From California to Cornwall: How surfing became a cornerstone of Cornish culture

A new exhibition at National Maritime Museum Cornwall celebrates a century of surf culture and reveals how the county became a global leader in surf innovation and conservation.

Wave riding has been a cornerstone of Cornish culture since locals first took to the sea on prone wooden boards (nicknamed ‘coffin lid boards’) in the 1920s. Stand-up surfing arrived by way of Australia and America in the 1950s, transforming Fistral Beach into the surf Mecca it remains today. Over the decades, trends have shifted from shortboards back to longboards, para surfing has taken off, and what was once thought to be a male-dominated sport is now much more inclusive — with world-renowned surfers including Lucy Campbell and Charlotte Banfield learning to surf on south-west waves.

This week, the National Maritime Museum Cornwall's (NMMC) exhibition celebrating Cornish surfing opened. SURF! 100 Years of Surf Riding in Cornwall has been curated by writer, filmmaker and former European Longboard Champion Sam Bleakley, who has explored how the UK has become a global centre point for surf innovation and activism. ‘It means a lot to me to take surf narratives and the positive impact of surfing in Cornwall to a wider audience,’ he muses.

‘The Bilbo shop is a really fantastic highlight,’ Bleakley states, detailing the recreation of the iconic Newquay-based surf brand that formed in the mid-60’s. Legendary photographer and one of Bilbo’s founders, Doug Wilson’s iconic trumpet (‘he used to play to signal the end of his lifeguard shift’) and a selection of his cameras are on display. Alongside an evolutionary timeline of Cornish surfboards, Abigail Fallis’s poignant Plastic Waves sculpture and Maia Norman’s collection of boards decorated by Damien Hirst, Bleakley’s other personal highlight is the display of Chris Jones’s tools, equipment and boards. ‘Chris was a significant Cornish surfboard builder and European champion,’ he explains. ‘He had a big impact on my life in the sense that I used to get my first surfboards from him and he went to school with my dad. He was one of the best surfboard craftspeople Europe has ever seen.’

Bleakley’s dad, incidentally, was who first got him into surfing as a child. ‘My dad was one of the first generation of local kids getting into stand-up surfing in the 1960’s. His Dad ran a B&B that had a bar on Headland Road at Fistral. A lot of the Australian lifeguards used to drink in that bar — one of them owed my grandad some money from games of poker, and he paid that debt via a surfboard that my grandad gave to my dad for his birthday.’

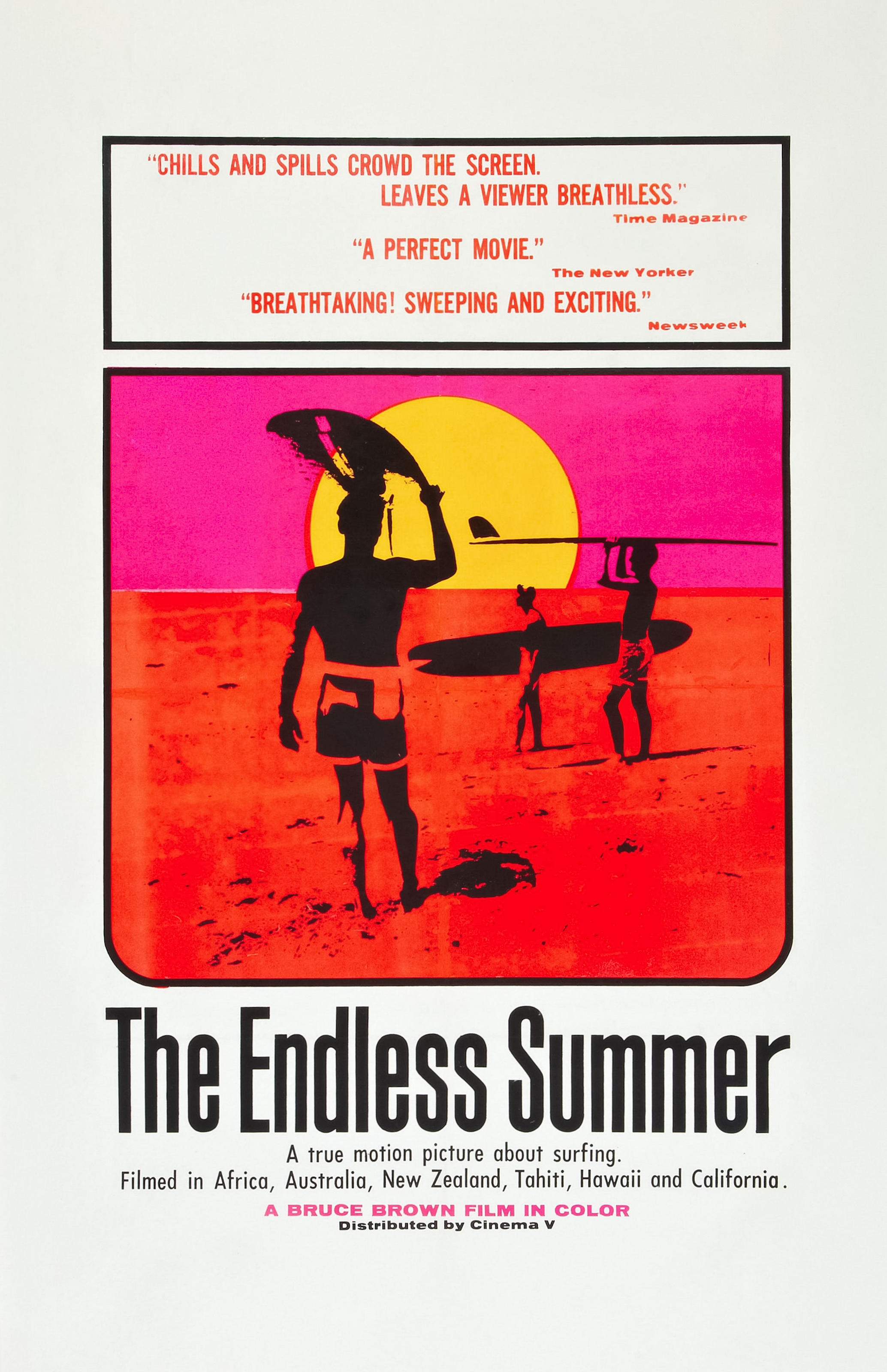

The critically acclaimed film followed two surfers around the world in search of the best waves.

Following the Second World War, and with the introduction of commercial air travel, Australian and American surfers began travelling the world in search of waves to ride. This journey brought many of them to Cornwall, specifically Newquay, where their innovative boards and stand-up surfing skills caught the eyes of locals like Sam’s dad who had been prone-boarding for decades. Bands like The Beach Boys and films like The Endless Summer helped to bring surf culture into the mainstream.

But why Cornwall? Its position in the Atlantic, its 422 miles of coastline and the topography of the seabed all combine to create reliable surf conditions for both beginner and pro surfers. ‘We’re blessed with this large variety of wide open sandy beaches with rocky headlands,’ explains Bleakley. ‘Those beaches are very well exposed to consistent surf from the Atlantic. We have a long continental shelf that extends a fair distance out from the Cornish peninsula, and that takes the sting out of the power of the stormy surf, creating very gently rolling waves on our soft, sandy beaches.’ Sam goes on to discuss how these waves were well suited to prone riders in the 1920s and the first stand-up surfers in the 1950s and 60s, but when surfboards got shorter in the 1970s, adventurous surfers took to riding more powerful winter waves in destinations like Porthleven — where the waves break violently over a shallow rock reef.

Campbell (above), the seven-time Women’s National Surfing Champion, began her surfing journey in the early 2000s after moving to the coast of North Devon at five years old. She’s surfed all around the world from Indonesia to Australia, but believes British surfers are some of the most dedicated and hardy. ‘You really have to love it to stand in a carpark getting changed when it's -2 degrees and sleet is coming in sideways. But there is something so invigorating about being out there all cosy and warm in your wetsuit against the elements.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Rain or shine, the Cornish coast lures surfers to its shores with the surfing industry now worth more than £153 million every year (ITV News, 2023). Newquay has been the UK’s surfing capital since the 1960’s — and accessibility to the sport has evolved with everything from surf and yoga retreats to surf schools and calendar-highlight Boardmasters Festival now on offer. There’s also a big push to use surfing therapeutically, as pioneered in Cornwall by The Wave Project, who provide a space for young people to explore surf therapy alongside accessible surfing programmes.

Mawgan Porth beach with Newquay just visible in the background.

Further along the coast, Watergate Bay and Scarlet hotels arrange surf lessons alongside spa treatments. The latter, perched above Mawgan Porth with its metronomic, rolling waves, partners with King Surf School and local legend, Pete. ‘We believe in creating a harmonious balance between adventure and relaxation,’ comments the hotel’s marketing manager, Robyn Pound-Woods.

Fistral Beach and the surrounding northern Cornish coastline may be the Bondi of Britain, but you can catch a wave all around the south-west peninsula. Bleakley grew up surfing with his family at Sennen Cove, and there are reliable waves everywhere from Polzeath, moving anticlockwise, to Praa Sands. Bleakley now surfs with his own children — their Grandfather still riding the waves beside them. He speaks on the importance of raising children to respect coastal environments. Pollution from raw sewage flowing free into the ocean and ever-growing plastic contamination is a hot topic with everyone you speak to.

Campbell knows all about the impact of pollution in our coastal waters: ‘I witness changes firsthand, whether that’s algae blooms in the water, microplastics, or massive shifts in sand caused by construction close to the coast. And I’ve been sick countless times from poor water quality.’

A thought-provoking Surfers Against Sewage campaign poster image.

Surfers Against Sewage (SAS) are leading the charge when it comes to protecting our shores. James Luxton, SAS’s head of communities, explains the link between surfers and coastal conservation: ‘To want to protect something you have to know it and to fight for it you’ve got to love it. When you are surfing, you are inherently connected to and reliant upon the environment you’re in. We talk about “from the beach front to the front benches of parliament”, bringing together all this energy and anger…that’s how change comes about.’

One innovative change that Luxton talks about in detail is the momentum for alternatives to Neoprene wetsuits. Traditional wetsuit components are mostly made in a single Louisiana-based factory which is the focus of The Big Sea, a new documentary, by Cornish filmmakers. In it, we discover that the community living in the shadow of this factory have 50-times the national average risk of developing some kind of cancer. ‘The alternative is Yulex, which is natural rubber. Next door to us is Finisterre [and with] Patagonia [they] are leading the charge in terms of Yulex wetsuits. C-Skins has just released their Yulex range.’

‘I think there’s an opportunity for the surf industry to be real pioneers in environmental movements,’ says James Otter, founder of his eponymous wooden surfboard brand. Otter’s hand-crafted boards are designed to last a lifetime; conceived when he was studying furniture design and riding boards in his spare time that were always falling apart. Alongside ready-to-ride boards, Otter also offers hands-on workshop experiences. When asked if sales have been increasing, Otter chuckles: ‘We kind of shoot ourselves in the foot because we make surf boards designed to last so long that we don’t tend to get repeat custom.’

So, what will Cornwall’s surf scene look like in another 100 years? Hopefully, even more sustainability-focused innovations, plus crystalline waves empty of sewage and plastics, but whatever happens, wave riders will still flock to Cornwall’s shores. ‘Surfing is never going to lose popularity; there’s something about it that will always be seen as cool and fun. I often think it’s like adult play…it’s one of the spaces where you’re allowed to be a kid again,’ concludes Otter.

Based in the Yorkshire countryside, Emma is a travel and lifestyle writer, who also works as a travel, hotel and Nature photographer. She's wrote for Small Luxury Hotels, The Luminaire, Blumenhaus magazine, Lodestars Anthology and Staays.

-

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric villageA romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

By Ben Lerwill

-

Never leave a bun behind: What to do with leftover hot cross buns

Never leave a bun behind: What to do with leftover hot cross bunsWhere did hot cross buns originate from — and what can do with any leftover ones?

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passions

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passionsVincent Zanardi reveals the present from his grandfather that he'd never sell and his most memorable meal.

By Rosie Paterson

-

‘Large Welsh choirs have long been an obsession’: Accessories designer and ‘Sunday Times’ bestselling author Anya Hindmarch’s consuming passions

‘Large Welsh choirs have long been an obsession’: Accessories designer and ‘Sunday Times’ bestselling author Anya Hindmarch’s consuming passionsAnya Hindmarch reveals what gets her up in the morning, who her aesthetic hero is and the hotel she could go back and back to (sort of).

By Rosie Paterson

-

The Ravenna Palazzo where Byron lived and loved is now a museum dedicated to his memory — and it's just been toured by Queen Camilla

The Ravenna Palazzo where Byron lived and loved is now a museum dedicated to his memory — and it's just been toured by Queen CamillaOn a Royal State Visit that coincided with her wedding anniversary to His Majesty King, the Queen found a moment to tour a newly reopened museum devoted to the Romantic poet.

By Carla Passino

-

Good things come in threes: Sir Cecil Beaton's love of flowers, fashion and fabulous friends in a trio of exhibitions

Good things come in threes: Sir Cecil Beaton's love of flowers, fashion and fabulous friends in a trio of exhibitionsIt’s been 45 years since Sir Cecil Beaton died, but he has inspired not one, not two, but three new exhibitions this year.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Film star, resistance fighter and civil rights activist: The life and times of Josephine Baker, 50 years on from her death

Film star, resistance fighter and civil rights activist: The life and times of Josephine Baker, 50 years on from her deathJosephine Baker was an American-born actress and dancer, who would go on to take France by storm and become one of Europe’s highest-paid performers. She also happened to be a Second World War spy.

By Amy Serafin

-

Meet the willow weaving artist whose work is popular on both sides of the pond

Meet the willow weaving artist whose work is popular on both sides of the pondThis summer, Laura Ellen Bacon's work stars in two different exhibitions.

By Carla Passino

-

Chloe Dalton: The woman who swapped top-level geopolitics to rescue a baby hare

Chloe Dalton: The woman who swapped top-level geopolitics to rescue a baby hareAs an expert foreign policy adviser, Chloe Dalton's life revolved around international travel and walking the corridors of power. Then a chance encounter while out on a walk changed her life forever.

By Toby Keel

-

Constance Spry, Harry Styles and rescue dogs: Florist and founder of the Wild at Heart Foundation Nikki Tibbles’s consuming passions

Constance Spry, Harry Styles and rescue dogs: Florist and founder of the Wild at Heart Foundation Nikki Tibbles’s consuming passionsNikki Tibbles reveals the possession she would never sell and who would play her in a film.

By Rosie Paterson