Curious Questions: Why did the Victorians become so obsessed with travelling the world?

On the 150th anniversary of the death of British explorer David Livingstone, Ben Lerwill asks why intrepid British men and women have long been–and still are–fond of venturing to the farthest corners of the globe.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the early 1820s, a 10-year-old boy was put to work in a cotton mill on the banks of the River Clyde. He was tasked with tying together threads of broken yarn on a factory floor that thundered with the din of spinning machines. It was the sort of tough, monotonous environment that gets young minds dreaming of escape, which might help to explain why the boy would go on to become one of Britain’s best-known overseas explorers.

It’s now 150 years since David Livingstone died — on May 1, 1873 — near the headwaters of the Congo. His earlier disappearance and his meeting with reporter Henry Morton Stanley (‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’) have been documented untold times. He is remembered these days as a single-minded missionary, but equally as someone with the gumption to journey into far-flung territory simply because it was there. He became the first European to make an authenticated crossing of the African continent. Bet that surprised them back at the mill.

Looking at Livingstone and his exploits prompts the question: what is an explorer? Is it a pioneer, a serious and purposeful wayfarer who sets off with ambitions to serve humankind for the better? Is it a colonial throwback to ‘discovering’ distant lands?

Is it an adventurer, a wide-eyed rover setting off to the back of beyond in search of new experiences? Is it Capt Cook? Freya Stark? A real-life Phileas Fogg? The answer, in broad terms, is that anyone with one eye on an atlas and the other on the horizon has historically fitted the description. However, their motivations varied. Several British explorers had dreams of professional success, wealth or prestige and many of their journeys now have jarring colonial overtones — some can be unedifying, even shameful, to modern eyes. For many other people, however, it was the thrill of fresh escapades that compelled them to venture out to the most remote corners of the globe — and still does today.

‘I’ve often wondered where the urge to explore comes from,’ muses expedition leader and wilderness guide Megan Hine, recently back from skiing more than 300 miles across Arctic Sweden (‘the snow was thigh-deep in places’) and currently preparing to lead a trip to Outer Mongolia (www.meganhine.com). ‘It’s such an inherent part of who we are as human beings. If you watch young children, they’re constantly pushing boundaries and exploring the world around them. But exploration is also about understanding our own mental landscapes and crossing frontiers within ourselves.’

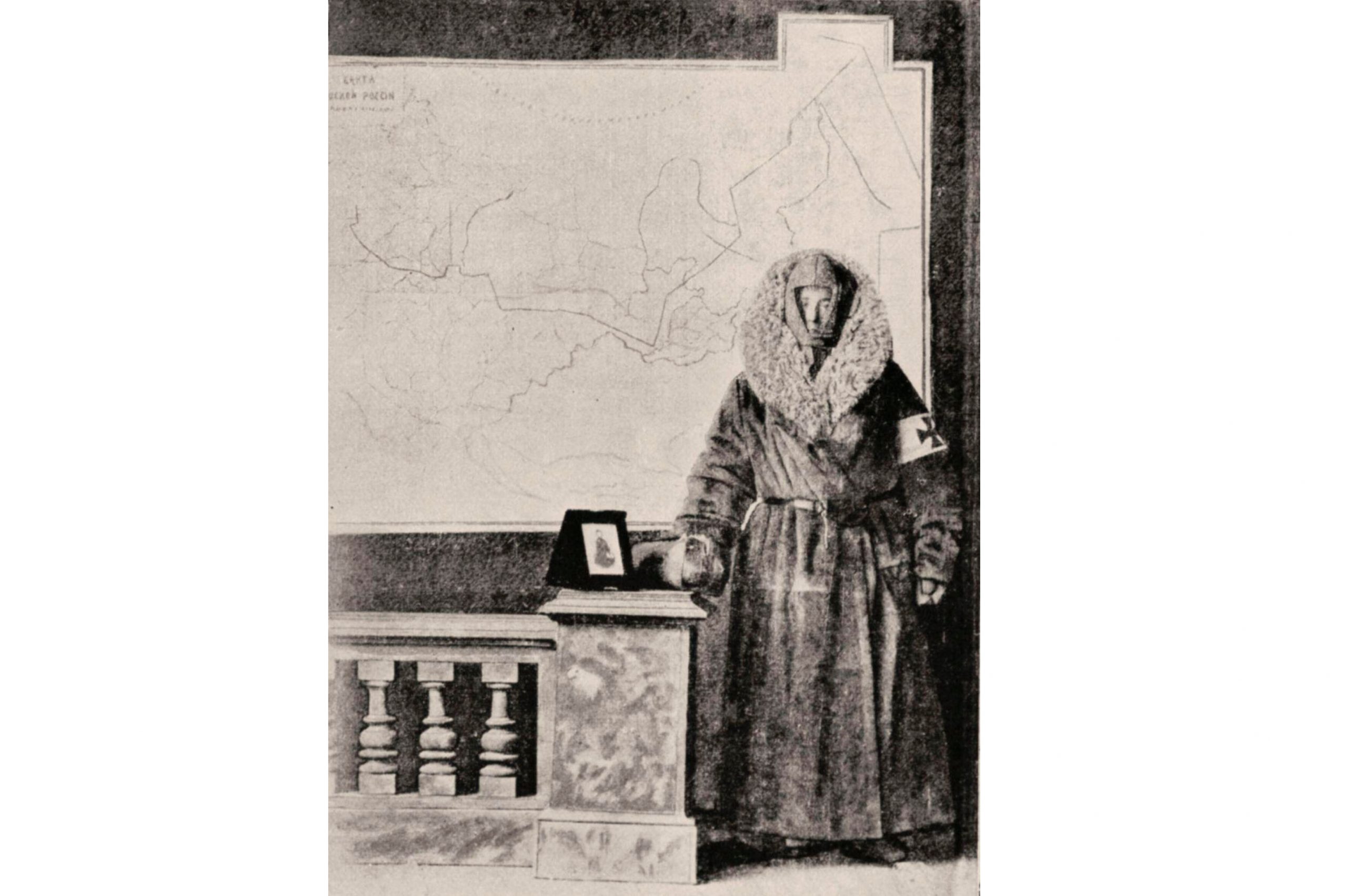

An air of storybook drama still lingers around many pre-war explorers. The cast list of sepia-tinted British globetrotters is crowded, varied and at times eccentric. To pick a mere handful from a list of hundreds, Frederick Marshman Bailey had passions that ranged from dining at The Ritz to butterfly-collecting in Tibet; Kate Marsden journeyed to Siberia in the 1890s ‘on sledge and horseback’ in search of a cure for leprosy; Francis Masson was compelled to collect new plant species, leading to him being imprisoned by the French in the Caribbean; and Charles Waterton wrestled a caiman in the rainforests of Guyana, then commissioned a painting to honour the feat (‘In a league of their own’, January 25).

Another restless character, George Ruxton, whose early-19th-century exploits took him everywhere from Central Africa to the Rockies, summed up a particular breed of Victorian-era explorer when he wrote: ‘I was a vagabond in all my propensities. Everything quiet or commonplace I detested and my spirit chafed within me to see the world and participate in scenes of novelty and danger.’ He died of dysentery in Missouri in 1848, aged only 27.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It’s worth highlighting that, even centuries ago, the idea of pushing endurance to the limits through travel was nothing new. Our species has always been inquisitive about what lies over the next mountain range, beyond the next forest, across the next sea. The Phoenicians, the Carthaginians and the Ancient Chinese were among those to undertake long and bold voyages into the unknown. ‘Why, then the world’s mine oyster,’ wrote Shakespeare. ‘Which I with sword will open.’ The resolve to seek and find tapped into something primal.

But exploration, of course, also needed money and equipment. It’s tempting to picture a latter-day explorer lighting a pipe after Sunday lunch and deciding the time is right for a jaunt to Timbuktu, but almost all large-scale expeditions of the past — and, indeed, the present — involved serious planning, a specific aim and major financial backing. Funding was perhaps more straightforward to come by in this country than in many other places.

‘Britain is unusually good at independent institutions developed in the public interest,’ says Joe Smith, director of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS, www.rgs.org), which was founded in 1830. The RGS helped support the monumental explorations of people such as Livingstone, Edmund Hillary, Ernest Shackleton and Robert Falcon Scott and is still very much going strong. Its overarching goal has always been to promote the advancement of geographical science.

‘We know exactly what we’re for, although the purpose behind our mission statement has entirely changed across time,’ says Prof Smith, reflecting on how much things have evolved since the Union Flag-draped days of the colonial era. ‘Today, all our knowledge is internationally networked. It’s collective. We’re equipped to support a very open-minded curiosity.’ He points out that the RGS still makes 60 or 70 project grants every year, mostly to younger researcher-explorers.

Being an island nation historically gave Britain not only a ready supply of people itching to witness and record the outside world, but the clout and infrastructure to allow them to travel. ‘We were helped by being a maritime economy early on and having that capability added to investment in geographical knowledge,’ notes Prof Smith. ‘But the derring-do of the moustachioed colonels looking to plant the flag — there’s no doubt there was national esteem and competitiveness involved there.’

No one could be further from a moustachioed colonel than the Turner twins, Hugo and Ross, who are both Fellows of the RGS and modern British explorers (www.theturner twins.co.uk). Hugo suffered a serious broken neck at the age of 17; a little more than five years later, in 2011, the brothers rowed across the Atlantic to raise money for charity Spinal Research. Their expeditions have since taken them to Mount Elbrus in Russia, the Australian outback, the Andes, which they crossed by bike (‘we pedalled 62 miles and climbed nearly 11,500ft on the first day alone,’ they recall), and the Greenland ice cap, where they conducted a modern-day test of Shackleton’s clothing and equipment from the Endurance mission (it coped remarkably well).

‘What makes an explorer? It’s that curiosity to learn something more, but it’s also a drive to make yourself a little less comfortable,’ says Ross Turner. ‘In the great era of explorers gone by, they lived in a world where travel wasn’t a product you could simply buy one day and be jetting off tomorrow. The idea of going off exploring still had a lot of mystery to it.’

Perhaps in the same way, he feels that contemporary explorers are often looking to avoid the trappings of convenience culture. ‘These days, if you live in London or a big Western city and you decide you want something, within half an hour you can probably get it. It’s very much a “Netflix-and-chill” world. That’s why some people are looking to step away from these environments.’

The twins use the idea of ‘travel with purpose’ as a motto for their own endeavours, aiming to expand understanding of geography, technology, science, human performance and history. ‘We like looking at things and questioning them,’ explains Hugo. ‘But exploration, however you define it, is your own discovery, your own journey. It doesn’t have to involve going thousands of miles away.’

Livingstone was mauled by a lion during his early wanderings through Africa, in 1844, yet spent much of the next three decades journeying through the same continent. This unflinching self-belief was one of the traits that once defined an explorer in the classic sense. Does the same refusal to be cowed by setbacks apply today?

‘There are still people doing exceptionally brave and difficult things,’ points out Prof Smith. ‘What I think really marks out the difference between explorers of the past and those of today is that a 19th-century explorer almost certainly had a military background and was probably trying to appear to have done it alone. Today, a really ambitious expedition usually involves a team approach and is much more likely to attend to the experiences, knowledge and context of the people living in the place you’re exploring. But the unifying things are these amazing human qualities of curiosity and sheer determination, and a bit of wit about overcoming obstacles.’ Here’s to another 150 years of exploration.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Caravaggio’s Eden: Why following in the footsteps of the artist is the ideal way to explore Rome

Mark Hedges dons his best walking shoes for a Caravaggio-themed walking tour of the Eternal City.

Five top tips to make the most of your dog walk, plus five incredible National Trust spots to explore off-lead

Credit: Cookson Adventures

Bucket list inspiration: A trip to the bottom of the ocean to see RMS Titanic while sipping a 1907 Heidsieck Gout Champagne

Cookson Adventures pride themselves on exploring what others deem impossible to explore. Their latest offering is no different; a voyage

Life on Shetland: The peace and security of an island existence

Eleanor Doughty explores life on Scotland’s myriad beautiful islands.

Ben Lerwill is a multi-award-winning travel writer based in Oxford. He has written for publications and websites including national newspapers, Rough Guides, National Geographic Traveller, and many more. His children's books include Wildlives (Nosy Crow, 2019) and Climate Rebels and Wild Cities (both Puffin, 2020).