The battle for landscape

Our country house architecture expert takes a look at some of the fascinating stories around country houses and their views, and surrounding landscapes

‘A brighter, richer landscape lies display'd': the battles for the views of country houses

View of the Thames from Richmond Hill' by Peter Tillemans c.1720-1723 (Image: Government Art Collection)

Looking out from the top of Richmond Hill in south west London, towards Windsor Castle, is to take in one of the most famous and admired views of the Thames. It also includes the beautiful Marble Hill House, which was also the site of a heritage battle to protect the house and that spectacular view - but it was not the first fight, as conservation has had always had to stand its ground.

The first ‘battle' to be fought to protect a heritage asset which formed part of a view was between a duchess and her husband's architect, and involved one of grandest houses in the country. Ironically, the battleground was a house built to celebrate a military victory, Blenheim Palace, but a fight almost as vicious was being waged between Sarah, 1st Duchess of Marlborough, and the architect, Sir John Vanbrugh (b.1664 - d.1726), one of the most remarkable men of that era.

Blenheim Palace

Specifically, the battle was fought over the ruins of the original Woodstock Manor, a house where King Henry II had romanced ‘fair Rosamund' de Clifford, and which formed the original palace on the estate. Having suffered under bombardment in the Civil War, large parts were in ruins. However, Vanbrugh saw them not only as a historical artefact, but also as part of the grand conception of the landscaping; a precocious attempt at the Picturesque twenty-five years before William Gilpin conceived it. Vanbrugh appealed to the Duchess but it was in vain and the house razed to the ground in 1720.

A later landmark in the campaign for heritage protection of landscape was in the early 1900s around the now-lost mansion of Witley Park in Surrey and its owner, Whitaker Wright. A controversial financier, he made a fortune, lost a fortune, made another fortune and then bought the Witley Park estate and neighbouring land which included Hindhead Common and the famous Devil's Punch Bowl. To ‘improve' the views from the house, Wright set 600 men to work, creating lakes and parkland but more worryingly, raising or levelling hills, creating a real concern that Wright's grandiose schemes would irreparably alter the local landscape.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Fortunately Wright's other fanciful plans were his undoing; following the collapse of his companies in 1900 he was charged with fraud, found guilty, and dramatically committed suicide in court just after his sentencing hearing. With his death the estate was put up for auction, and the locals who had been concerned about his landscaping efforts banded together and bought the sections of the estate which included the Devil's Punch Bowl and Hindhead Common at auction in 1905. The locals then donated the land to the National Trust in 1906, becoming, in the process, the first Trust property to be managed by a local committee.

The idea that threats to heritage such as development were a national issue for the public good strengthened as organisations such as the National Trust and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings took up the cause - and Marble Hill House was a prime example.

Marble Hill House, Surrey (Image: Maxwell Hamilton via Flickr)

Regarded as one of the finest Palladian villas in the country, the house was built between 1724-29 for Henrietta Howard, Countess of Suffolk and former mistress of George II. On her retirement from court, Lady Suffolk created a new literary, political, and artistic one, centred around her and her villa. The bright-white house was an obvious reference point for those looking down from Richmond Hill and formed ‘this Earthly Elysium‘, appreciated by those without and within.

As Richmond and Twickenham grew as one of the most fashionable places to visit, so too did the number of artists who recorded the view. Yet, the rural nature of the suburb which had so impressed those who gazed upon it became increasingly threatened as Victorian London moved west. With the death of the last owner, the widow of General Peel, in 1887, the house was increasingly viewed with avaricious eyes by developers. In 1901, a local newspaper quoted Jonathan Swift's 1727 poem ‘Pastoral Dialogue between Richmond Lodge and Marble Hill‘:

Some South Sea broker from the City Will purchase me, and more's the pity, Lay all my fine plantations waste To fit them to his vulgar taste.

The article carried on to warn that ‘It is the demon builder who will in all probability destroy this historical desmesne with his exhibition of latter day villadom‘. That threat took a more concrete form that same year when, having been empty for ten years, it was finally sold to William Cunard (of the shipping family) who lived in nearby Orleans House (dem. 1926). His plans involved the villa becoming the centrepiece to a suburban development. However, the prospect of this view being lost galvanised public opinion, causing Cunard to pause. The Architectural Review highlighted that with regards to the view:

‘...it is evident that the deep wedge of woodland formed by Marble Hill is its most necessary and indispensable part; that spoiled, the view tumbles to pieces, with an eyesore for its focus.'

Tattershall Castle, Lincolnshire (Image: Richard Croft via geograph)

In July 1901, the Richmond Hill View Executive Committee was formed and, with continued interest from the press, kept up the pressure until in June 1902, following an Act of Parliament, the house was saved. Following the Marble Hill victory, further action such as in the Tattershall Castle controversy in 1910 showed that it was possible to mount an effective opposition. Although not strong enough to prevent the worst excesses of the mass destruction of the country houses in the 1920s, 30s and 50s, these victories were critical in providing a cultural foundation, bolstered by wider appreciation through magazines such as Country Life, for the heritage protection movement which, despite many successes, continues to fight those battles today.

For the unabridged version of this article, featuring more houses and detail, please read: ‘A brighter, richer landscape lies display'd'; the battles for the views of country houses' Matthew Beckett writes about the UK's wonderful country houses at ‘The Country Seat' and also on twitter @thecountryseat. He also writes and researches about the hundreds of lost country houses at ‘Lost Heritage - a memorial to demolished English country houses'.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Mary Greene Published

-

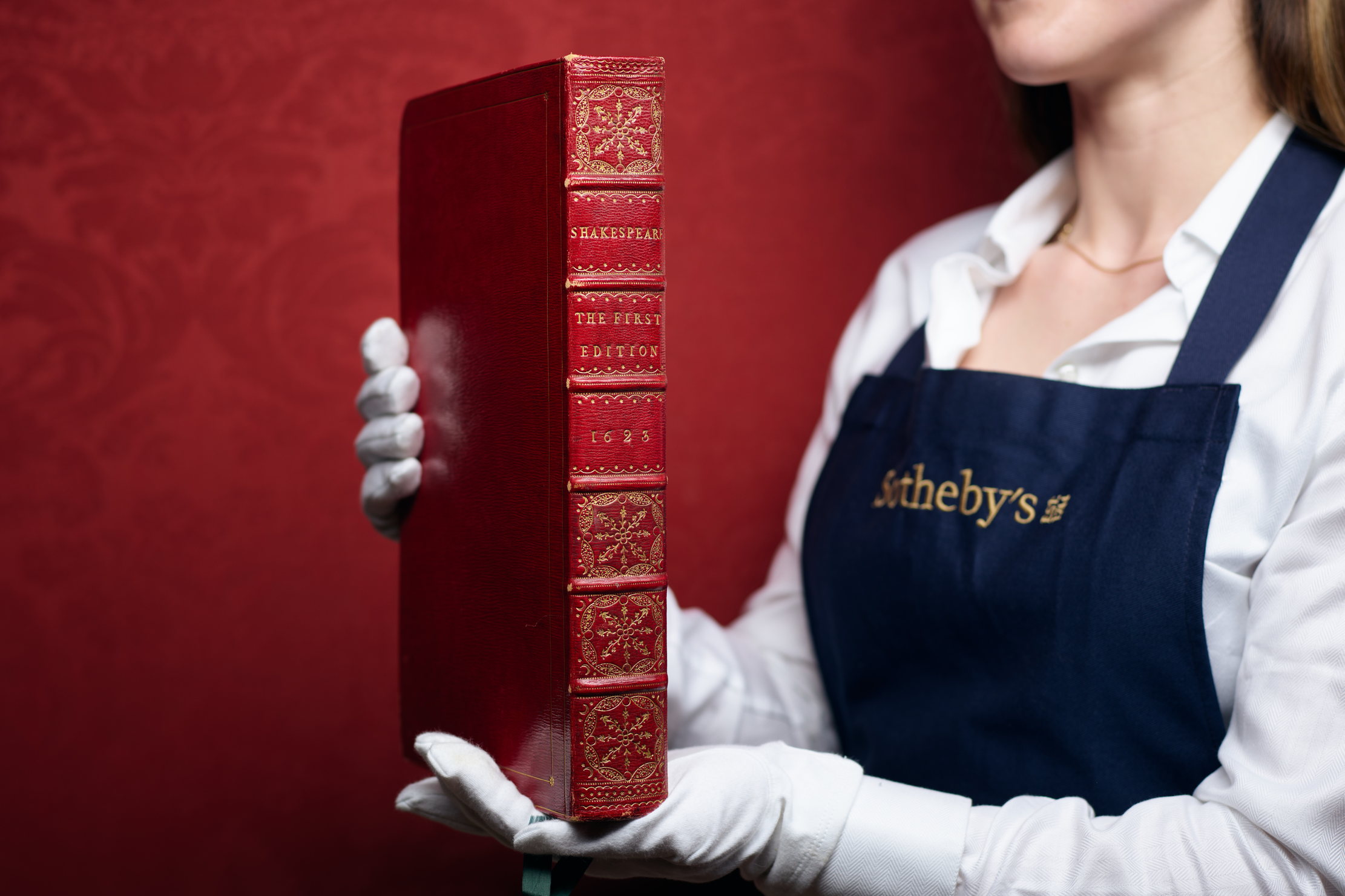

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle Published