural, described Castlerigg as a place of ‘profound solitude, greatness and awful wildness’.

‘It is absolutely awe-inspiring,’ concurs Mr Scutt.

What you need to know about stone circles

- Stone circles are found on every continent. In Britain, most date from between about 3,000BC and 2,000BC. However, at Gobekli Tepe, in Anatolia, Turkey, there are circles built in about 9,000BC, making them more than twice as old as the pyramids

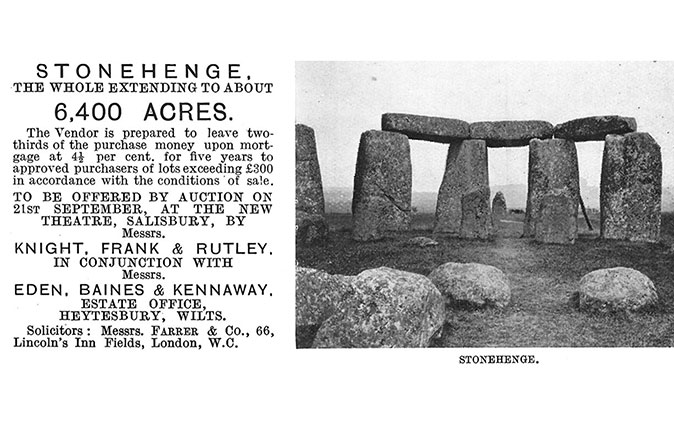

- Stonehenge began its life as a circular ditch and bank (known as a henge), dug in about 2,900BC. The first stones arrived in about 2,400BC and the site was rearranged several times over the next several hundred years

- Avebury , Wiltshire, is the largest stone circle in the world, with a diameter of more than 1,000ft

- Stone circles are often close to burial sites. Half a mile from The Hurlers, a trio of circles on Bodmin Moor, Cornwall, said to be the remains of men caught playing hurling on a Sunday, 19th-century treasure hunters excavated a barrow containing the Bronze Age gold Rillaton Cup. The cup, which is now on display in the British Museum, found its way into the royal household where, legend has it, it was used to store the collar studs of George V

- A popular attraction since the Victorian era, about 1.6 million people flock to Stonehenge (below left) in a normal year. The novelist Henry James was so moved by his visit that he wrote: ‘There is something in Stonehenge almost reassuring; and if you are disposed to feel that life is rather a superficial matter, and that we soon get to the bottom of things, the immemorial gray pillars may serve to remind you of the enormous background of time’

- Not all stone circles are quite what they seem. In 2018, archaeologists were alerted to the presence of an undiscovered, ancient stone circle on farmland in Leochel-Cushnie in Aberdeenshire. They thought they had a major discovery on their hands — until the farm’s former owner confessed he had built the circle as a folly in the 1990s

Jason Goodwin: 'What gets lost will be forever lost, whereas pylons, cars and trains may be rendered obsolete'

Jason Goodwin muses on economics, Stonehenge and social media.

Credit: ©Country Life Picture Library

The day that Stonehenge was sold via the pages of Country Life

Stonehenge is shortly to be changed forever, with the planned tunnel getting the go-ahead. But it's not the first time

Should we re-roof Tintern Abbey, and re-erect the fallen stones of Stonehenge?

Our most celebrated ancient ruins draw visitors by the tens of thousands, drawn by the mix of history, romance and

Credit: Rex

Celebrating 100 years since Cecil Chubb donated Stonehenge to the nation

Friday 26 October 2018 marks the centenary of Cecil Chubb's magnanimous gesture: turning Stonehenge over to the care of the

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Country Life 23 April 2025

Country Life 23 April 2025Country Life 23 April 2025 looks at how to make the most of The Season in Britain: where to go, what to eat, who to look out for and much more.

By Toby Keel

-

The big reveal: A first look at Country Life's RHS Chelsea Flower Show stand

The big reveal: A first look at Country Life's RHS Chelsea Flower Show standInterior designer Isabella Worsley reveals her plans for Country Life’s ‘outdoor drawing room’ at this year’s RHS Chelsea Flower Show.

By Country Life