Curious Questions: Are heat pumps actually worth it?

Mention heat pumps and you'll get a decidedly mixed reaction — but do the sums actually add up? Lucy Denton investigates.

‘There isn’t a building in the country that can’t be heated effectively with heat pumps,’ says Will McCarthy, senior consultant at ISO Energy in Horley, Surrey, ‘and it’s a myth that it can’t be done. It can be made to work, as long as it’s designed and installed correctly.’ The pressure is on to reduce carbon emissions and heat pumps have emerged as an energy-source antidote to the old fossil-fuel guzzling gas and oil boilers, endorsed by the Government offering grants of £5,000 or more to potential takers, as long as a new system meets certain standards. Yet, the response has been lacklustre, a curiously British phenomenon that means a significant lag behind other countries. ‘It will take time to catch up with the rest of Europe,’ adds Mr McCarthy.

Heat pumps have become a divisive subject, rousing bad press, notably for the hefty fees for purchase and installation, which often run into tens of thousands of pounds, and for the long wait for cost benefits. ‘What any good installer should do is produce calculations showing expenditure and payback time, but be aware that this could potentially extend beyond your lifetime,’ points out Ed Stancliffe, senior design engineer at ENG Design, based in London. The physical impact on the historic built environment can be invasive and the planning process protracted, depending on availability of conservation officers. Ground-source pumps require expensive bore holes or trenches to be dug by specialists, whereas air-source units can be noisy and unsightly. Both work best when combined with effective insulation, ‘which I would promote ahead of everything, where possible,’ says Mark Hoare, director at Hoare, Ridge & Morris architects in Suffolk, who has installed a ground-source heat pump at his own 16th-century timber-frame cottage and has ‘no regrets’.

There are more encouraging stories: at Grade I-listed Dorfold Hall in Cheshire, a superlative Jacobean brick-built house intended to accommodate a visit from James I, the tradition of shrewd development has been fulfilled in the 21st century. Here, one of the first heat-pump systems installed at a country domain, combining both ground- and water-source energy from a nearby field and lake, has been nothing short of transformative in the effort to be sustainable, particularly as the electricity that powers it comes from renewable sources. ‘It required a significant investment, but it changed our lives,’ stresses Candice Roundell, custodian of Dorfold, ‘and it has outperformed our initial expectations. It’s the best thing we ever did. And it works especially well in historic houses where the constant temperature it generates benefits the collections and fabric of the building.’

There is an auspicious synchronicity between rural stately piles, with all their outbuildings and land, and the practical requirements of ground- and water-source energy. What is still the Roundells’s family home has a huge ‘boiler’ room on site, allowing space for water tanks and heat pumps in the clocktower — to the naked eye, there is no obvious sign of this state-of-the-art system.

However, the dynamics of each building will be unique and thought must be given to a site’s age, location and function. The surprisingly wide variation in results when traditional boiler systems were replaced with heat pumps has been uncovered in a case study of 10 small-scale historic properties recently produced by Historic England in collaboration with Max Fordham LLP, net-zero technology specialists, which analysed impact on churches, private dwellings and retail units. ‘There are effective solutions in buildings of all sizes and ages,’ concludes Morwenna Slade, head of historic-building climate-change adaptation at Historic England, ‘but it is not a case of one size fits all. Heat pumps are effective when situated properly and the resident knows how to use the system.’

It depends on how the building is employed: a modest congregation occupying a mid-19th-century church only intermittently, which got cold throughout the rest of the week, found that the underfloor heating powered by an air-source heat pump took too long to warm up days later. Yet a similar set-up proved very efficient in providing a constant ambient temperature and eliminating condensation at a Georgian equivalent in Cumbria that was more frequently operational.

Investing in companies and planners with good knowledge of these systems in order to produce an optimal design that is fit for purpose is essential, otherwise ‘it can be deeply frustrating,’ points out Rob Jones-Davies, a director of the RJD Consultancy, which specialises in rural development, ‘especially when a very expensive heat pump is installed by a specialist, who then defers to a local plumber for everything beyond the plant room, so you’re dealing with two different suppliers. And internal infrastructure often has to be replaced.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Heat pumps produce a lower temperature and existing pipework will almost certainly need to be updated with an increased diameter, so that heat isn’t lost. If retrofitting a new system, the existing radiators won’t be as hot and may also need changing. Mr Stancliffe advises starting with a heat-loss calculation with a sensible worst-case external temperature, cautioning that ‘unless you know how much heat that building requires, it is only half the game. If you don’t know the heat loss, then you’re guessing at the amount of heat you need. In the case of ground-source heat pumps and their collectors, it’s a good idea to have one contractor responsible for it all, to ensure compatibility’.

Interventions in the historic fabric of listed buildings will also require formal consents from the local planning authority, who will ‘need to decide whether the harm caused to the building by the upgrades is outweighed by the benefits offered,’ says Alice Jones of Savills’s heritage-planning team, although ‘we are seeing a shift in attitudes from officers and the public benefit of improving the energy efficiency of a building is being given more weight in this balance’. Fitting heat pumps is a complex operation, with heating requirements in different rooms, amount of space and land and geology all being factors, even the potential for snow build-up and how many baths will be run at the same time — although maintenance is usually no more than for a ‘traditional’ oil or gas system. There are ways around what might seem like problematic circumstances, including combining boreholes and dry-air coolers for multi-storey blocks; ISO Energy has even designed systems to be buried under car parks, extensions, in paddocks and registered parkland. Some do, indeed, like it hot-ish.

Lucy Denton is a writer and architectural historian. She has worked for Adam Architecture, Sotheby’s and ArtUK, and has written for Hudson’s Historic Houses and The Times. She writes regularly for Country Life.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher Published

-

John Sutcliffe — The man, the myth and the paint-naming legend behind Dead Salmon and Elephant's Breath

John Sutcliffe — The man, the myth and the paint-naming legend behind Dead Salmon and Elephant's BreathBy Carla Passino Published

-

What the Monopoly board would look like at 2024 property prices

What the Monopoly board would look like at 2024 property pricesIn the 88 years since the first British edition of Monopoly, a lot has changed. But how much should the various properties be worth today? And where should they be on the board?

By Toby Keel Published

-

Curious Questions: Can you really live off the grid in 2022?

Curious Questions: Can you really live off the grid in 2022?The pandemic forced millions of us to re-evaluate where and how we live — and what's important to us. The answer for many was to live off the grid. But can it really be compatible with modern life? Adam Hay-Nicholls tried it out — and spoke to some of those who have made it work.

By Adam Hay-Nicholls Published

-

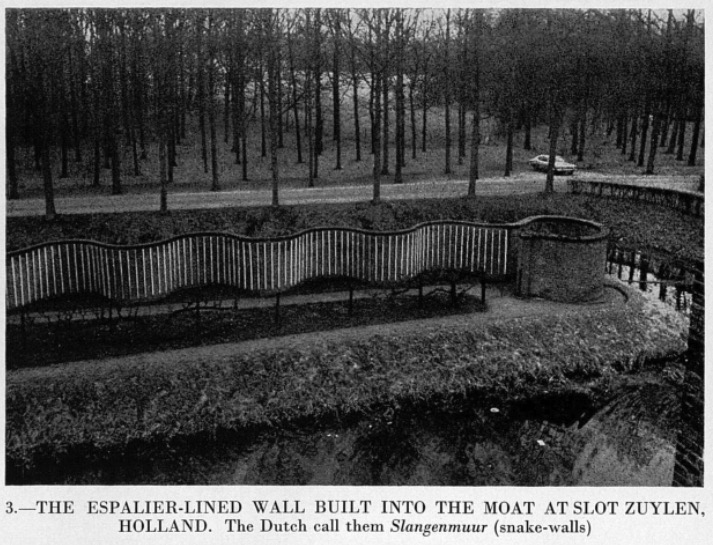

Curious Questions: What is a crinkle-crankle wall?

Curious Questions: What is a crinkle-crankle wall?The mysterious term crinkle-crankle wall is something you'll see scattered in to architecture books and even property listings. But what are crinkle-crankle walls? Why are they shaped as they are? And who first came up with the idea? Martin Fone explains all.

By Martin Fone Published

-

What it's like to live in the world's most famous crooked house

What it's like to live in the world's most famous crooked houseA few months ago this irresistibly pretty house in Lavenham, Suffolk, featured on the cover of Country Life. We caught up with Alex and Oli Khalil-Martin, the couple who own and live there, to find out what it's like living in one of the country's — and indeed the world's — most photographed homes.

By Flora Watkins Published

-

A simply stunning eco home near Henley-on-Thames that offers state of the art living in an unspoilt rural environment

A simply stunning eco home near Henley-on-Thames that offers state of the art living in an unspoilt rural environmentTraditionalists look away – or rather, don't — as we're sure Ossicles will capture the hearts (or at the very least instil a sense of admiration) of even the most die-hard anti-modernists amongst us.

By Lydia Stangroom Published

-

As woodland is booming, and planting trees has become the right thing to do — with both heart and head

As woodland is booming, and planting trees has become the right thing to do — with both heart and headInvesting in woodland has never been more popular, and the reasons are as much about sustainability as they are commercial. Carla Passino explains more.

By Carla Passino Published

-

Can we make our houses Green? The huge battle we face to make our properties fit for a carbon-neutral world

Can we make our houses Green? The huge battle we face to make our properties fit for a carbon-neutral worldDecarbonising the UK housing stock is one of the biggest challenges the country faces. Carla Passino investigates.

By Carla Passino Published

-

60 simple sustainability tips to make your home, garden and life better

60 simple sustainability tips to make your home, garden and life betterWe spoke to experts to get their tips on practical steps we can all make to live a more sustainable life in all areas of our homes and gardens.

By Country Life Published