Restoring a Georgian kitchen

William Palin finds that restoring his Georgian kitchen is not as easy as one might expect, and in fact the one he ends up designing leaves much to be desired

Unlike today, kitchen design was not a preoccupation in the 18th century. In those blissful days, the formula was very simple — a basement room with a capacious fireplace and range, a larder, a few buckets and copper for washing, a table, a dresser, a bench and some servants. No interminable discussions about work surfaces with a man from John Lewis, and no marriage-threatening rows over the choice of dishwasher.

* Find more on restoring Georgian property on our dedicated webpage

In the modern age, however, the humble kitchen has evolved into a sophisticated entity where cooking, eating, and conversation must all take place. And, in a historic building, the fitting up of a room that combines these functions can be a tricky thing to achieve. In Spitalfields, east London, where many of the houses date from the early 18th century, the basement kitchen is still popular—being out of the way of the panelled rooms above, naturally cool, and able to take a stone or tiled floor.

However, set against these benefits can be the lack of natural light and the awkwardness of getting food upstairs to a dining room. I was astonished to find in the basement of my 1717 house the remnants of the original Georgian service area—the copper survived as did part of the built-in dresser (which I later restored). I considered re-using the room, but it was damp and gloomy (and at that time had only an earthen floor). The fact that the panelling had sadly gone from the floor above gave me the chance to create a new room there — enjoying the benefit of a large south-facing window — without damaging the original fabric.

My new kitchen was very much a home-grown affair. I sat down with a carpenter and, together, we settled on a design. He had recently acquired some good-quality pitch pine from a demolished distillery, so we used this for the worktops (treated with tung oil, it makes a durable and forgiving surface — any scratches can be sanded down easily) and the units were made from MDF and painted (the simple panelled doors copied from the 18th-century doors and panels elsewhere in the house). The resulting kitchen looks nice but, thanks to my involvement, it contains a number of comedy defects. Cupboards are too shallow for plates, certain doors and drawers cannot be opened together, and the knobs keep falling off. My neighbours' efforts have, on the whole, been more successful.

The prize for sheer inventiveness must go to Tim Whittaker, whose 'secret' kitchen in the compact basement of his house in nearby Whitechapel defies all convention. At first glance, it appears to consist only of a table and a fridge, but a little investigation reveals a dishwasher, a sink, an oven, even a washing machine all hidden away in old cupboards and behind panels. Thus, refined diners can enjoy the authentic Georgian atmosphere without the ugly flash of chrome or the intrusion of an LED light to break the elegant illusion. So the lesson here is to be creative. Very old houses demand flexible solutions and off-the-shelf fitted kitchens rarely make the best of historic features. Just make sure there is enough room for the plates.

* Find more on restoring Georgian property on our dedicated webpage

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?The team behind London's first mixed-use ‘wellness village’ says it has the magic formula for tempting workers back into offices.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

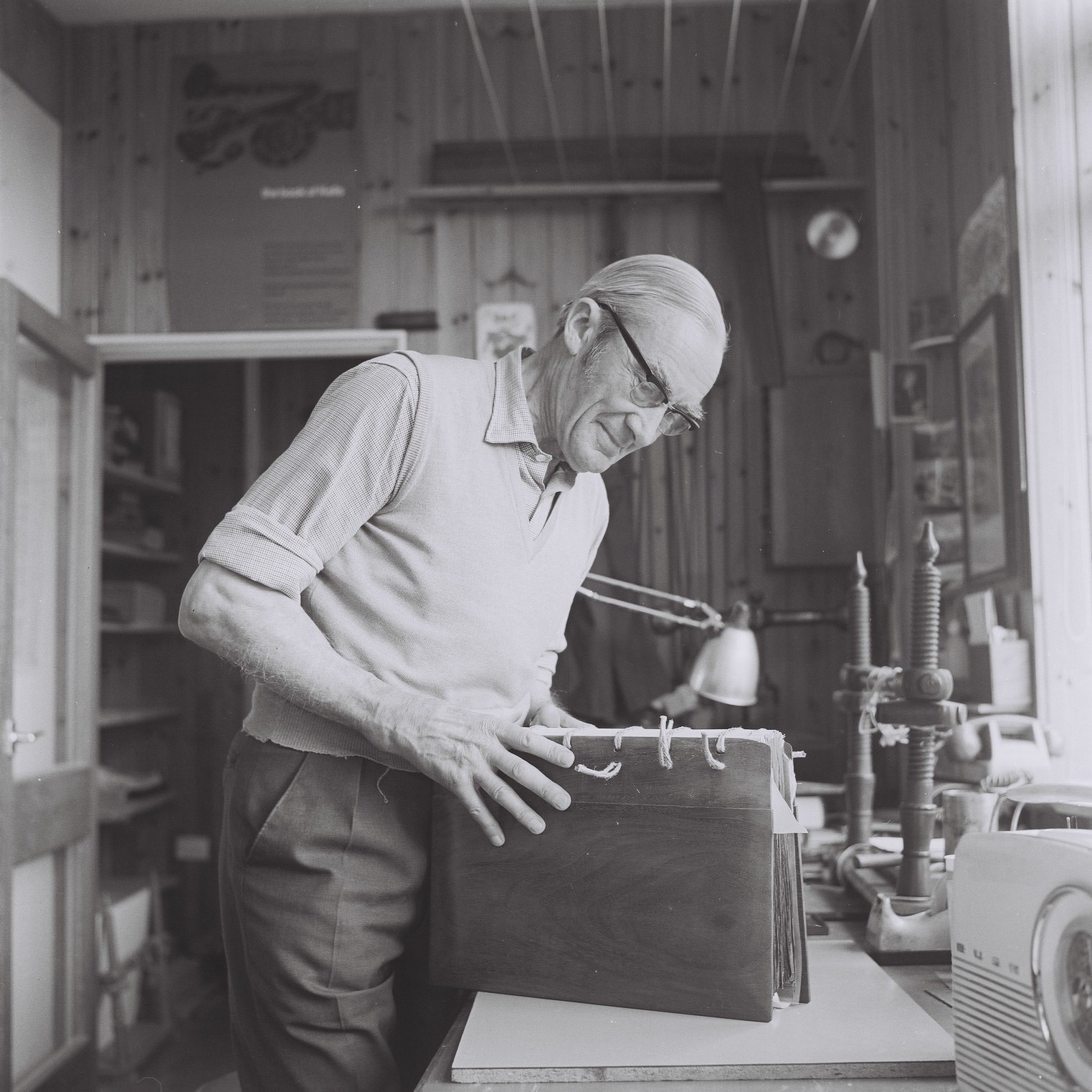

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani