The man who made Mayfair

Thomas Cundy II changed the face of Mayfair with the refronting programme he launched as chief surveyor of the Grosvenor estate, but much of his work was lost in subsequent renovation, as Carla Passino discovers.

On November 1850, a mob gathered in the streets of Pimlico, so large and so irate that it threatened to pull down a gate. The unlikely cause of the fracas was a church that had opened only five months earlier: St Barnabas, where curate W. J. E. Bennett, a Ritualist, had revived liturgical practices reminiscent of Catholicism. At a time when, in the wake of the Catholic bishops’ return to Britain earlier in the year, anti-Popish feelings ran high, Ritualism was viewed with suspicion — hence the crowd’s attempt to storm the service and stop the ‘Popery’. The Pimlico church, however, also drew (rather more measured) disdain from an otherwise sympathetic quarter: the influential Ecclesiological Society, which promoted Gothic Revival architecture in churches. The group dismissed St Barnabas as too bland and too ambitious at the same time. ‘The western elevation is not successful, owing to its attempting more than the dimensions of the church justified, and claiming to be, as it were, a miniature cathedral façade,’ thundered the Society’s journal, The Ecclesiologist, in 1850.

But if St Barnabas was redeemed by fittings and internal decorations that made it ‘the most complete, and, with completeness, most sumptuous church which has been dedicated to the use of the Anglican communion since the revival’, there was no saving grace for its clergy house and parochial school: ‘We shall not dwell upon the architecture of these buildings, because we cannot bring ourselves to consider them altogether worthy of the church to which they are attached.’

There is no way to tell what the architect of St Barnabas, Thomas Cundy II, made of the controversies that swirled around his work, but they certainly didn’t affect his career. By then, he had already been in the trade for at least 43 years — having shown some drawings at the Royal Academy in 1807, at the tender age of 17 — and had designed numerous churches, mostly in Gothic Revival style, including, in London, St Paul’s in Knights-bridge, of which the Ritualist Bennett had also been curate; the sadly demolished Holy Trinity in Paddington; St Michael’s in Pimlico’s Chester Square, where Cundy lived; and, with his son, Thomas, the glorious St Mark’s in Hamilton Terrace, which was gutted by a fire just over a year ago (donations to help with the restoration can be made at www.stmarks.london). Nor did the wrangle hamper Cundy’s continued success: after St Barnabas, he would go on to design St Gabriel’s and nearby St Saviour’s, the spires of which pierce the sky above Pimlico.

But there was more to the architect than Gothic Revival churches. Although he built very few houses from the foundations up, he’s the man that, with Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Marquess of Westminster, most shaped Mayfair and Belgravia at the time — perhaps even more than the celebrated Thomas Cubitt (‘Pillar of society’, July 5, 2023). The elder son of architect Thomas Cundy I, he followed his father into the profession, working with him even after Thomas the elder was appointed chief surveyor to Robert, 2nd Earl of Grosvenor (later 1st Marquess of Westminster) in 1821. Together, the Cundys merged two houses in Grosvenor Square to form a house fit for a Viscount (Belgrave, later the 2nd Marquess of Westminster): it was a giant of a building, iced in 75ft of stuccoed front and split by four engaged columns, which soared for two floors to die in a triumph of Corinthian foliage under a frieze.

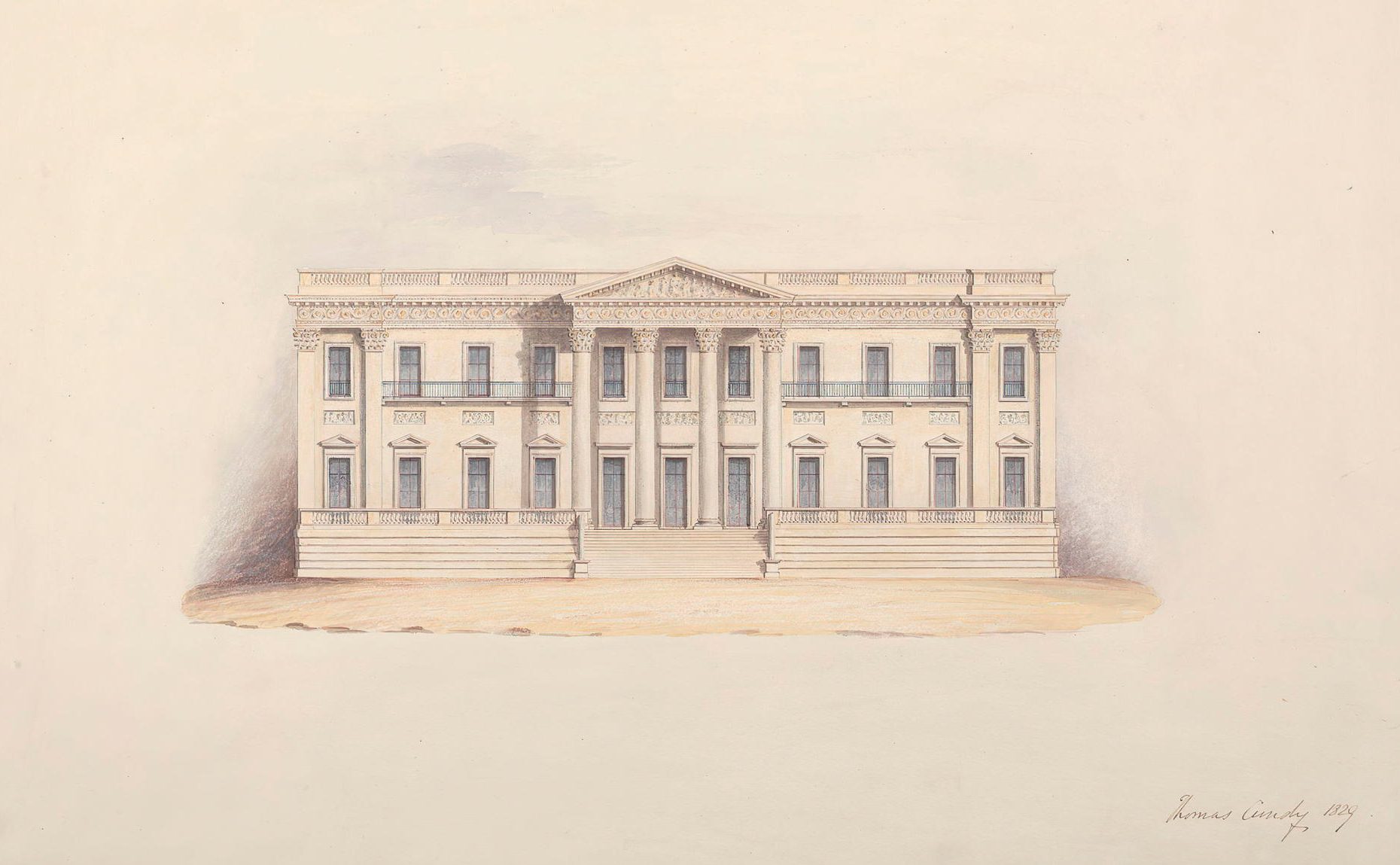

Father and son also helped forge Belgravia, where they ‘regularly vetted the elevations and dimensions of all building and rebuilding projects,’ as architectural historian Andrew Saint wrote in COUNTRY LIFE on November 17, 1977. They were drawing plans to remodel Grosvenor House for the 2nd Earl when Cundy senior died in 1825. His son succeeded him both in the practice and in the estate-surveyor role. Although relatively young, Cundy II didn’t lack ambition, at least when it came to scale — one of his designs for Grosvenor House, dating from 1826, shows a neo-Classical behemoth more than 230ft long. Eventually, however, the only substantial alteration carried out in 1826–27 — at the considerable cost of almost £23,000 (more than £2 million in today’s money) — was the extension and renovation of the Roman-style picture-gallery wing, a massive, columned affair in Bath stone.

Although Cundy would continue presenting remodelling plans over the years and add a Doric screen to the Upper Grosvenor Street front almost two decades later, his Grosvenor House design never came to life in its entirety, possibly because Lady Grosvenor wasn’t keen to tear down her original home or perhaps because Lord Grosvenor, however wealthy, had grown alarmed at the amount of money he was haemorrhaging on the renovation project: as early as 1827, he instructed his agent to ‘tell Cundy I am particularly anxious nothing should be done or undone and no unnecessary expense, no undue haste particularly’. It was probably for the better that the scheme was never completed, considering that Survey of London, not mincing words, called it ‘essentially pedestrian’ and a ‘heavy Roman effort’.

Although he may not have made as big a mark on Grosvenor House as he might have liked, Cundy did mould the surrounding estate. Like his father before him, he, as chief surveyor, had a say in the look of new houses and the remodelling of existing ones, as well as designing the odd building (the south side of Belgravia’s Chester Square, built by his brother Joseph in 1828, and the 1830s façade of 53, Davies Street, then the Grosvenor estate office, were likely both his). In 1844, reports Survey of London, he had persuaded the 1st Marquess of West-minster to improve Grosvenor Square by ‘adding stuccowork, porticos, window dressings, cornices and balustrades … to “such of the houses as may be thought to require it”’. However, it was after the 2nd Marquess took over the estate in 1845 that Cundy really embarked on the great Mayfair facelift. Although slow at the outset, the plan took off when, with a few exceptions, refronting became a condition for new leases.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In a bid to modernise Georgian Mayfair, Cundy designed at least 40 façades, giving them porticos and ‘Italianate trimmings in stucco or stone’, according to Mr Saint. The house at 52, Grosvenor Street — a mid-1850s reworking of an early-18th-century building — captures the essence of his vision in a jubilation of stucco, Doric portico, balconettes and window dressings. When Cundy’s son Cundy III came into his own from the mid to late 1850s, the family’s style evolved to acquire the French Renaissance touch he so favoured — he used it liberally in designing several Oxford Street shop fronts, sadly now lost, and at Grosvenor Gardens, where ‘lofty and handsomely constructed houses’ earned the praise of near contemporary Edward Walford in Old and New London.

This zeal for renovation could occasionally be devastating: as Survey of London puts it, ‘Cundy II and the 2nd Marquess were not sensitive souls when it came to the architecture of the past’. One of the buildings that fell victim to their ‘improvements’ was early-18th-century Derby House in Grosvenor Square, the interiors of which had been entirely redesigned by Robert Adam in 1773–75: it was first refronted, then, in 1862, demolished and rebuilt.

Architectural karma, however, must have been waiting round the corner, because not much of the Cundys’ work survived the tenure of Hugh Grosvenor, 3rd Marquess of Westminster (later 1st Duke), who succeeded his father in 1869. By then, Cundy II was dead and although Cundy III inherited the position as the Grosvenor Estate’s chief surveyor, that’s all he did — the 3rd Marquess put an end to the refronting programme and when he launched his own rebuilding project in the 1880s, he brought in a variety of architects that made short work of the Cundys’ legacy. Only their churches survived relatively unscathed — proof that it is easier for a building to withstand a mob than to survive a renovation frenzy.

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson Published

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher Published

-

A gorgeous home that offers a slice of country life in the heart of Hampstead

A gorgeous home that offers a slice of country life in the heart of HampsteadThis idyllic Hampstead mansion has seen its price rise nine times faster than inflation — and it's not hard to see why.

By Carla Passino Published

-

What the Monopoly board would look like at 2024 property prices

What the Monopoly board would look like at 2024 property pricesIn the 88 years since the first British edition of Monopoly, a lot has changed. But how much should the various properties be worth today? And where should they be on the board?

By Toby Keel Published

-

A country house in central London? The £10m Primrose Hill home on the square where Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes once lived

A country house in central London? The £10m Primrose Hill home on the square where Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes once livedA house has come up for sale on one of the most beautiful — and most photographed — streets in London. Rachael Turner explains more.

By Rachael Turner Published

-

A 'country house in London' for sale in Hampstead, complete with quirky murals

A 'country house in London' for sale in Hampstead, complete with quirky muralsLocated in one of London’s most sought-after neighbourhoods, this Grade II-listed property could set you back £11,000,000. And that’s before you revamp it.

By Annabel Dixon Published

-

A riverside mansion with keys to south west London's secret garden

A riverside mansion with keys to south west London's secret gardenThis dreamy property has a stunning pool, a gym, wine cellar and cinema, plus access to the exclusive Pleasure Gardens, a 12-acre green space with tennis courts and lake.

By Rachael Turner Published

-

How the Bloomsbury Group shaped life in London WC1

How the Bloomsbury Group shaped life in London WC1There’s more to the Bloomsbury Group than squares, circles and triangles, says Rosemary Hill, who explores what drew its members to London’s WC1 in the first place and the lasting effect they had on it.

By Country Life Published

-

Hugh Grant's former South Kensington penthouse on the market with £700k price cut

Hugh Grant's former South Kensington penthouse on the market with £700k price cutI'm just a girl, standing in front of a 3,000 sq ft London penthouse, asking it to please let me in.

By Carla Passino Published

-

What it's like living in the heart of central London: 'I'd see St Paul’s and know that I was almost at my front door. It was amazing and bizarre’

What it's like living in the heart of central London: 'I'd see St Paul’s and know that I was almost at my front door. It was amazing and bizarre’The majority of us only pass through the heart of London, more commonly known as Zone 1, for work or play, but, for some people, it’s home. Emma Love meets the residents with Trafalgar Square on the doorstep.

By Country Life Published