1775: The year Britain produced a dazzling generation who changed the world

From Jane Austen to J. M. W Turner, 1775 was a stellar year for Britain's creative industries.

'They are joining Field to Field & House to House in so unbounded & precipitate a Manner that Hampstead will be ere long reckoned the suburbs of this City,’ noted an Irish clergyman of his visit to London in the summer of 1772.

In the capital, developers were at work. The Dowager Duchess of Bedford approved plans for Bedford Square in 1774; shortly afterwards, work began on Manchester Square. New turnpike roads encouraged Britons to travel: Dr Johnson’s biographer James Boswell recorded that the journey from Edinburgh to London could now be accomplished in merely five days. London’s shops were the wonder of visiting foreigners. By the final quarter of the 18th century, political stability, a financial revolution facilitated by the establishment of the Bank of England in 1694, expanding trade both at home and abroad — including as a result of gains made in the War of the Spanish Succession and the Seven Years’ War — and burgeoning technological innovation, from ceramics manufacture to steam engines, appeared to guarantee the prosperity of a nation of property owners and shopkeepers.

Britain 250 years ago was boisterous, thriving and confident, its national character, in the words of one historian, ‘vital, tough, vigorous and enterprising’. Uxorious, dutiful and stolid, George III commanded widespread affection.

Overseas, British power continued to grow. Five years after his discovery of Australia, in July 1775, Capt James Cook returned from a government-sponsored circumnavigation of the southern hemisphere. Pride in Cook’s achievement would go some way to balancing anxiety at rebellion in Britain’s 13 colonies across the pond that, eight years later, led to American independence.

For many, however, in 1775, the horizon appeared clear. The annual rent of ‘a great house’ in Grosvenor Square rose to £500, aristocratic households employed a staff that could number more than 40 and, at the fashionable new Royal Academy (RA), portraitist Sir Joshua Reynolds presided more or less benignly. This was the year in which a handful of pre-eminent cultural luminaries were born, too. Each bequeathed a legacy that continues to shape our identity, outlook, understanding and joy.

Jane Austen

‘There is an innate levity in woman, that nothing can overcome,’ offers a character in Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s comedy of manners The Rivals, first performed at Covent Garden Theatre in January 1775.

Not so Jane Austen (1775–1817), who was born on December 17 in the Hampshire village of Steventon, one of eight children of an affectionate, articulate clergy family of modest means.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Lord David Cecil suggested of Austen that she ‘was born in the eighteenth century and spiritually speaking she stayed there’: her teenage reading of Henry Fielding, Samuel Richardson, Oliver Goldsmith, Laurence Sterne, Joseph Addison, Samuel Johnson and Fanny Burney left a lifelong imprint.

Sharing from an early age the ‘power of eloquent composition’ that her mother discerned in her eldest brother, James, Jane embarked on her first stories and poems after her 10th birthday, despite her later view that she could ‘boast [herself]... the most unlearned and uninformed being that ever dared to be an authoress’.

That she did dare has enriched the lives of millions of readers — and, more recently, film and television viewers — for more than two centuries. Sales of her best-loved novel, Pride and Prejudice, exceed 20 million copies.

Thomas Girtin

'Thomas Girtin’s luminous topographical watercolours — the finest of any artist of his generation bar Turner, with whom he shared his first patron — have exhilarated viewers for 200 years: dramatic, atmospheric, romantic and, at their best, technically dazzling.

Born on February 18, Girtin (1775–1802) was 15 when, for the first time, a print based on one of his drawings was published; four years later, he exhibited his first painting at the RA. In a short career, the London-born brushmaker’s son travelled extensively. In 1797, the RA exhibited 10 pictures of views of Yorkshire and northern England; the same year, he visited the West Country.

Of Welsh scenes painted the following year, Lloyds Evening Post noted ‘all the bold features of genius... Mr Girtin, we predict, will stand very high indeed in professional reputation’, an assessment that proved true then and since.

Girtin died at the young age of 27. ‘Had Tom Girtin lived, I should have starved,’ commented Turner, who particularly admired The White House at Chelsea of 1800 (above).

Richard Westmacott

Born on July 15, Richard Westmacott (1775–1856) achieved the unique distinction among British neo-Classical sculptors of being rated as highly as Antonio Canova: in 1822, the Duke of Bedford paid more than £1,000 for Westmacott’s Psyche, a price previously only commanded by the Italian master. The same year, Westmacott’s Wellington Monument, depicting the Iron Duke as an 18ft-high Achilles modelled from melted-down Napoleonic cannon, prompted both ribaldry and outrage — despite its fig leaf, this was London’s first new piece of naked sculpture.

His was a markedly successful career. The son of a sculptor who specialised in chimney-pieces and church monuments, Westmacott became the leading official sculptor of his time, one of the committee that advocated purchase of the Parthenon Marbles in 1816 and knighted by Queen Victoria in 1837. His final major work was a pediment sculpture for the British Museum, The Progress of Civilisation.

Agnes Bulmer

‘Air built and baseless all, are earth’s delights... They bud and wither in a winter’s day,’ wrote 17-year-old Agnes Bulmer (1775–1836). Like the better-known Jane Austen, Bulmer — born Agnes Collinson on August 31 — began writing as a child: her first poem, On the Death of Charles Wesley, was published when she was 14. Her efforts earned her a letter of thanks from Charles’s brother John Wesley, the founder of Methodism and a friend of her parents, who had baptised baby Agnes.

Throughout Bulmer’s life, her strong religious faith provided material for her writing, as did the experience of death, including that of her husband, Joseph, in her thirties and her mother’s death in 1825. That year, Bulmer embarked on what, over nine years, became her 12-volume, 14,000-line magnum opus, Messiah’s Kingdom. She wrote, according to a Victorian biographer, ‘with a... depth of conviction [and] impassioned eloquence’, but her fame chiefly rested on her bestselling 1836 biography of leading female Methodist Elizabeth Mortimer. Truth, she noted in her introduction, ‘emits a splendour’. Hear, hear.

William Crotch

‘The musical phenomenon of Norwich’, William Crotch (1775–1847), born on July 5, was two when he first learnt to play God Save the King on a small house organ; he performed for George III the following year. Eagerly, his parents capitalised on his prodigious talents. Aged seven, William performed a series of harpsichord and violin concerts: the Oxford Journal described him as ‘Master Crotch, the MUSICAL CHILD’.

Months later, he was advertised as having added the organ to his repertoire and, at the tender age of 15, he was appointed organist at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford.

His was a meteoric, if not always happy career — he would later claim to have found being exhibited as a child prodigy a humiliating business — and, in 1822, he was appointed first principal of the Royal Academy of Music.

Crotch composed oratorios, concertos and anthems for the organ and, although he is an overlooked figure today, Lo! Star-led chiefs and Be peace on earth, from his oratorio Palestine of 1812, remain prominent among cathedral organists’ repertoires.

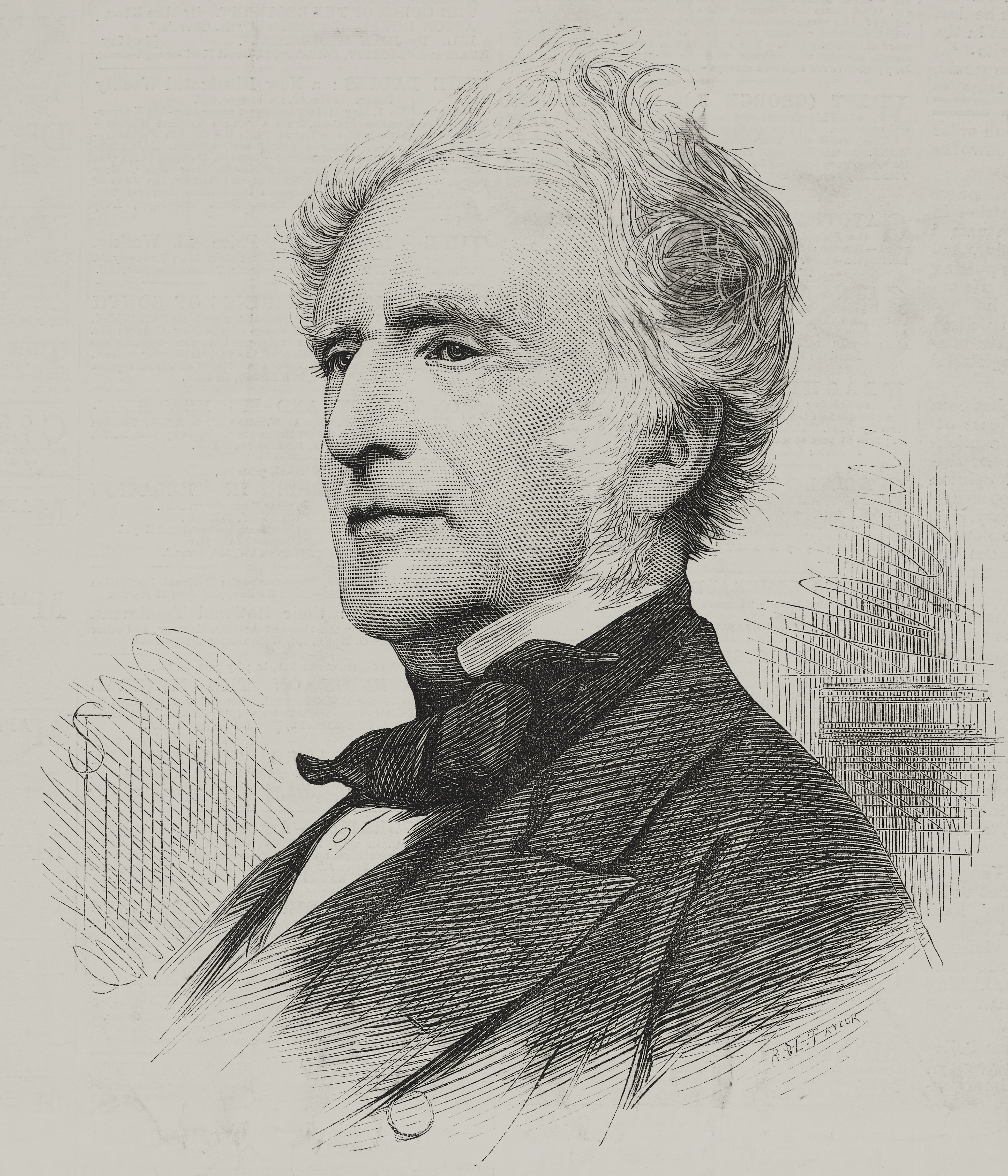

J. M. W. Turner

‘The painter of light’, of ‘the poetry of silence’, in Ruskin’s view, as well as of ‘turbulence and wrath’, Turner (1775–1851), who was born on April 23, transformed English painting. For his pains, he inspired admiration, consternation and considerable disdain among his contemporaries. In an exhibition of Turner’s paintings in 1840, a reviewer in The Morning Chronicle discerned ‘flaming abortions’ and ‘freaks of chronomania’; he likened a painting of Bacchus and Ariadne (Tate) to an omelette.

One of Turner’s great achievements was to redefine realism, in a manner uniquely his, in favour of impact, impression and atmospheric effect — what Crabb Robinson called ‘an atmosphere and play of colours all his own’ and the president of the RA condemned as ‘crude blotches’; his later work is numinous, by turns brooding or sparkling. On his death in 1851, Turner was buried in St Paul’s Cathedral in London, a fitting resting place for an artist who had conferred international pre-eminence on British painting and, in works such as Norham Castle of 1840 and the well-known Rain, Storm and Speed (above), transformed this nation into a realm of poetry, wonder and majesty.

Charles Lamb

‘A talk with the reader’ is how Charles Lamb (1775–1834) described the essays he published under the pen name ‘Elia’ in The London Magazine, from 1820, and their conversational, sometimes colloquial, idiosyncratic and personal style contributed significantly to the essays’ success — particularly once they were published in two collections in 1823 and 1833.

Lamb, born on February 10, left school at 14, with a severe stutter; at 17, he became a clerk in the East India Company, where he remained (with little fondness for the work) for 33 years.

His life was scarred by tragedy — his sister Mary’s murder of their mother, in a fit of insanity, cast Charles as Mary’s lifelong keeper — but his best-known writing, a staple of British reading until the Second World War, is notable for its lack of cynicism or bitterness. ‘No one ever stammered out such fine, piquant, deep, eloquent things in half a dozen half-sentences,’ wrote William Hazlitt of Lamb as a conversationalist. Hazlitt’s verdict rings equally true of Lamb’s magnetic essays.