One of the most incredible privately-owned homes in Britain has come to the market

The magnificent Athelhampton House in Dorset is a manor with spectacular Tudor interiors, 19th-century formal gardens and a fascinating history.

One of Dorset’s most exquisite Tudor manors, Grade I-listed Athelhampton House near Puddletown, has come to the market . This extraordinary property, which lies six miles from the county town of Dorchester and 11 miles from the coast at Ringstead Bay, is for sale at a guide price of £7.5 million through the country departments of Knight Frank and Savills.

Seeing Athelhampton House in all its early-spring glory, it’s hard to imagine that the historic stone house has risen more than once from the ashes of disaster, thanks to the efforts of an inspired and dedicated few. They include the Martyn family, who built the house in the late 15th and mid 16th centuries; the antiquarian Alfred Cart de Lafontaine, who restored it and created its magnificent formal gardens in the late 1800s; and its present owners, the Cooke family, who, during a 62-year tenure, have built on and enhanced the legacy left by the best of Athelhampton’s many previous owners.

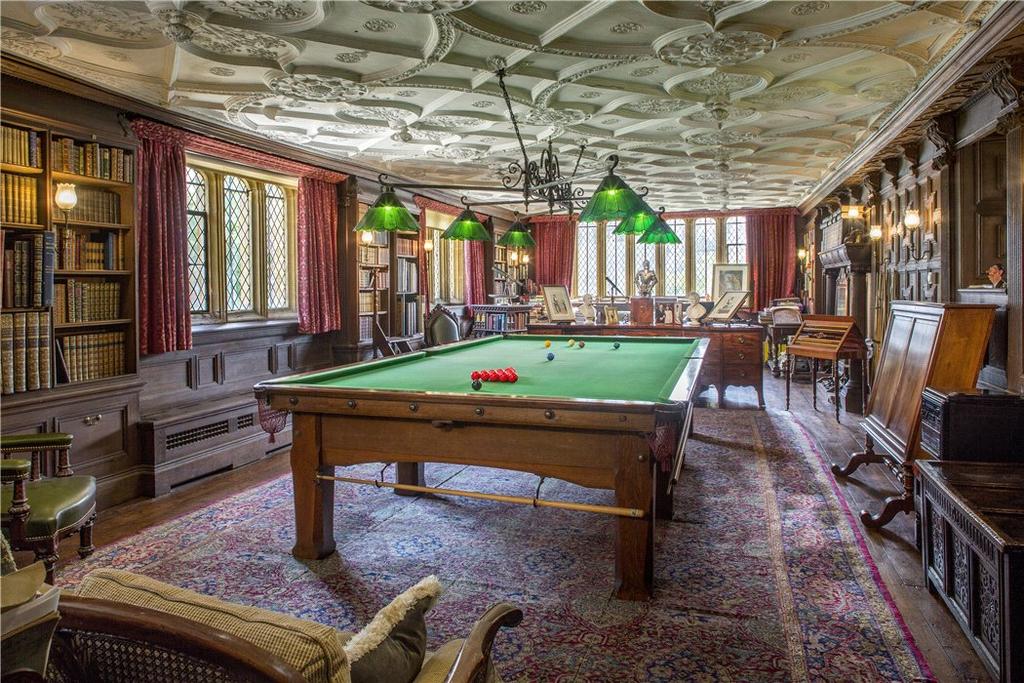

The glories of Athelhampton House and its 29 acres of exquisite formal and informal gardens bounded by the River Piddle, are too numerous to list here. Worthy of special mention, however, are the Great Hall, one of the finest examples of 15th-century domestic architecture in England; the oriel window, which depicts the marriage alliances of the Martyns; and the Great Chamber, with its elaborate plaster ceiling based on a pattern from the Reindeer Inn at Banbury, which was added by Cart de Lafontaine in about 1905.

Also of note are the King’s Room, the original 15th-century solar, so called because the manorial courts held in the name of the king took place here; the dining room or Green Parlour, decorated by Cart de Lafontaine and restored in the 20th century; the State Bedroom, with its 15th-century fireplace; and the main staircase, rebuilt by the Cooke family using Jacobean oak from the demolished priory at Bradford-on-Avon.

The private family rooms are housed in the east wing, the second floor of which has been converted to a conference facility with a large auditorium-cum-cinema.

The pretty thatched coach house, refurbished throughout in 1997, forms the heart of the commercial operation at Athelhampton, with further accommodation available in the three-bedroom River Cottage, another charming thatched house, accessed over a bridge across the River Piddle.

According to a series of scholarly articles by Clive Aslet, then Architectural Editor of Country Life (May 10, 17 and 24, 1984), Athelhampton came to the Martyns when successive generations, Robert and his son, Sir Richard Martyn, married Athelhampton heiresses. Sir Richard’s grandson, William, was a canny operator who married twice, each time into a rich West Country family, and prospered in business under three monarchs — Edward IV, Richard III and Henry VII — before being elected Mayor of London in 1492 and knighted two years later.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘Shrewd as ever, Martyn waited a decade before deciding that England after Bosworth was safe to build in. The licence to crenellate Adlampston, as his manor house was called, was given on November 5, 1495… Built of whitish limestone with Ham Hill stone dressings [it] preserved a perfect medieval arrangement of porch, hall, oriel and service wing, which can still be seen,’ noted Mr Aslet.

The oldest part of Athelhampton House and still an impressive focal point is the magnificent Great Hall, built in about 1485, with its timbered roof, linenfold panelling, minstrels’ gallery and heraldic glass windows.

The west wing and a gatehouse were added by Sir William’s descendants in about 1550, although the gatehouse was demolished in the early 1860s in the course of a restoration by a subsequent owner, the self-important George Wood – an intervention that caused outrage in conservation circles at the time.

A series of earlier Country Life articles (June 2, 9 and 23, 1906) recalls the ending of the Martyn male line with the death of Nicholas Martyn in 1595/96; the inscription tombstone in the Athelhampton chapel of St Mary Magdalene at Puddletown salutes him with grim humour with the words: ‘Nicholas the First and Martyn the Last,/Good night, Nicholas!’

Nicholas’s three sons had died young, so the Athelhampton estate passed to his four married daughters, none of whom wanted to live there. Eventually, it was sold to Sir Robert Long of Draycot Cerne and passed through the Long family to the Duke of Wellington’s spendthrift nephew, William Pole-Tylney-Long-Wellesley. According to Country Life, ‘this worthless person succeeded in 1845 as 4th Earl of Mornington and died in 1857, having wasted his estates’. By 1848, he had already sold Athelhampton to his former tenant, George Wood.

The Longs never lived at Athelhampton and the 18th century had seen it let to tenant farmers, so ‘from being a house of knights and squires, the old hall had sunk to the slovenly estate of a farmhouse… like an old charger in the shafts of a haywain’.

Despite Wood’s restoration, Athelhampton was again in a poor state by 1891, when it was bought by Cart de Lafontaine, who set out to restore the house to its former glory, using much of the material recovered from the former gatehouse, chapel and other buildings demolished by Wood.

The great Tudor gatehouse still existed when Athelhampton was first visited by Thomas Hardy, who lived at nearby Bock-hampton and immortalised the romantic old manor house, thinly disguised as Athelhall, in the short story The Waiting Supper and the poems The Dame of Athelhall and The Children and Sir Nameless.

Cart de Lafontaine commissioned Inigo Thomas to design one of England’s finest gardens as a series of ‘outdoor rooms’ inspired by the Renaissance. The sinking of the entire ground level about the hall, due to poor drainage, was Cart de Lafontaine’s first major project. There followed lawns, terraces and walled gardens, with 40,000 tonnes of Ham Hill stone going to create the picturesque walls and terraces now standing ‘where were cowsheds, and ruinous stables and linhays’.

Having lost his heir and his fortune during the First World War, Cart de Lafontaine sold his beloved Althelhampton in 1916. It was bought by George Cochrane, who built the north wing in 1920–21, before selling in 1930 to the Hon Mrs Esmond Harmsworth, who entertained lavishly there.

The house was sold again in 1933 and reappeared in the advertisement pages of Country Life in 1946, when it was described as a ‘XVth century Mansion of rare architectural charm, and of great historical association, in a remarkable state of preservation, carefully restored and brought thoroughly up-to-date with all modern comforts’.

In 1957, Athelhampton House was bought by the eminent surgeon Robert Victor Cooke, who restored the manor as a home for his retirement and to house his extensive collection of 16th- and 17th-century furniture, paintings, tapestries and carvings. Following his wife’s death in 1964, he gave the house to his son Robert Cooke MP (later Sir Robert) on his marriage to his wife, Jenifer King, in 1966.

After the death of Sir Robert in 1987 and Jenifer in 1995, Patrick Cooke inherited the house. He continued its restoration and extended the gardens, all listed Grade I, with his wife, Andrea.

Having worked tirelessly to build a thriving family enterprise at Athelhampton, which is open to the public all year round, Mr Cooke is looking forward to embarking on the next phase of his life, in which the knowledge and experience gained over 30 years or more at the helm of this remarkable Dorset manor will, no doubt, serve him well.

Athelhampton House is for sale at a guide price of £7.5 million through Knight Frank and Savills. See more pictures and details.

For sale: The last of Wentworth's original houses, and the latest of its new breed

Penny Churchill uncovers two gorgeous family homes for sale in this exclusive area.

Credit: Knight Frank

Fortgranite: A magnificent Irish estate for sale for the first time in its history

After a rich history of family ownership, this country estate is ready to start a new chapter. Penny Churchill reports.

Credit: Galbraith

A completely self-sustaining house in one of the most remote, idyllic locations imaginable

No. 2 Doune sits on the Knoydart peninsula, known for it’s close knit community, turbulent history and spectacular countryside.

-

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'Minette Batters explains why she's taken a job at Defra, and bemoans the closure of the Sustainable Farming Incentive.

By Minette Batters Published

-

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the world

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the worldWhere else on Earth can you find more than 752,000 acres of splendid isolation? Words and pictures by Luke Abrahams.

By Luke Abrahams Published

-

A Grade II*-listed country manor with one of the most beautiful drawing rooms in England

A Grade II*-listed country manor with one of the most beautiful drawing rooms in EnglandIf Old Manor Farm in Somerset is good enough for Pevsner, it's good enough for you.

By Penny Churchill Published

-

An eight-bedroom home in Surrey where an army of robots will look after your lawns

An eight-bedroom home in Surrey where an army of robots will look after your lawnsDo not fear the bladed guardians of Monksfield House. They are here to help.

By James Fisher Published

-

A French castle for sale on the banks of the Dordogne? With a swimming pool? Where do we sign?

A French castle for sale on the banks of the Dordogne? With a swimming pool? Where do we sign?This chateau in Lalinde is nothing short of a historical delight in the south of France. And it comes fully furnished.

By James Fisher Last updated

-

Sip your morning tea where Churchill once paced, as his former Pimlico home comes up for sale

Sip your morning tea where Churchill once paced, as his former Pimlico home comes up for saleThe five-bedroom flat in Eccleston Square offers ‘historical gravitas and modern comfort’ in a leafy pocket of London.

By Annabel Dixon Published

-

Live a life of Tudor fancy in this five-bedroom London home with links to Cardinal Wolsey and Henry VIII

Live a life of Tudor fancy in this five-bedroom London home with links to Cardinal Wolsey and Henry VIIIFans of Wolf Hall rejoice, as a rare chance to own a Tudor home inside the M25 comes to market.

By James Fisher Published

-

Murder, intrigue and 'the magic of a bygone era' at this eight-bedroom home set in 25 acres of Devon countryside

Murder, intrigue and 'the magic of a bygone era' at this eight-bedroom home set in 25 acres of Devon countrysideUpcott Barton is a family home steeped in history and comes with more than 5,000sq ft of living space.

By Penny Churchill Published

-

The 'best places to live' ranking that lists all 1,447 towns, cities and large villages in England and Wales — who is this year's winner?

The 'best places to live' ranking that lists all 1,447 towns, cities and large villages in England and Wales — who is this year's winner?Redbourn has been named the best place to live in the country.

By Annabel Dixon Published

-

A six-bedroom house in Wales with estuary views and some gloriously fun interiors

A six-bedroom house in Wales with estuary views and some gloriously fun interiorsBrynymor House is somehow more beautiful on the inside than the outside.

By James Fisher Published