Why is most new-build housing in Britain is awful — and why it doesn't have to be this way

Housing development is conditioned by concerns that have nothing to do with creating attractive or sustainable places to live. Clive Aslet gives his take on the situation, and suggests what we might be able to do about it.

Why is most new housing in Britain so awful? To some people, this will seem a highly prejudiced question, implying that development is necessarily a bad thing. They may even claim that it ignores the manifest unfairness of a society in which the older generation owns large houses and youngsters can't afford anything.

Yet to ignore the low aesthetic quality of most house building simply exacerbates the problem. A recent survey showed that two-thirds of the population would never buy a new home. That's surely a devastating judgement, given the effort to get more new homes built.

Public animosity is one factor in Britain's woefully slow rate of delivering them. When local people fear that development will spoilt their surrounding, they oppose it. The tortuous nature of the planning creates delay and reduces supply.

Government attempts to speed up the process cause it to lose by-elections in the South-East. Clearly, the system would work more smoothly if new housing estates were liked.

What are the factors at work?

Short- termism

Let's start with the most fundamental: the Government, volume house builders and even local people operate on a timescale that is far too short to produce good results. A change in the planning guidance given to local authorities two years ago has increased the period for which they plan from five to 15 years, but some have yet to catch up — and even 15 years is inadequate. Only large schemes can deliver the infrastructure — shops, schools, GP's surgeries — that make a suburb self-sustaining.

Given that house builders are unlikely to deliver more than 100 houses a year, not least because the market won't absorb more, a development site executed over five years will necessarily be a housing estate. It will not add anything by way of amenity to the town or village to which it's attached; on the contrary; it will put an extra burden on roads, schools and GP's surgeries.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

When one housing estate is added to another, the size of the whole will grow, but without the necessary benefits of green spaces, infrastructure and much else. Short-term planning, in other words, results in the multiplication of toxic housing estates, which leech off existing town centres, encourage high-carbon lifestyles and provide little beyond dormitory accommodation.

It is easy to blame the planners and the house builders for this predicament, but local opinion is also an issue. Take Framlingham in Suffolk, one of England's most beautiful and historically interesting market towns; over the years, it has been exceptionally well cared for, so that the immediate vicinity of the market square is well-nigh perfect.

Eight years ago, the architect Mark Hoare, who lives nearby, sought to preserve the future of the town by preparing a plan that identified development sites not for the five-year window then in place, but 150 years. 'I was trying to be realistic and look at the likely rate of the town’s expansion, so we could prepare for it. If you plan ahead, you can get facilities such as drainage, ecological provision, landscaping and the routes that will encourage residents to walk or cycle to the town centre to reduce the pressure on parking.’

But Mr Hoare’s intelligent and imaginative scheme was rejected by an anti-development lobby that—in defiance of Government edicts and population growth—wanted Framlingham to stay just as it is. Or rather, was. Because several sites identified by Hoare as part of his plan have, indeed, been developed, but merely as housing estates, without any of the advantages that a coordinated plan would have given.

It is difficult to retrofit a housing estate with the infrastructure that ought to have come with forward planning; in 150 years, Framlingham may well have sprawled to the predicted size, but an opportunity will have been missed.

There are signs that the lesson is being heeded, to judge from the new draft of the National Planning Policy Framework on which consultation is taking place; it recommends a 30-year horizon for major schemes, such as new settlements. But why only major schemes? All planning should take a long view.

Land value

There is another concern driving the short-term outlook of much development. Volume house builders answer to shareholders who want an instant return on investment; they are, therefore, motivated to build, sell and move on to the next project. In addition, they may have paid highly for the land on which they are building because development sites, in our highly regulated system, are at a premium.

This leaves little to spend on architecture, not to mention sports fields, avenues and community buildings. But they can get away with poorly planned developments because, at a time of undersupply, almost anything that is built will sell, providing it is keenly priced.

Imagine, however, that the land was in the long-term ownership of people whose sole object was not to turn a quick profit for shareholders, but who had a commitment to how the place looked and worked for future generations.

Quality would improve and the ultimate return to the landowner would be bigger, because the initial investment in place-making is more than offset by the later rise in house values. As an added benefit, the initiative would be wrested from the handful of volume house builders that dominate the market and have traditionally had the ear of Government.

This may seem Utopian, but experience shows the contrary. Having master planned the Duchy of Cornwall’s new major developments of Tregunnel Hill and Nansledan, outside Newquay in Cornwall, Hugh Petter of Adam Architecture has now designed schemes for a number of landed estates, including Burghley and Blenheim: ‘A landowner can go into partnership with a regional non-Plc house builder, under a common aspiration contract. This means the landowner keeps control and has to sign off all the drawings and finished buildings.

'The public realm can be regulated by a covenant, which is popular with the existing community, because people know they’re getting something that’s going to look beautiful and will stay beautiful forever. Landowners then usually take a number of houses within the development and keep them as rental properties because they like the income stream to compensate for the loss of agriculture from the land.’

By talking to the parish council and community groups, to see what local needs are and sharing thoughts on design, landowners may be able to achieve the designation of a rural exception site, enabling a development where permission would not normally be given. Result: harmony in all senses.

This approach has become known as Landowner Legacy, but need not be confined to great estates; it could equally be open to farmers, local authorities, Government ministries or any other body with a long-term interest in the land. Over time, control could pass from the landowner to a community trust: Hampstead Garden Suburb would be a historical model to study.

The motor car

A generation ago, developments took a shape determined not by architects or urban planners, but by traffic engineers. Streets were designed to facilitate the movement of cars along gently curving lines with nothing to impede the driver’s line of sight. Incredibly, although the Georgian square is one of the glories of British cities, the rulebook made it impossible for new squares to be built, as the corner junctions were deemed too dangerous for cars.

Houses were arranged around cul-de-sacs, with turning circles at the bottom—a form that does nothing to encourage interaction between residents. Shops and railway stations could only be conveniently reached by car.

The example of Poundbury in Dorset threw all those car-centric ideas out of the window and showed that it was possible to design a settlement in which people could walk or cycle to school, shops and jobs. Cars aren’t kept on front drives or the street outside the house, ideally, but in parking areas tucked out of sight.

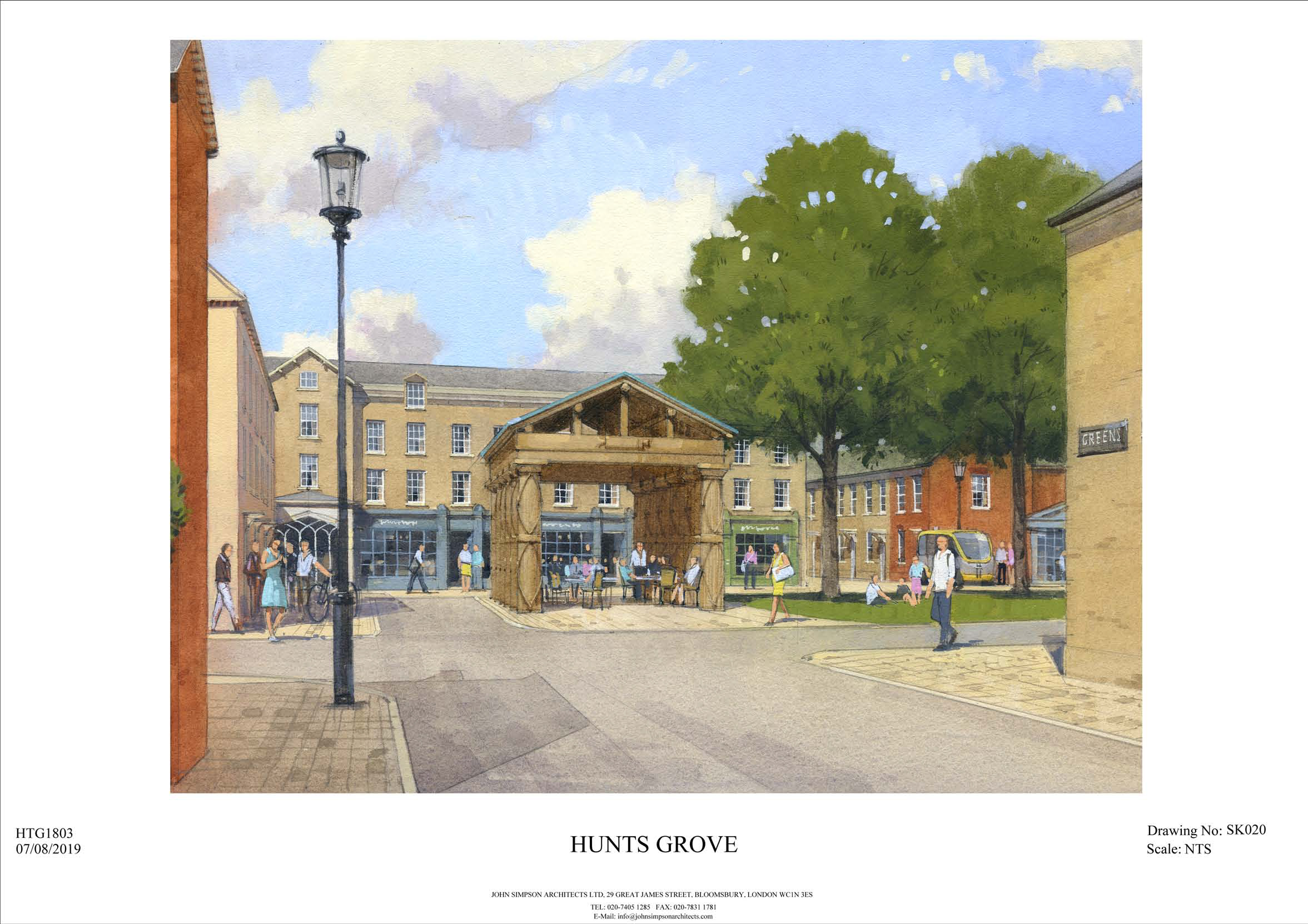

Unfortunately, many local-authority traffic engineers have not taken these insights to heart and still operate by the old rulebook. In fact, according to the architect John Simpson, they’re getting worse.

‘Highways authorities are becoming less and less cooperative and more intransigent in their application of highway criteria, making it more difficult to create genuinely urban spaces.’ Cars are now not only bigger than they used to be, but the rules over where they can be parked are more stringent. ‘In the case of one local authority, in a relatively rural location, they will not even consider garages as parking spaces. As a result, new streets are dominated by a sea of parked cars.'

Over-regulation

Generally, the best developments are those by small builders who are more responsive to local needs and can work on a more intimate scale. Volume house builders are prone to deliver a one-size-fits-all product, wherever they are in the country. They offer a large range of house types, but that is hardly helpful when they are inappropriate to the place in which they are built.

The poor results delivered by these big firms has led to regulations, intended to drive up standards, but it has had the unintended consequence of forcing smaller companies out of development altogether. As Mr Petter explains: ‘It used to be that, once builders got a commission, they could go to the bank to borrow against the planning consent to fund the discharge of the conditions.

Now, all the technical reports are required up front: noise, ground contamination, flooding and so on, all of which cost tens if not hundreds of thousands of pounds to produce. So the speculative cost is huge.’

Counter-intuitively, one of the Government’s responses to the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission’s report—first chaired by the late Sir Roger Scruton and subsequently co-chaired with Nicholas Boys-Smith—has been to seek to reduce regulation. This has led to accusations of introducing a developer’s charter: the opposite of what is intended—which shows how fraught the subject of house building has become.

Design

It could be argued that the design of individual houses in a development makes less of an impression on the eye than the pattern of the streets and the disposition of buildings along them. There is a premium on detached houses and they are, therefore, what developers try to provide; but old villages usually contain runs of terraces, a building type that is more economical in its use of land and more energy efficient.

Architects can find other means of grouping houses into blocks, which form more cohesive streetscapes, but volume house builders are reluctant to use architects.

Instead, they provide a large number of house types, which present a multiplicity of differences in detail, but, as the same offer is made across the whole country, take little account of traditional building methods. An improvement could be made by the Government mapping the vernacular styles across Britain, as is already done with landscape, and require that developers adapt their designs to the locality.

One problem is the sheer variety of models that buyers can choose from. ‘The street,’ says the architect Francis Terry, ‘becomes very noisy to look at. Really beautiful villages are all made from the same material—stone in the Cotswolds, red brick in Essex—and there’s a lot of repetition. The trouble with the volume house builders is that they mix red brick, yellow brick, render, slate and weatherboarding in the same development, in an effort to create instant history—but that doesn’t fool anyone.’

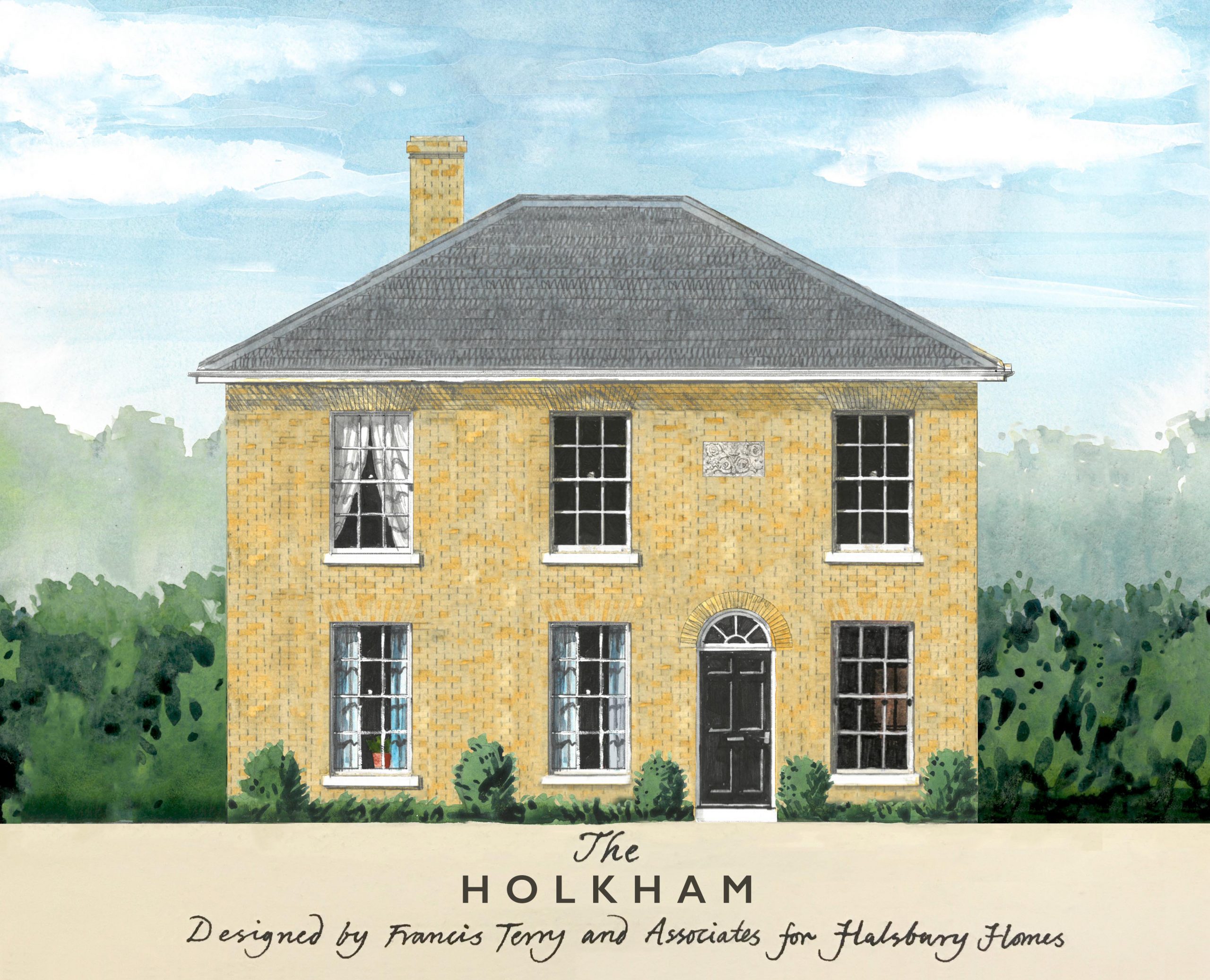

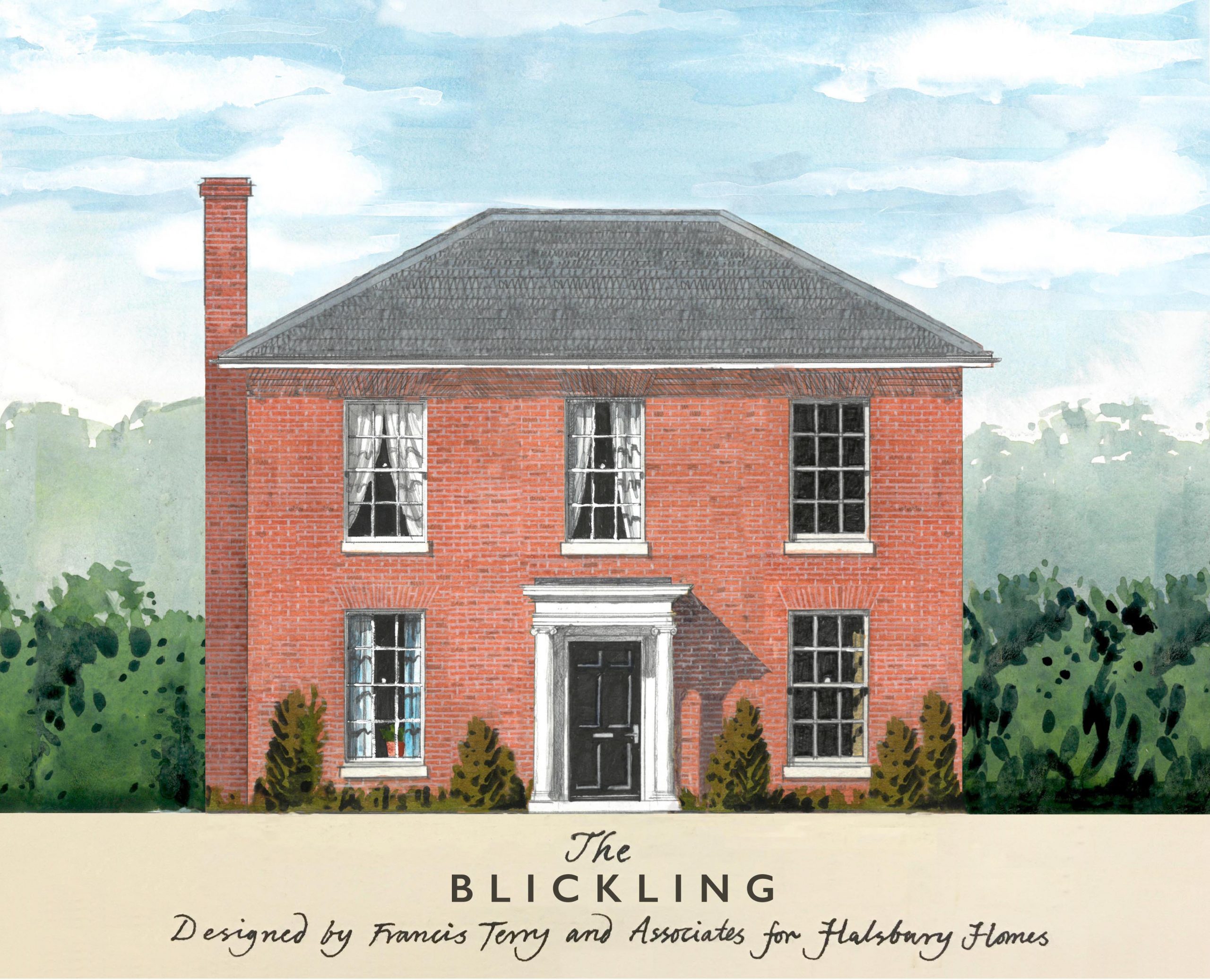

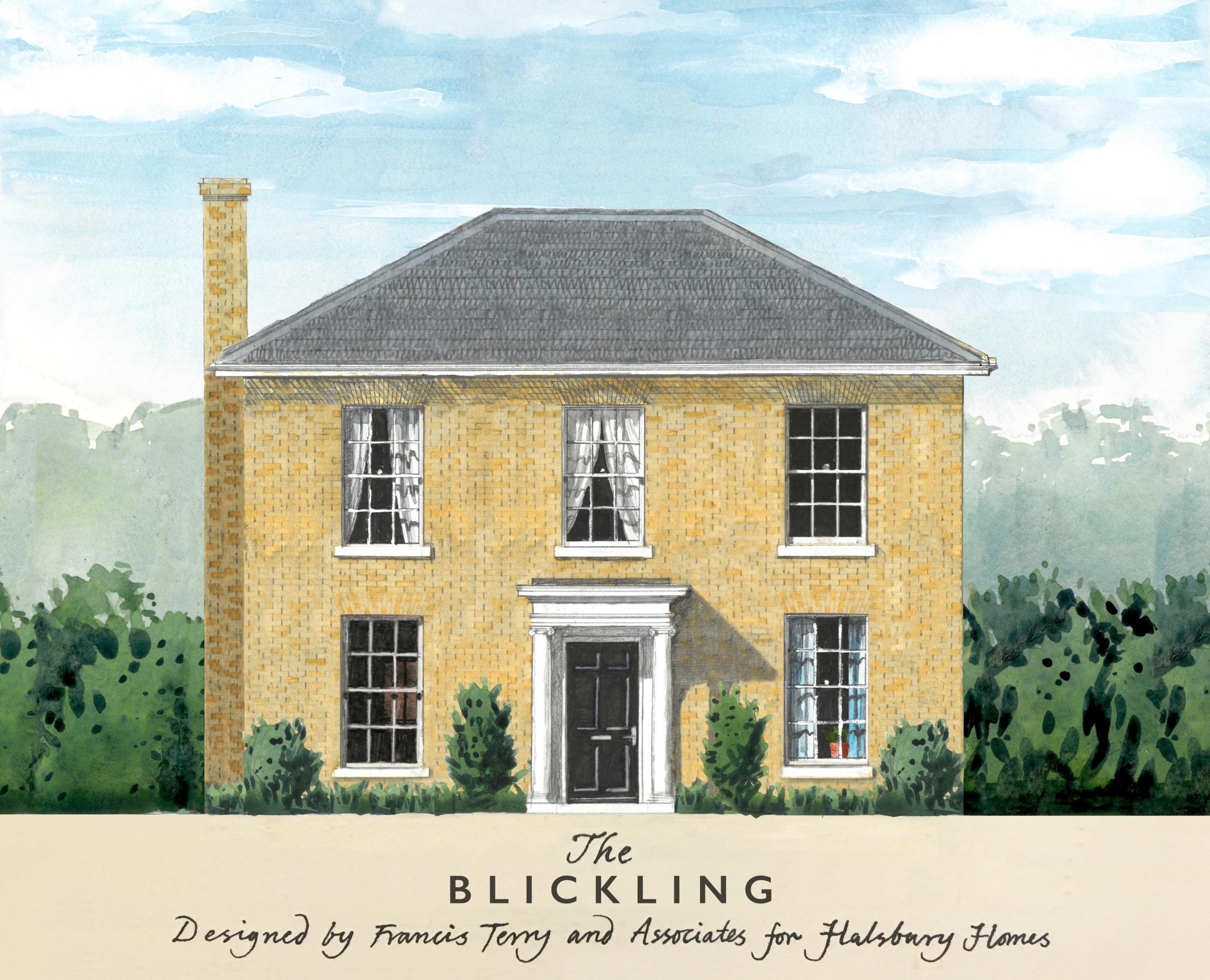

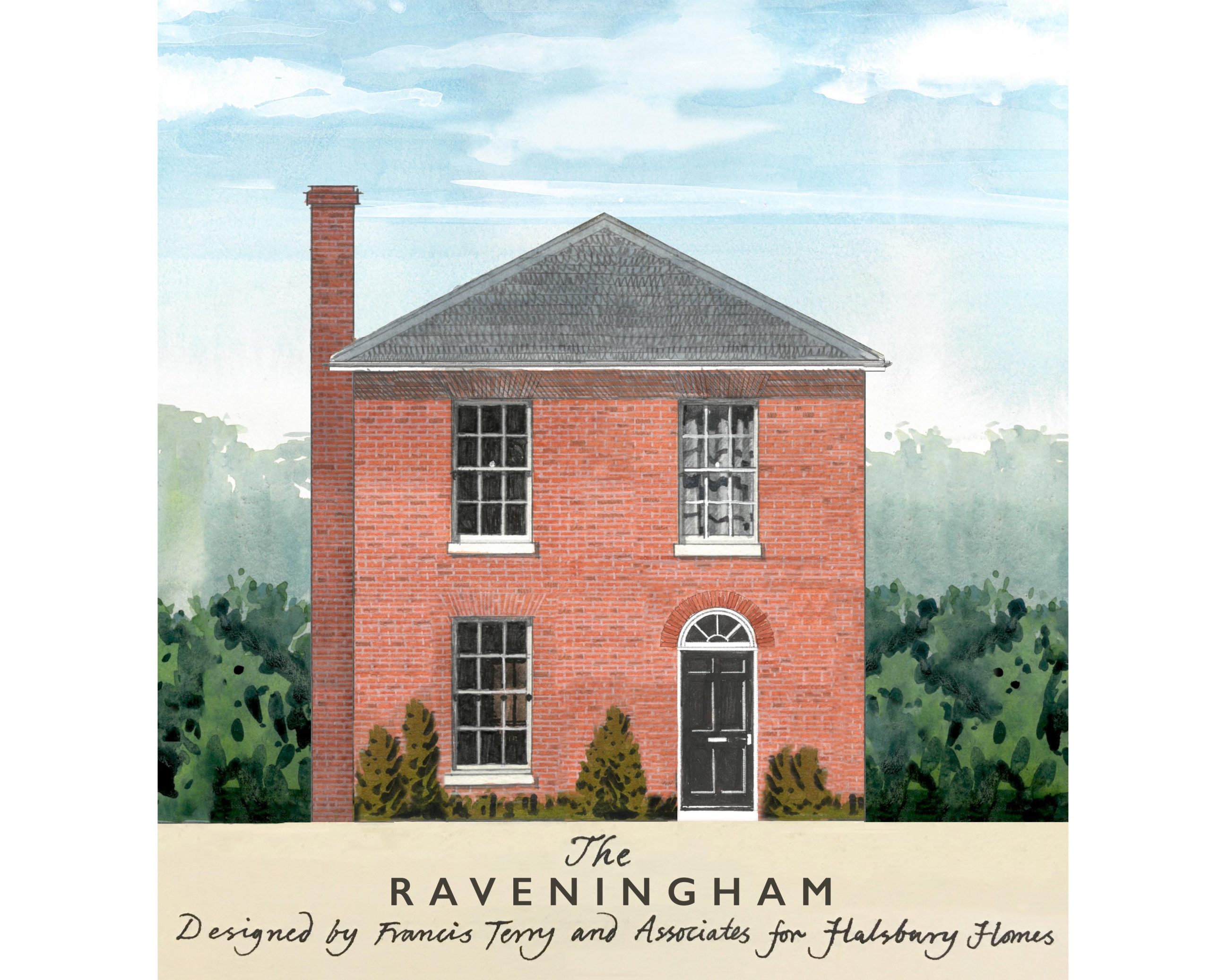

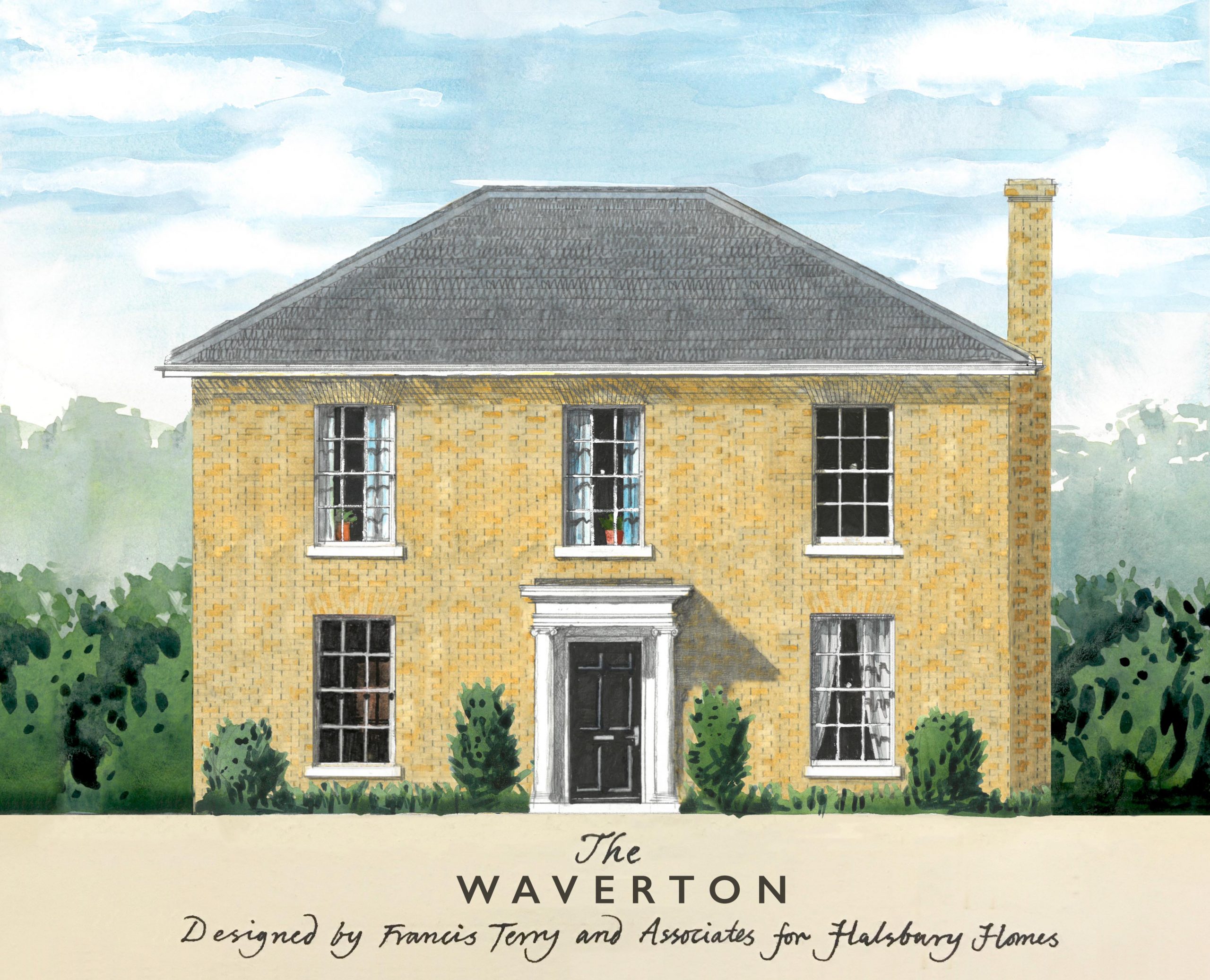

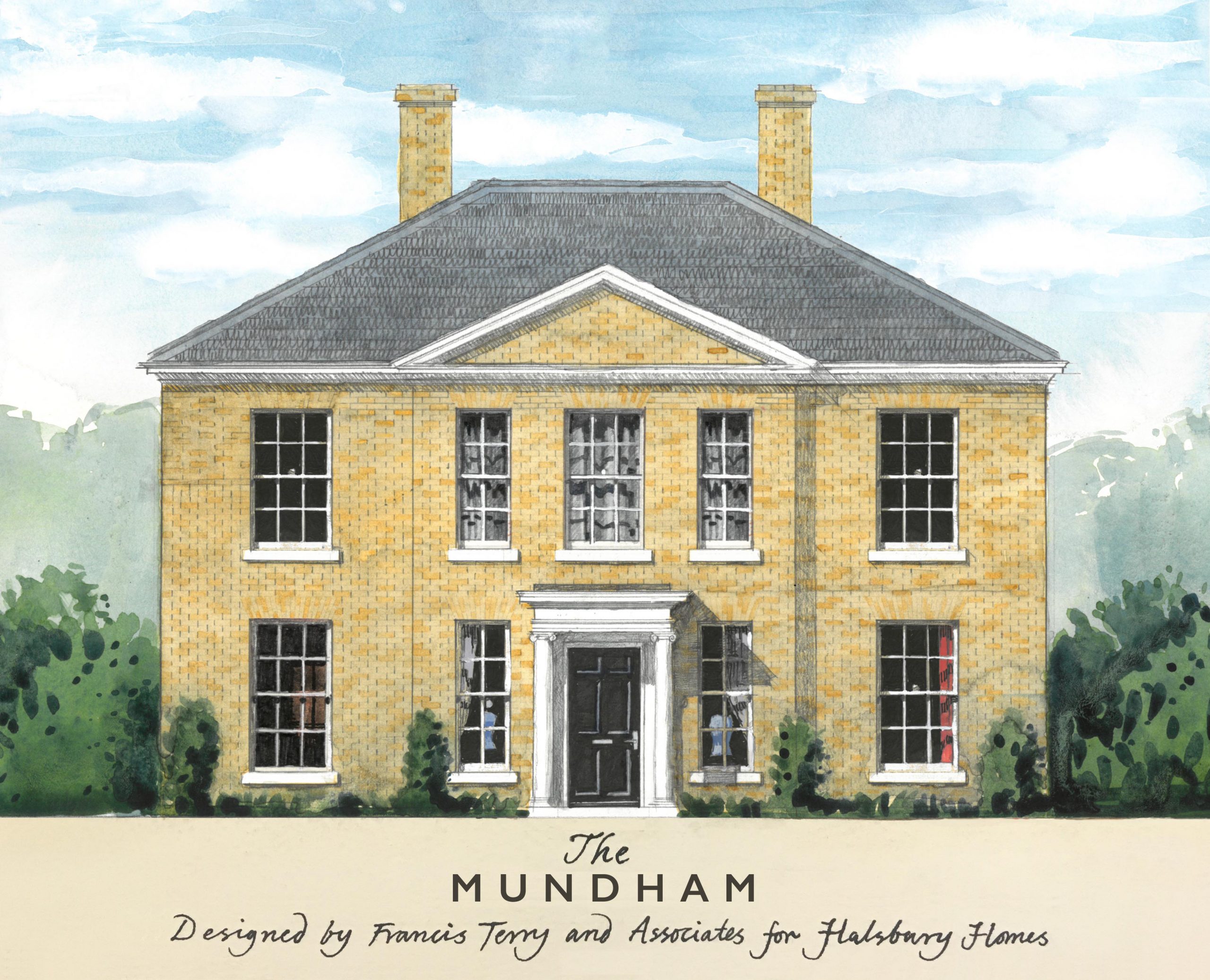

In a scheme at Loddon in Norfolk, for a new developer called Halsbury Homes, Mr Terry has taken a different approach. ‘My aim was to make the houses as similar as possible. They look as if they’re by the same hand, with sash windows, brick and occasionally porches or pediments, depending on the size of the home.’

The budget, although tight, is higher than it would be for a volume house builder—but Halsbury Homes is building a brand that will ultimately enable it to charge more for its product. In the meantime, it is creating settlements of which anyone could be proud.

VAT

Not all housing has to be newly built. After the pandemic, we desperately need to regenerate our town centres and there are hundreds of thousands of potential residential units above shops that might usefully be used for housing, not to mention the potential for development over modern retail parks.

As an added incentive, there is the issue of climate change, which should encourage us to recycle the architecture we have. Yet the application of VAT on the restoration of buildings and its absence on new-build constitutes a massive financial incentive to demolish buildings wholesale.