Which birds increase your house price?

Which native birds can increase the value of your property?

My barn boasts a family of wraith-white barn owls that float overhead, swoop over the yard and quarter the fields beyond on vole patrol. The stream enjoys regular visits from a kingfisher that, bringing Bond Street to the Thames Valley, flashes his jewel-bright outfit as he trims out the modest-sized fish that seem to survive both his attentions and those of a heron and a pair of glamorous white egrets.

Similarly, the squat stone shed in the kitchen garden accommodates a wealth of birds, including two pairs of swallows, a family of wrens and a blackbird on her nest. The ruinous barn beyond is home to two fecund pairs of pied wag-tails and a pair of English partridge has given up its crow-, fox-or-I hardly dare think it-egg-hungry-labrador-ravaged nest, in favour of feeding surreptitiously in the yard like honorary chickens.

This is a partial roll call of the birds that share Ham Court, Bampton, Oxfordshire, with us. They form a self-sustaining, independent community whose all-day performance is one of the most desirable aspects of country life.

Country Life is, of course, also most desirable, not just because of its proud 116-year history as the voice of the countryside, but also because of the number of advertisements for the most sought-after rural homes it contains. Quite apart from beguiling imagery, the descriptions of alluring, come hitherish rectories, thatch-bent cottages and romantic farmhouses in temptingly manageable parcels of land-often accompanied by that enticing footnote: ‘more available by negotiation'-include a litany of attributes and key phrases that are shorthand for the dreams of the country property owner.

‘A short drive' means that we will live together in unimaginably cosy and contented privacy; ‘a productive kitchen garden' means ‘she will never make me go to Waitrose again'; ‘an orchard' means we'll lie under blossom-spattered, lichen-covered trees; and ‘a well-maintained tennis court' (or, more likely, a near-lunar surface of craters from which young sycamore trees have been hastily eradicated) promises endless visits from lissom neighbours and sum-mer afternoons filled with general contentment.

But should these be the only pointers that estate agents use? Why not ‘all three species of woodpeckers seen daily' and ‘curlew calls can be heard from bedroom three'? And, rather than the ubiquitous ‘close to Oxfordshire's well-known prep schools/Vale of the White Horse country/easy communications via Didcot Parkway', wouldn't it be better to add something along the lines of ‘the two paddocks sustain a healthy population of voles that allow barn owls to hunt every evening outside the kitchen'.

Indeed, as well as a colour chart that trumpets a property's energy-efficiency credentials, a similar spectrum could be used to illustrate the biodiversity of Church Farm, The Grange or Honeysuckle Cottage. Detailed descriptions might, in due course, even include a species list. ‘Every house buyer likes to get something for free. Frequently, we discuss carpets and curtains, but to live in sight of the regular flight line of migrating swans or geese is a thrill and it's an attribute that could almost be included in the particulars,' says Sam Gibson of Strutt & Parker. ‘Many would forego an outbuilding for such a pleasure. For me, the sound of drumming snipe in front of our house adds material value.'

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Other leading estate agents see the sense in this way of marketing a property, too. ‘As a potential buyer viewing a house, to see a barn owl quartering the ground in the meadow as you come up the drive would be a thrilling sight and would undoubtedly tune you in to the property favourably from the outset,' concurs Savills' Louis de Soissons. ‘If there's water, and you were lucky enough to see a kingfisher diving in a flash of emerald green, it would have the same effect. Swallows are homely and seem to emphasise continuity and stability. All these things tweak the senses of a buyer as they do all of us and make us more receptive.'

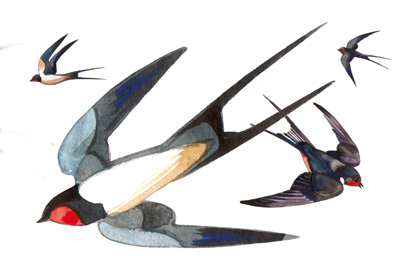

Swallow (5 points per nesting pair)

Everything has conspired against the swallow, from the tidying of outbuildings and their conversion into ubiquitous home offices, to the cataclysmic reduction of dairy farms, which has reduced both the insects they eat and the mud needed to build those perfect quarter-spherical nests, and the depredation of their numbers by hungry nations in their wintering grounds. Where once the air was filled with their summer-defining chirp and swoop, there may now only be a pair or two.

On the plus side, they're opportunistic-a new, open garage may be colonised in year one and ponds, moats and new lakes are immediately put to use by arriving hirundines each spring. Take care to avoid shutting shed doors with them on the wrong side or closing gaps unnecessarily-it might make all the difference.

Kingfisher (10 points)

Well, you need water. They actually nest in sandy river or brook banks, but will venture far afield in search of dwindling stocks of minnows and sticklebacks. Their electric-blue plumage needs no description, but the metallic chink of their call and the speedy flat trajectory of their flight are instantly recognisable if they move in. Friends in Devon left a dead tree in their lawn. Unsightly? Not with a kingfisher on it in the morning sun, as it dried off after a successful dive into the River Tor. Basically, a kingfisher repres-ents untold riches, and a fly-past on viewing day is a sale-clincher.

House martin (5 points per nesting pair)

Easily identified by their tight, forked tail, petrol-blue-black iridescent plumage and smart white rump and belly, martins are the eave dwellers that dip down in front of your bedroom. Inconceivably, they're unwelcome to some who perceive them as messy or, sillier still, noisy neighbours.

Every year, yourmartins, or their children, will return from sub-Saharan Africa to your eave. They also benefit from insect-rich grassland. Try walking through long grass on a sunny evening and watch the martins in your wake hunting the flies you've disturbed. Recently, a muddy puddle attracted nest-material-hunting martins. It dried out, but sloshing a bucket of water over it turned the mud patch back into an avian Jewson's depot.

Goldfinch (2 points)

The flash of yellow on the wing makes this bird instantly identifiable and the red face, symbolic of a progenitor finch, whose face was splashed with the blood of Christ as it drew a thorn from his crown,explains his association with the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The goldfinch's Latin name, Carduelis carduelis, tells the tale.They're thistle eaters, so if you leave thistles to flower, and set their powder-puff seedheads, they'll attract chattering flocks of finches (a group is called a charm-nice, eh?), which means there's a decision to be made. Are thistles unsightly and pernicious or are they part of the picture glittering with finches? Leaving the edge of a field or a corner uncut could be all it takes.

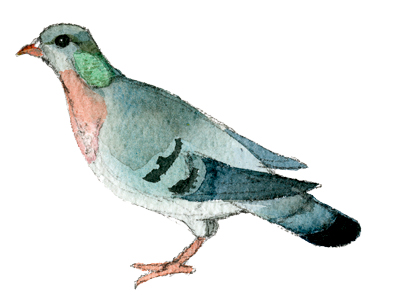

Stock dove (5 points per nesting bird)

These are the quieter, speedier and rarer cousins of the wood pigeon, modest in nun-like grey and missing the tell-tale white wing bar of their cabbage-raiding relations, stock doves love a barn, even a plain tin Dutch one. They make a rather messy stick nest on a ledge and then flip quickly away on fast wingbeats whenever you approach.

Their food sources aren't a problem-the thousands of acres of oilseed rape that cover lowland Britain sustain them through the hardest winter-but it's nest sites that are at a premium. Not a showy bird, but a quintessential bit-part player in the rural landscape.

Egret (10 points)

These were a distinct rarity 20 years ago, confined to the South-West or to lost visitors along southern or eastern coasts. Now, they're an established species, nesting in heronries in trees and feeding in marsh or river sides.

They're redolent of abroad. Their newness means that many of us are more likely to have seen them in Africa, Florida or on the Venetian lagoon than on the Norfolk coast or, indeed, the Home Counties.

A pair diligently hunts our stream. When disturbed, they fly upwards, trailing their long yellow legs in a balletic pose. I saw them scoping out a disused slurry lagoon when i first viewed the house and it def-initely swayed me.

Barn owl (20 points)

The obvious feather in your cap, ghost-white and with a natural history completely linked with our own, the barn owl has benefited from traditional farm buildings and from arable farming's rich by-product of well-fed field voles, mice and other mammals.

In recent decades, high property values have massively reduced potential nesting sites as countless barns now house humans rather than hay, but the owls are adaptable and appreciative of efforts such as the installation of owl boxes and barn doors being left open.

More significant is the supply of food: permanent hay meadows and wide hedges provide the environment for the prey they need to swoop soundlessly down on. Poultry keeping is also good, because corn attracts mice and owls love mice, so your yard is bound to become an important hunting ground. One pair and their young would be good for every farmhouse, old rectory or manse.

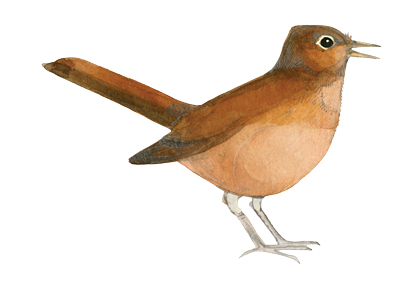

Nightingale (20 points)

Isn't this the Holy Grail of filling your garden with birds? That unforgettable noise, far from limited to nocturnal broadcasts, is the Nirvana we all need. This is the most uninteresting of birds to look at: a reddish-brown, little thrush-like person that is, even if you tempt the migratory Caruso to your property, rarely seen.

However, when they throw their feathered shoulders back and let rip with their song, they're the most magical of birds. They can also be encouraged to move into your garden: deep thorn thickets, hawthorn and blackthorn make a safe territory for them to breed in, and the chorus, in late May, is the reward.

* Follow Country Life magazine on Twitter

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country Life

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country LifeWe take a look at some of the best houses to come to the market via Country Life in the past week.

By Toby Keel

-

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwards

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwardsCampaigners in England often point to Scotland as an example of how brilliantly Right to Roam works, but it's not all it's cracked up to be, says Patrick Galbraith.

By Patrick Galbraith