Barnes: The London village encircled by the Thames that's left an indelible mark on the nation

Barnes played a role in everything from the invention of football to the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. Carla Passino takes a closer look.

Until an army of 19th-century engineers descended on Barnes to build bridges and railways, this was a world apart, a rural idyll preserved intact by the Thames that bounds it on three sides.

Mentioned in the Domesday Book, the village had made history even earlier, when it was granted by King Æthelstan to the canons of St Paul in the 900s. The link between Barnes and St Paul’s persists more than 1,000 years on, as the Dean and Chapter owns one of the local gems: 122-acre Barnes Common.

Today, its woodland and acid grass-land are an oasis for hedgehogs, bats, butterflies and Nature-starved Londoners, but, for many centuries, they were home to grazing cattle. The livestock even became embroiled in a dispute between Barnes and neighbouring Putney in 1589, when ‘the men of Barnes refused to allow the men of Putney to use the Common and impounded their cattle,’ reports A History of the County of Surrey.

By the time of this falling out, the Church of St Mary’s, Barnes’s oldest building, had been standing for 400 years and had received a distinguished visitor: Stephen Langton. ‘The Archbishop stopped overnight on the way back from Runnymede, having sealed Magna Carta,’ says Paul Rawkins of the Barnes and Mortlake History Society. Although the Grade II*-listed church no longer looks like the one Langton reconsecrated in 1215, the oldest portion of it is now named the Langton Chapel.

Medieval Barnes’s other landmark, the Barn Elms manor house, has long been demolished, but not before playing host to a sequence of prominent figures, from 15th-century House of Commons speaker Sir John Say to Elizabeth I’s spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham. ‘It is said that the order to execute Mary Queen of Scots was dispatched from Barn Elms,’ notes Mr Rawkins.

The arrival of Handel, who spent some time in Barnes in 1713, marked the beginning of a rich musical history that continues to this day, encompassing composers such as Gustav Holst, Herbert Howells and, more recently, Carl Davis, Howard Goodall and Roxanna Panufnik. Above all, Barnes saw the history of rock forged at its legendary Olympic Studios, where The Rolling Stones, Queen and Led Zeppelin all recorded songs.

Saved from development, the Olympic is now a cinema and may soon see the opening of a new recording studio. Until then, there is always The Bulls Head to fly the flag for music: specialising in jazz, the pub, which in 2007 hosted an impromptu performance by Mick Jagger, is SW13’s answer to Ronnie Scott’s.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Equally strong are the village’s literary connections, ever since Henry Fielding moved to the Green’s Milbourne House in about 1750 and Charles Dickens spent part of his summers at The Terrace, a row of impossibly pretty Georgian homes facing the Thames.

Perhaps Barnes’s longest-standing resident writer was the late Judith Kerr, who lived in the same home for 57 years (her kitchen bore a striking resemblance to the one in her The Tiger That Came To Tea). Fittingly, the village runs one of the UK’s largest children’s book festivals.

Barnes is closely identified with the Arts, but sport is also an integral part of its heritage. As well as being a vantage point for the Boat Race, the village was the cradle of British football. In 1863, Ebenezer Morley drafted the Football Association’s first rules at 26, Barnes Terrace — including the provision ‘no player shall wear projecting nails’ — and pioneered the new system at his Barnes Football Club.

Many of the team’s matches took place at the Barn Elms playing fields, under the watchful eye of a plane tree that had been planted in the 1680s and still stands — the oldest and, at 27ft in girth, the largest plane in London.

On the opposite side of the fields is another of the village’s great open spaces: the WWT London Wetland Centre. Past its gates, London recedes to a vague outline on the horizon, replaced by a mosaic of lakes, meadows, marshes and lagoons, where otters roll in the mud, water pipits hunt for insects and bitterns peek from among the reeds. ‘Each season, we have different wildlife,’ reveals the centre’s Angelica Teixera.

With more than 100 acres of land and a vast range of habitats, the reserve is a triumph of biodiversity — one that needs constant maintenance, but, she explains: ‘Luckily, we have an army of volunteers, many of whom live in Barnes.’

The public’s involvement is testament to Barnes’s greatest charm: its community spirit. Not only does the village have a packed calendar, from the weekly Farmers’ Market to the annual Barnes Fair, plus an excellent local newsagents in Natsons, but, says town manager Emma Robinson, residents are ready to work on local projects.

‘There is a strong community that feels the village atmosphere should be retained,’ agrees Mr Rawkins.

‘When people move to Barnes, they tend not to move again, so, once here, you have a vested interest in making sure it remains as it is.’

This article appears in the London Life section of Country Life on January 6, 2021.

Barnes highlights

Orange Pekoe One of London’s prettiest afternoon tea places. 3, White Hart Lane — www.orangepekoeteas.com

Two Peas in a Pod A traditional greengrocer with a name that’s hard to beat. 85, Church Road — Website

Barnes Fish Shop The fish is fresh from Cornwall. 18, Barnes High Street — Barnes Fish Shop Facebook page

Church Road Barnes has plenty of great restaurants, but this new opening is already a favourite. 92–94, Church Road — www.churchroadsw13.co.uk

Tobias and The Angel A treasure trove of furniture, antiques and hand-block textiles. 68, White Hart Lane — www.tobiasandtheangel.com

Hackney's journey from bucolic open space to one of London's great melting pots: 'It's the friendliest place I know in London'

Over the centuries Hackney has morphed from a land of gardens and streams to a vibrant, artsy and welcoming community,

The story of Old London Bridge, the iconic landmark which vanished from the capital's skyline

Important new discoveries illuminate the form and history of the houses that lined one of London’s most celebrated lost landmarks.

Toby Keel is Country Life's Digital Director, and has been running the website and social media channels since 2016. A former sports journalist, he writes about property, cars, lifestyle, travel, nature.

-

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?The team behind London's first mixed-use ‘wellness village’ says it has the magic formula for tempting workers back into offices.

By Annunciata Elwes Published

-

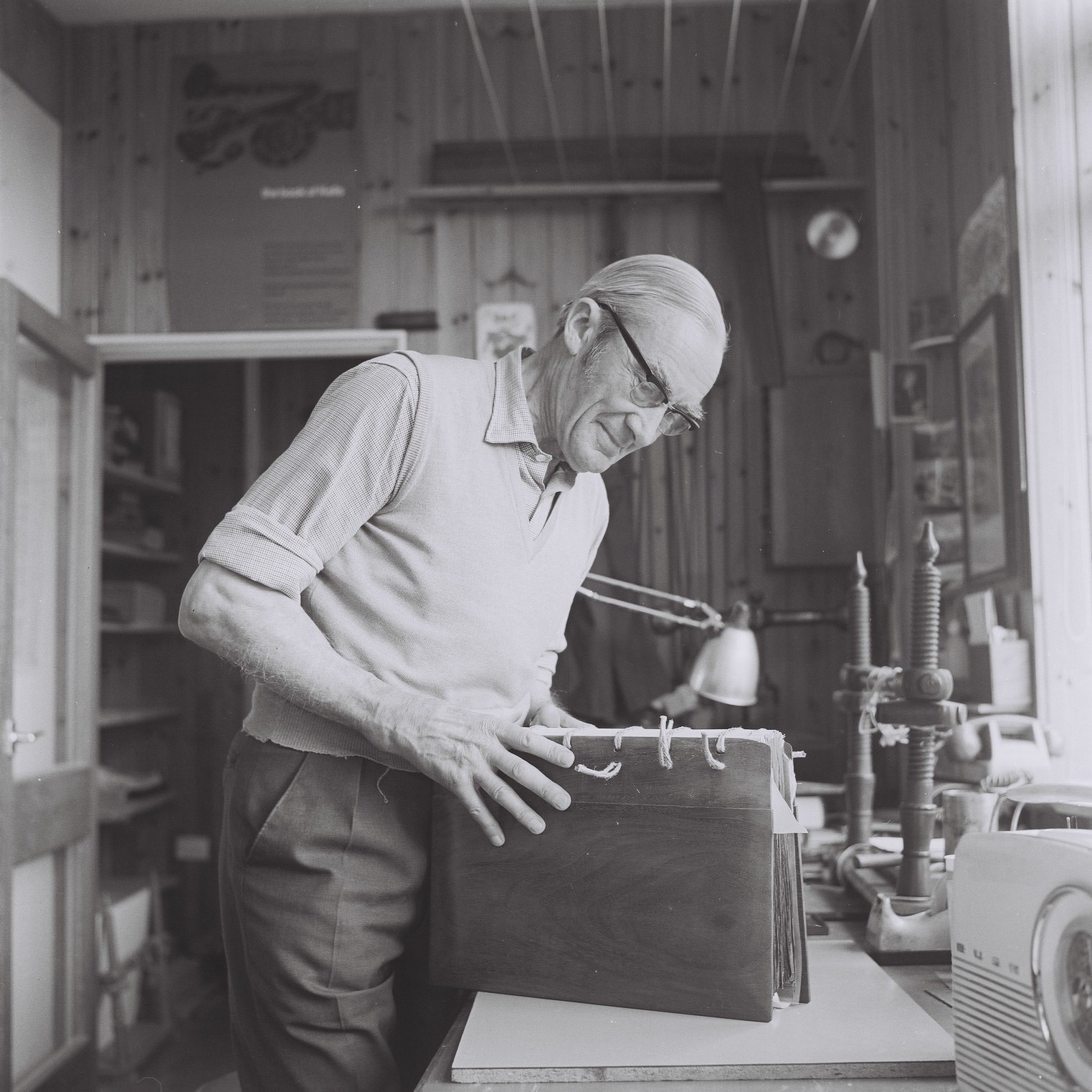

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani Published

-

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?The team behind London's first mixed-use ‘wellness village’ says it has the magic formula for tempting workers back into offices.

By Annunciata Elwes Published

-

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'The Paper Mill estate is a picture-postcard in the Garden of England.

By Penny Churchill Published

-

Hidden excellence in a £7.5 million north London home

Hidden excellence in a £7.5 million north London homeBehind the traditional façades of Provost Road, you will find something very special.

By James Fisher Published

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher Published

-

A Grecian masterpiece that might be one of the nation's finest homes comes up for sale in Kent

A Grecian masterpiece that might be one of the nation's finest homes comes up for sale in KentGrade I-listed Holwood House sits in 40 acres of private parkland just 15 miles from central London. It is spectacular.

By Penny Churchill Published

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher Published

-

Could Gruber's Antiques from Paddington 2 be your new Notting Hill home?

Could Gruber's Antiques from Paddington 2 be your new Notting Hill home?It was the home of Mr Gruber and his antiques in the film, but in the real world, Alice's Antiques could be yours.

By James Fisher Published

-

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?The King's recent visit to Nansledan with the Prime Minister gives us a clue as to Labour's plans, but what are the benefits of traditional architecture? And can they solve a housing crisis?

By Lucy Denton Published