Prophet, playboy, and provocateur: How meeting Peter Beard changed my life

Peter Beard's dramatic, bloody artwork and drug-fuelled partying might've shocked American society, but is was 'desperately important' to his biographer who recounts meeting him, aged 78, at the artist and diarist's Montauk home.

What did I know of the late artist and photographer Peter Beard when I met him in 2016, I wonder? Just the legend, I expect, just the spectacular image he had so carefully created and projected into pop culture, of the 20th century Tarzan, at one with the birds and the beasts, a party animal swarmed under by supermodels, rock stars and the rest.

Peter Beard (centre) and models outside Studio 54 in New York

I knew by that point that he’d had his 40th birthday party at Studio 54, had been pals with Mick Jagger and Truman Capote, was previously married to Cheryl Tiegs, and that everyone I knew in New York had a cherished Peter Beard story — very often including mountains of cocaine.

But it was his work that first turned me on to him, in the late 1990s, when I was in college. The images of him, hip-deep in a Nile crocodile somewhere in the wild north of Kenya, of a scantily clad Janice Dickinson being licked by a leopard, the dense, technicolor collages of his photographs, illuminated by his enchanting, sinuous handwriting, quoting Darwin or Karen Blixen, pictures scuffed by sands and festooned with foreign beer labels, ephemera from his travels, and splattered with blood and ink lit my brain on fire.

Not only did he look like a silent movie star in these images, but the world that he’d built and so beautifully articulated seemed to appeal directly to me, with all of the wanderlust and angst and machismo a college-aged jock can manage. What’s more, the work all seemed so desperately important — crusading, as he was, for the conservation of elephants, of natural resources, and a balance to life on Earth.

So, yes, something like prophet, playboy, and provocateur all rolled up into one, is probably what I thought.

At the time, I was working at Andy Warhol’s Interview and so knew well of Peter’s long history with the magazine, knew of the notorious shoot he did for the cover in the 1970s for which he ordered several buckets of blood, duly scandalising everyone involved.

Everyone save Interview’s columnist at the time, Fran Lebowitz, who later told me: ‘It's just not my kind of thing, that kind of very showy eccentricity. It wasn't that uncommon then — the writing in his blood and all that kind of stuff. It was the kind of stuff that girls did... kind of crazy upper-class girls trying to get back at their parents for not paying attention to them or whatever.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The crowd Peter ran with at the time, the 54 crowd which included Warhol, was always out and about, Lebowitz told me, always on the scene. ‘You must understand,’ she told me, ‘these were not philosophers we’re talking about, not intellectuals; this was the party crowd.’ Though she did later admit that Peter was, ‘the most handsome straight man I ever met.’

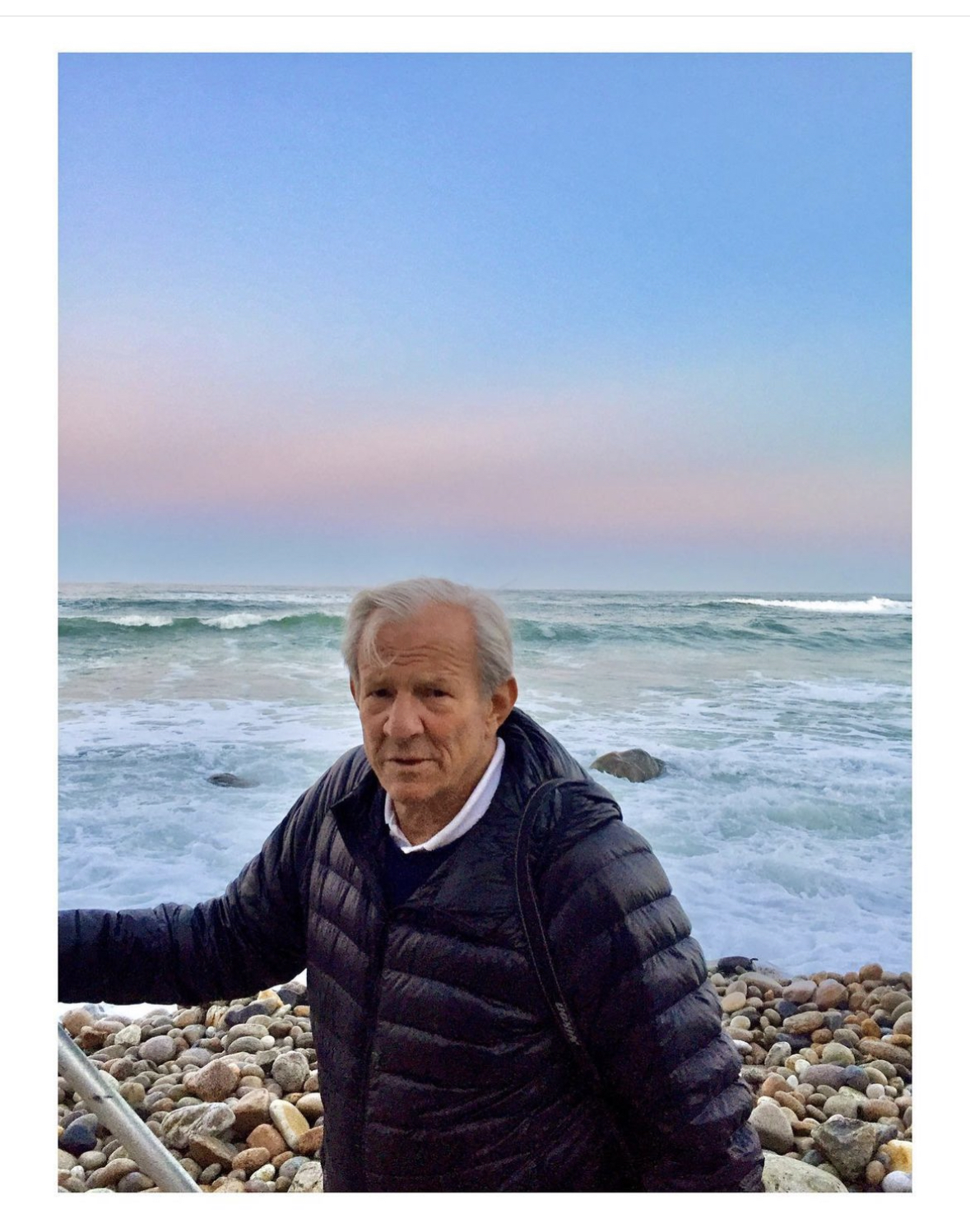

And still he was, even at 78 when I met him. Still an incorrigible seducer, charmer, cad. And he knew he had me the second I showed up to his house, the easternmost property on Long Island, way out on the tip of Montauk. Knew that he had a captive audience and, boy, he didn’t want to let go — kind of didn’t let go, as he put me up there for the weekend, in one of the clapboard cottages on the property, where I could freely frolic in my imagination with all the wonderful ghosts there.

With Halston, who’d holed up there for a summer in exchange for decorating the place, with The Stones who saw the infamous snake pit when it was still in action, before the windmill on the property burned down in 1977, taking with it all of the Warhols and Andrew Wyeths and Francis Bacons that Peter had.

Peter Beard at the 1979 RFK Tennis Tournament at Flushing Meadows, New York.

Not that he ever expressed any regret or nostalgia about it, or anything, ever in his life. In fact, he told me several times during our time together that he had made a choice in his life, right around the time of the fire, to never look back, never ever, to remain utterly present, in the now, for as long as he lived. Which I must have thought pure zen genius or something, and not the slightly sociopathic coldness as it occurred to me to be later on.

For hours and hours and hours in Montauk, we talked and ranted and raved, stopping only for a sushi break, wandering down the stairs he’d built on to the cliff leading to the sea, rambling over the rocks there, showing each other our journals, gawping at pictures of supermodels, watching the sunset, laughing, teasing, and philosophising.

For a long time, Peter and I looked through his diaries — leafing through the fatly layered collages he’d made religiously, almost daily, throughout his life in his large format Lett’s daily planners. And while I marvelled, he just sort of scoffed, telling me that they were just made in pursuit of escapism, that they were nothing more than doodles, piling ups of the detritus of his life, the scraps he found around him, notes to return some phone call, scores from the Giants game, receipts, tabloid cuttings, porn, poetry.

In a letter to the Getty Foundation, Peter’s pal Francis Bacon described these diaries as one of the most important works of their era. And I tend to agree.

Apart from the spellbinding beauty of them, I think that they are the best depiction we have of consciousness in the 20th century — with all of its distractions and obsessions, the kind of mournful boredom mixed with the noise of advertising, of pop culture, the images of violence and celebrity and the macabre. I already thought all this at the time and tried to get Peter to comment on them, but he just sort of shrugged. Meh, it’s what I did, he seemed to be saying, no biggie.

Peter had suffered a series of strokes a few years earlier and at times during my visit his speech was impaired, as if something was impeding his syntax, causing him to sort of freeze mid sentence. In the silences, I leaped out with ideas, suggestions, help, concern, to which he just smiled and shook his head and we would fall into a comfortable silence together.

Then, suddenly, catching his momentum, he would unravel huge spools of ideas, opinions, stories, observations. At these points he seemed incredibly childlike, Puck-ish. Like a loosened helium balloon. And, when his wife wasn’t there and shooshing him, and even when she was, he’d say some absolutely unpublishable things, unforgiveable things, which at the time I couldn’t make sense of.

Later, when I began writing my book about Peter, the family explained that he’d had dementia. And I wonder if I thought that explained it.

Of course, I spent a lot of time, in the researching and writing of the book, trying to come to grips with some of Peter’s reprehensible behavior throughout the course of his life. Tried to see the man in full, a man I only knew for the last few years of his life, tried to see, through him and his behavior, his appetites and his artwork, what I could of his life and times.

And I know what Edmund White would say, that, ‘biography is usually the revenge of the little people on the big people (the application of the biographer’s petit bourgeois campus morality, for instance, to the uncautious [sic] international high flyers).’ Which very well may be.

Peter was, more than anyone else I can think of, the most uncautious high flyer. So it is very nice to think back, for the first time in a long time, about the meeting that first kicked off our friendship. And, which ultimately changed my life. What did I know?

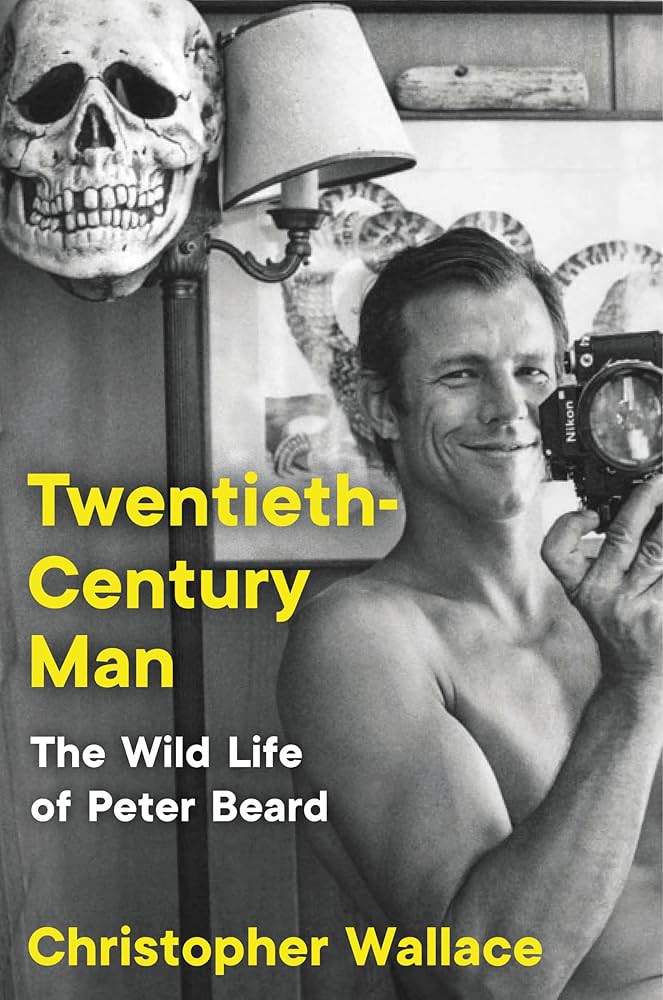

Christopher Wallace is the author of ‘Twentieth-Century Man: The Wild Life of Peter Beard’ which is out in paperback, now.

Christopher Wallace is a writer and photographer. His biography of the late photographer Peter Beard, ‘Twentieth-Century Man: The Wild Life of Peter Beard’, was published by Ecco press. Before going freelance, Wallace was the US Editor of Mr Porter and the Executive Editor of Interview Magazine. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, The Paris Review, and on Substack, among others. Chris was born and raised in Los Angeles and once upon a time made a few short films that won some awards at festivals. Longer ago than that, even, he played college football, before eventually quitting the team to write poetry. He still makes similarly poor career decisions — his words, not ours.