Finding an architect in Scotland

Mary Miers talks to an architect in Scotland whose buildings represent a traditional yet contemporary vernacular

Lachie Stewart'S buildings represent many of the core values of Country Life. Brought up in the West Highlands and trained at Edinburgh Art School, he has created from a 'simple palette of key building types the cottage, farmhouse, steading, small laird's house and castle' a new vernacular that is traditional yet refreshingly contemporary. 'My grandfather was a stonemason, and my mother taught me to value things of quality. It was a great lesson the idea that if you're going to make something, you should wait for the right opportunity, and until you can afford to do it well.' Juxtaposed with the Highland vernacular was the discipline of Scandinavian Modernism, which pervaded the Edin-burgh architectural scene when Mr Stewart was a student. The simple, stripped down aesthetic that characterises his work today has roots in both traditions. He regards the late Colin McWilliam, the architectural historian and pioneering conservationist who ran Edinburgh Art College's post-graduate course, as the one person who really influenced him. 'Colin opened my eyes to the buildings and traditions of the Scottish landscape and his book, Scottish Townscape, is a seminal work.' Mr Stewart's first solo commission was a programme of repair works at Eilean Donan Castle, which he undertook after working for a spell at Ian Hurd and Partners, a firm well known for its understanding and sensitivity towards the Scottish vernacular. He now runs an architectural practice, employing five, that is one arm of the successful design business, Anta, which he and his wife, Annie, a textile designer, founded after they married in 1985. Based near Tain in the Highlands, with shops in Edinburgh and London, the company's ethos is about delivering a unified aesthetic, so that 'architecture, interior design, furnishings and garden all speak to each other'. If you build with materials of good quality, Mr Stewart believes, then you can keep the design and proportions simple. 'The biggest compliment anybody can pay me is to think that I've restored an old building, when, in fact, it's new.' Colour, used within a restrained palette of building forms, is also extremely important to his work, and he is not afraid to use it boldly. He enjoys, for example, contriving to have a shaft of intense colour, perhaps on the wall of a staircase or small adjoining room, glimpsed through a doorway. 'There's a whole book to be done on the use of colour in Scottish buildings.' Mr Stewart's empathy with traditional materials and craftsmanship and the aesthetic qualities of old buildings owes a strong debt to houses such as Newhailes near Edinburgh, where he lived as a student, and the Arts-and-Crafts masterpiece, Daneway, in the Cotswolds, where he also lived. Then there was Plockton lighthouse, the Stewarts' first marital home, with no electricity and accessible only by boat, and the 18th-century house in Spitalfields, which they completely restored. 'That was a huge learning curve; a joiner friend came down from Plockton and we stripped everything down, and then put it all back together again, properly.' But perhaps the most important influence on the architect's career has been Ballone Castle, a late 16th century tower house overlooking a dramatic rocky beach near Portmahomack, which the Stewarts bought as a roofless shell in 1990 and restored as their home. The practice is currently building or remodelling a number of shooting lodges (such as Kylestrome in Sutherland), the designs for which reflect the influence of the vertical, sculptural forms and spatial qualities of Scottish tower houses, and it has built several visitor centres one for Eilean Donan, and one (newly opened) for the Castle of Mey, where Mr Stewart is involved as architect. His current involvement with the proposed development of a new town near Inverness, takes Anta in an exciting new direction.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

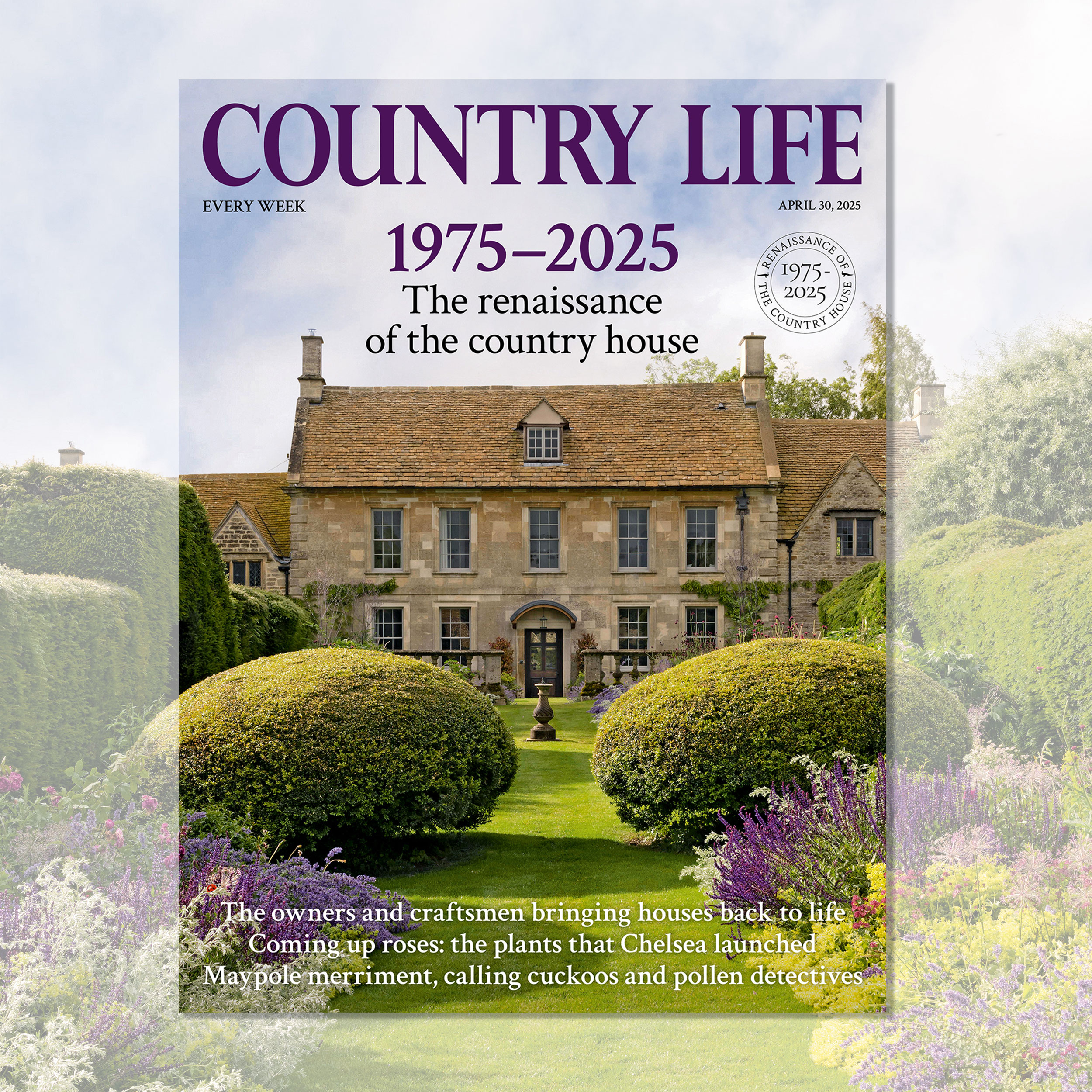

Country Life 30 April 2025

Country Life 30 April 2025Country Life 30 April 2025 is a glorious celebration of the country house in Britain, and the tale of its renaissance in the last fifty years.

By Country Life Published

-

About time: The fastest and slowest moving housing markets revealed

About time: The fastest and slowest moving housing markets revealedNew research by Zoopla has shown where it's easy to sell and where it will take quite a while to find a buyer.

By Annabel Dixon Last updated