The solution to the second home problem? A charter that would ensure second home-owners enrich and support communities

Simon Jenkins — himself a second home owner — tackles the thorny problem of second home ownership, which hits 70% in some parts of the country.

Edward Hudson founded Country Life in 1897, it was to celebrate ‘the search for beauty’ that was a city dweller’s ideal of rural England. It would open new horizons to urbanites adventuring forth in their new motor cars. A lucky few might even be enticed to go further, to find a second home in the bosom of Nature, the legendary ‘place in the country’.

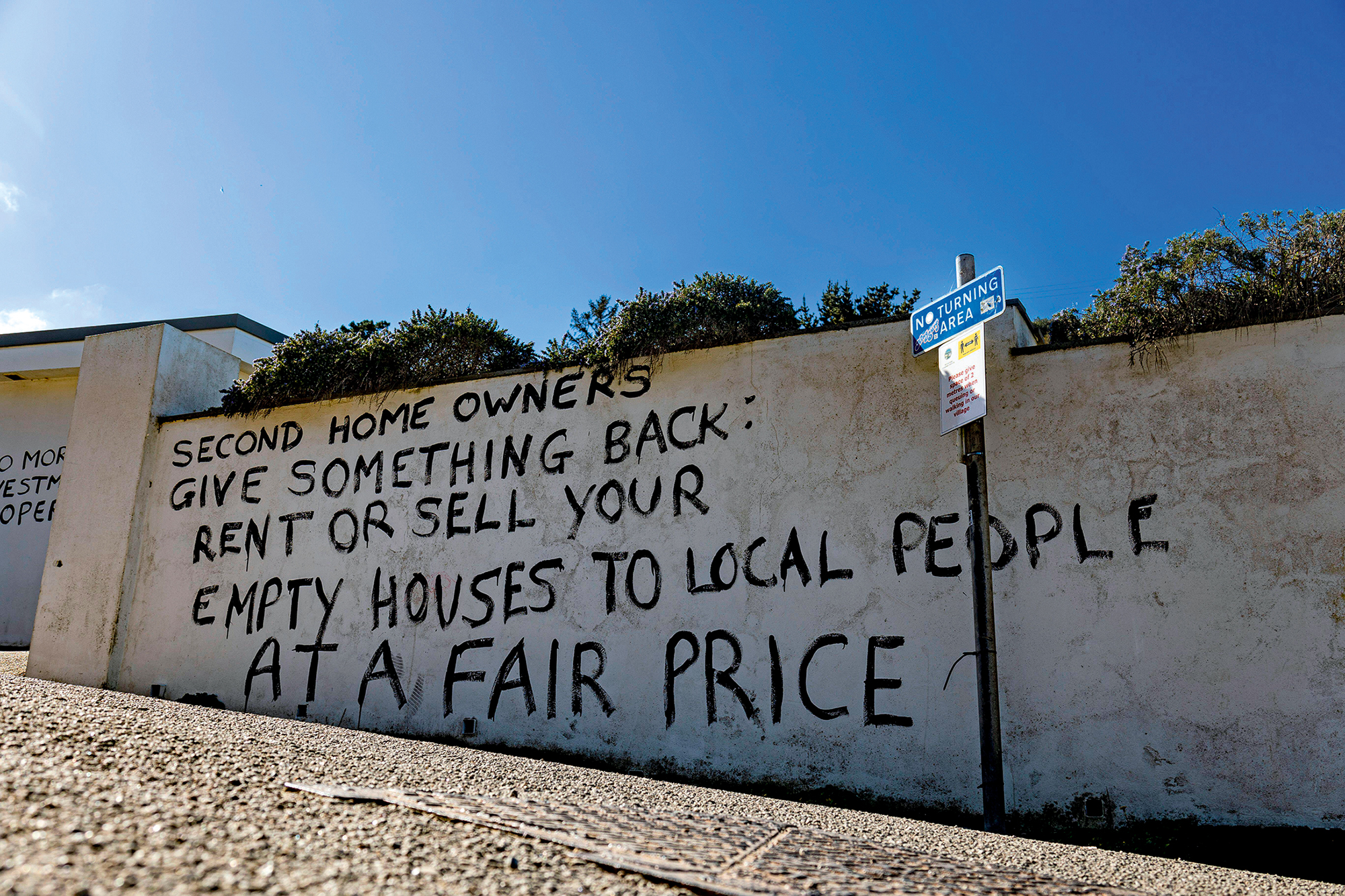

Today, that place is turning sour. Before the recent pandemic, it was estimated that half a million families had second homes somewhere in Britain. This might be only 2% of the housing stock, but it has surged in coastal and upland beauty spots, often to more than 70%. House prices are inflated and communities eroded. Streets lie empty for much of the year. Protests are heard from Cornwall to north Wales, from the Lake District to the Yorkshire coast.

Hostility has gone political. Cornwall has prepared to double council tax on second homes and others have followed suit. The Welsh government now allows councils to levy a tripled surcharge on such homes, which could push top bands to £18,000 a year. St Ives demands that all new houses be confined to full-time residents. South Hams requires that titles be registered as for ‘principal residences’ in perpetuity.

All say the same thing: Keep Out.

Traditional holiday resorts have long profited from their appeal to outsiders. Scarborough, Blackpool and Torquay are used to seasonal migrations and to properties being empty much of the year. It is the price they pay for their principal business, tourism. Much of the current hostility comes from smaller towns and villages hit by a decline in fishing and agriculture and facing desertion by their young leaving to work in cities. An LSE study of St Ives may conclude that its new restrictions ‘hit tourism and construction’, but yield no noticeable benefit to locals. But the hostility remains intense.

Long-established rural communities are famously tight knit and averse to outsiders. From France’s Manon des Sources to Suffolk’s Akenfield, they instinctively resist intrusion. But what was gradual has become a torrent. Working from home, ‘staycationing’ and Brexit’s obstacles to second homes in France have seen a shift in how the better off spend their money. They feel it unfair to be denied a retreat from a hard-working week in the city, just as it is unfair on locals to be denied the open-market price for their property. It may be reducing the availability of housing for long-term rent, but that is happening everywhere. Beautiful villages are becoming like very expensive parts of towns.

Where argument becomes more trenchant is over the impact of newcomers on community cohesion. Here, there seems to be a crucial difference. Terraces of boarding houses, holiday lets and Airbnbs cater for tourists, anonymous comers and goers who have no contact other than the commercial with local people. Second homers, on the other hand, can develop a strong local commitment to their alternative residence. They have invested by choice in a particular place, either through some family link or through having holidayed there in the past. They frequently stay on in retirement or become ‘first homers’, with the city as their second one.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

"Those who devote money and time not to vanishing overseas but to celebrating the glories of rural Britain should not be hounded back into cities. They should be welcomed as allies in a joint cause"

A local friend where I have a second home once told me: ‘I much prefer to have neighbours who appreciate living here, rather than my children who so desperately want to leave.’ Second homers bring new money and sometimes new businesses to what might otherwise be declining parts of the country.

They concern themselves with local issues and contribute to local causes. One such was the science writer John Maddox, who stood as ‘second home’ candidate for his local council in Brecon and even secured election. In parts of the Continent, such as Portugal and Sicily, second homers are subsidised by the state to restore property in emptying and isolated places.

I am sure there is a compromise. Second homes are not going away. But at least their owners can do something to acknowledge what their presence — and frequent absence — does to an established community.

One solution would be a voluntary second-homes charter, drawn up by councils and offered to all newcomers.

They would pledge always to use local shops and employ local services.

They should try to keep their properties occupied as much as possible, if not by themselves, then by family, friends and others.

They will respect local traditions and support local clubs and charities.

They will understand that these communities are composed of people, not merely nice buildings and nice views.

In 2000, ‘the countryside’ ranked with the Royal Family and Shakespeare in millennium polls of the ‘most treasured features’ of Britishness. Recent planning reforms, mooted and enacted, have put the rural landscape at severe risk of degradation. Casual swerves in policy on farming, Nature conservation, renewable energy and rural housing have become ever more alarming. Campaigning for the beauty of the countryside is even dismissed by philistines as the preserve of anti-growth nimbys.

Second homers are often in the front line of that campaign. Those people who devote their money and their spare time not to vanishing overseas but to celebrating the glories of rural Britain should not be hounded back into cities. They should be welcomed as allies in a joint cause. The countryside needs new blood, as well as old, in the fight for Hudson’s great cause.

Simon Jenkins is a journalist and author who began his career at Country Life before going on to serve as the political editor of The Economist and editor of The Times.