Why does BBC Radio 4 broadcast 'the pips' at the top of the hour?

The Greenwich Time Signal has been an ubiquitous part of BBC Radio for a century, but few know what it really is and where it came from

In September 17, 2008, anyone listening to the BBC’s local and national radio stations could have been forgiven for thinking they had woken up in an alternate reality. Why? The most reliable noise in the world had just gone somewhat awry.

The Greenwich Time Signal ‘pips’—those half-dozen high-pitched, strangely reassuring bursts of time-keeping precision noise—went horribly wrong that morning. Firstly, they were six seconds late; secondly, there was one pip too many.

This was a rare glitch in a system that for 100 years has been informing radio listeners across the globe exactly how to set their watches, when they should be leaving the house to catch a train or simply whether they should contemplate going to bed. It’s a precious device and not one that the BBC is prone to using in other contexts lest confusion should be caused.

‘Radio 4 is very fond of the pips and we hope the audience is, too. If pips are heard out of context, it can be quite disconcerting,’ says Katy Hubbard, head of presentation for Radio 4. ‘For that reason, we ask our programme makers to alert us in advance if they wish to use the pips. We will allow three out of context, but not the long final pip.’

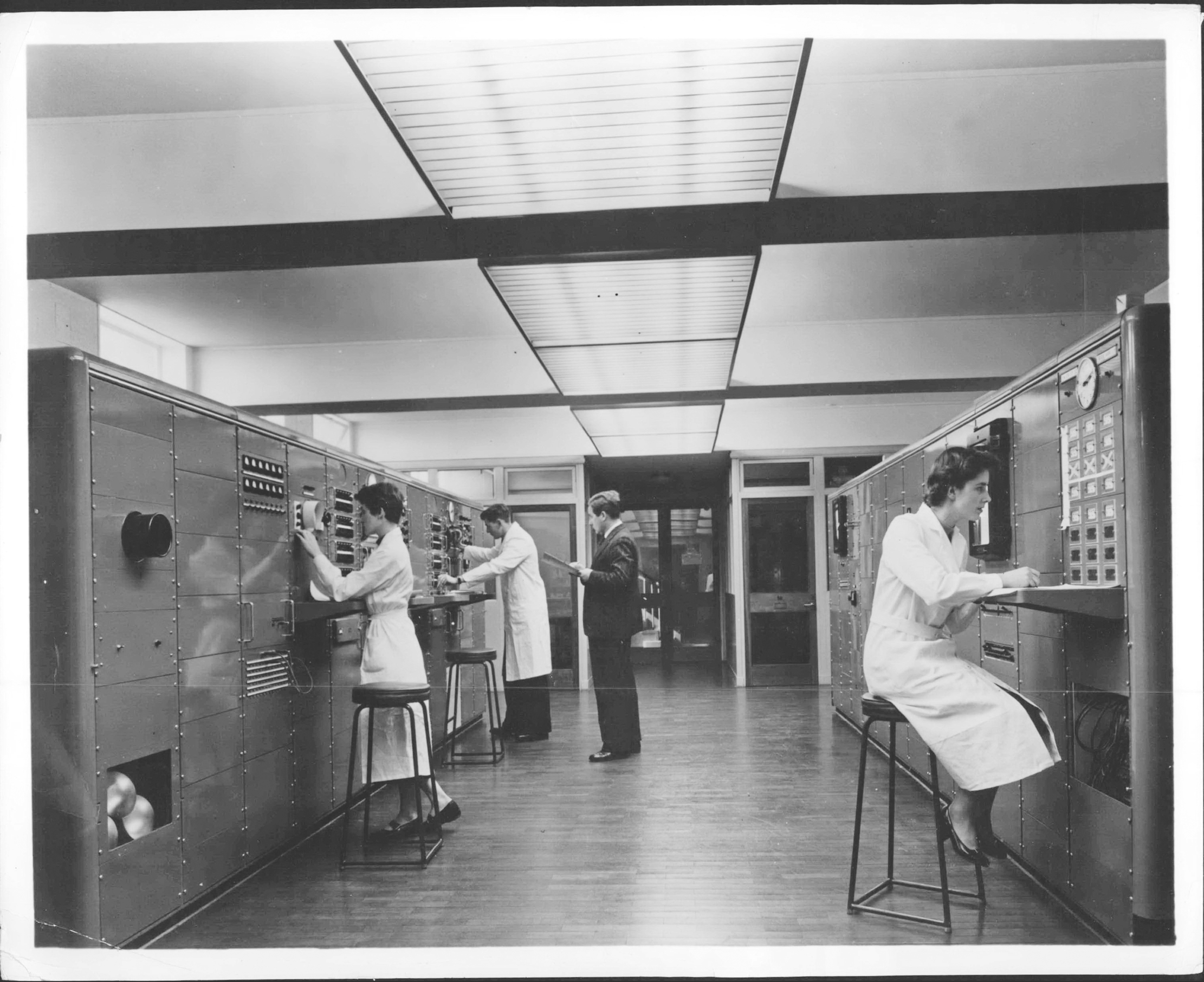

When used correctly, the Greenwich Time Signal (GTS) is six short tones, broadcast at one-second intervals. The sixth, longer pip indicates the beginning of the hour; the actual moment when the hour changes is at the very beginning of the last pip. The brainchild of ninth Astronomer Royal Sir Frank Dyson and Sir John Reith, then managing director of the BBC, they were first broadcast by the BBC on Tuesday, February 5, 1924, at exactly 9.30pm. The pacing of the pips was taken from the movement of a long-case pendulum clock. The movement generated electrical impulses that were sent to the primitive BBC studios on Savoy Hill for wireless transmissions.

It was a huge improvement on Greenwich Observatory’s original time-keeping methods, which entailed dropping a ball from a mast on the building’s rooftop, on the hour, so that passing ships on the River Thames (and anyone who happened to be looking the right way) were alerted to check their chronometers (the bright-red Time Ball still rises and drops, at 12.58pm and 1pm respectively, to this day).

All worked weirdly well, barring a skirmish in 1937 when the Royal Navy—which ran the Observatory—issued the BBC with a bill for using their services. The bill was never paid, the BBC retorting that it had never charged the Royal Navy for services of the Shipping Forecast. Quid pro quo.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Even after the pips were introduced, the quest for total accuracy continued and, in 1972, the final tone was lengthened from one-tenth of a second to a half-second, to allow for irregularities in the rotation of the earth. Today, GTS is timed relative to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) from an atomic clock in the basement of Broadcasting House.

The alternative, and precursor, to UTC is Solar Time (UT1)—time calculated using the position of the sun in the sky. We use leap seconds, introduced in the same year, to accommodate for differences between the two time-keeping methods. When they occur, keen-eared BBC listeners will hear seven pips, not six.

‘They cut through the noise of the day,’ says Ms Hubbard. ‘My broadcast colleagues might not necessarily see them as a calming presence, as, often, it means they race to finish their programme. No one likes to crash the pips. But I think they’re an essential part of the soundscape of radio.’

The Country Life Podcast

Listen to all the episodes of the Country Life Podcast.

Curious Questions: Who invented tennis?

It's 150 years since the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club was formed – though originally it was solely for

Curious Questions: Do love potions actually work?

The idea of a potion that can make someone fall in love is as old as the idea of love

Curious Questions: Why do clocks go clockwise?

There's nothing to stop the hands of a clock from running backwards — indeed, some actually do — but the overwhelming majority

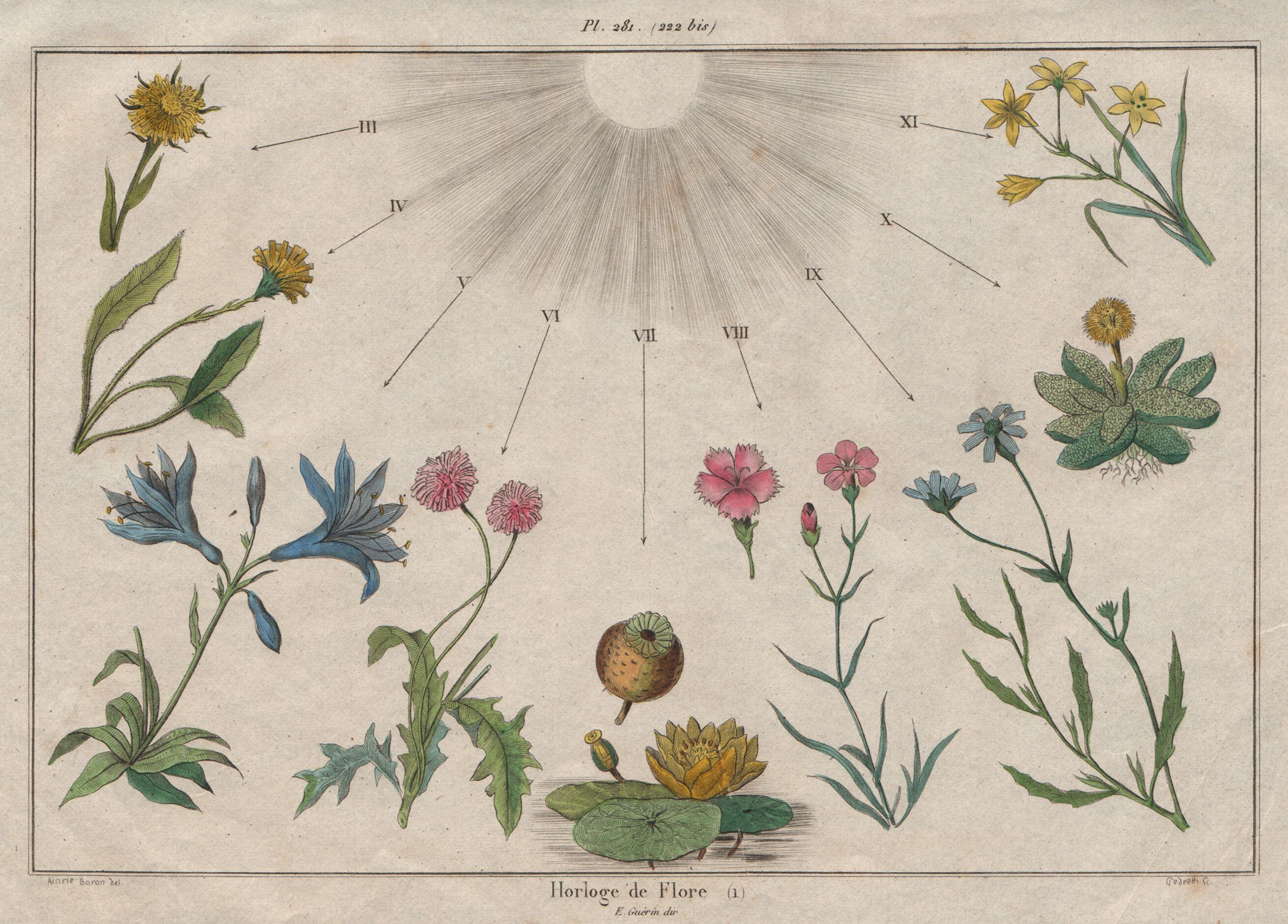

Curious Questions: What is Linnaeus’s Flower Clock?

Martin Fone takes a look at one of the most ingenious uses of plants ever imagined by mankind: Linnaeus’s Flower

Credit: Strutt and Parker

Best country houses for sale this week

An irresistible West Country cottage and a magnificent Cumbrian country house make our pick of the finest country houses for

Rob is a writer, broadcaster and playwright who lives in Brixton, South London. He regularly contributes to publications including the Daily Mail, Daily Telegraph and Conde Nast Traveller. Rob is the Special Correspondent for the BBC Radio Four programme Feedback and can also be heard on the From Our Own Correspondent programme on BBC Radio Four and the World Service. His first play, 'The Gaffer', premiered at the Underbelly Theatre as part of the Edinburgh Fringe in 2023.

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher

-

Curious Questions: Why do golf balls have dimples? And why are tennis balls furry?

Curious Questions: Why do golf balls have dimples? And why are tennis balls furry?As the weather picks up, millions of us start thinking about dusting off our golf clubs and tennis rackets. And as he did so, Martin Fone got thinking: why aren't the balls we use for tennis and golf perfectly smooth?

By Martin Fone

-

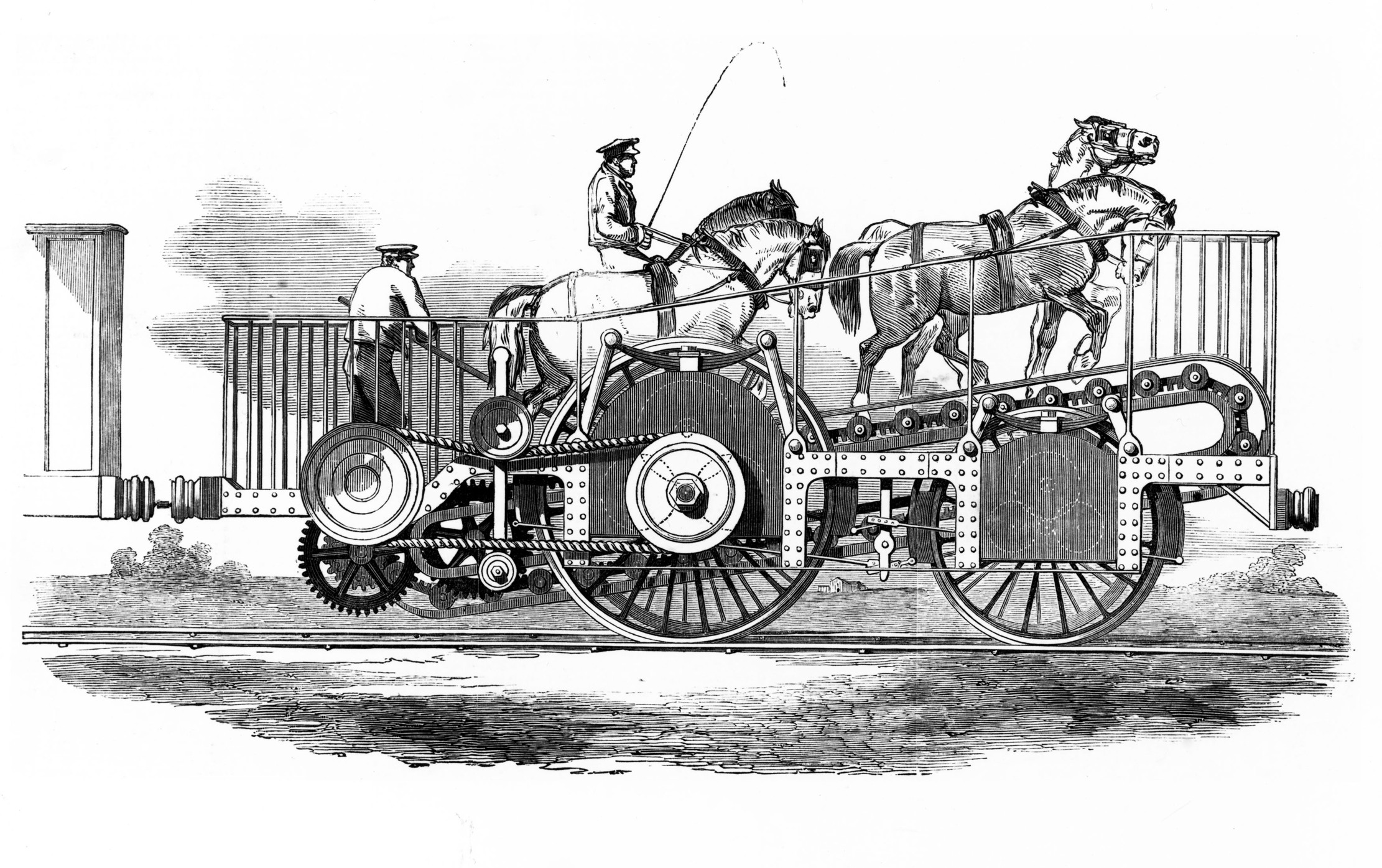

Curious questions: How a horse on a treadmill almost defeated a steam locomotive

Curious questions: How a horse on a treadmill almost defeated a steam locomotiveThe wonderful tale of Thomas Brandreth's Cycloped and the first steam-powered railway.

By Martin Fone

-

You've got peemail: Why dogs sniff each other's urine

You've got peemail: Why dogs sniff each other's urineEver wondered why your dog is so fond of sniffing another’s pee? 'The urine is the carrier service, the equivalent of Outlook or Gmail,' explains Laura Parker.

By Laura Parker

-

Curious Questions: Which person has spent the most time on TV?

Curious Questions: Which person has spent the most time on TV?Is it Elvis? Is it Queen Elizabeth II? Is it Gary Lineker? No, it's an eight-year-old girl called Carole and a terrifying clown. Here is the history of the BBC's Test Card F.

By Rob Crossan

-

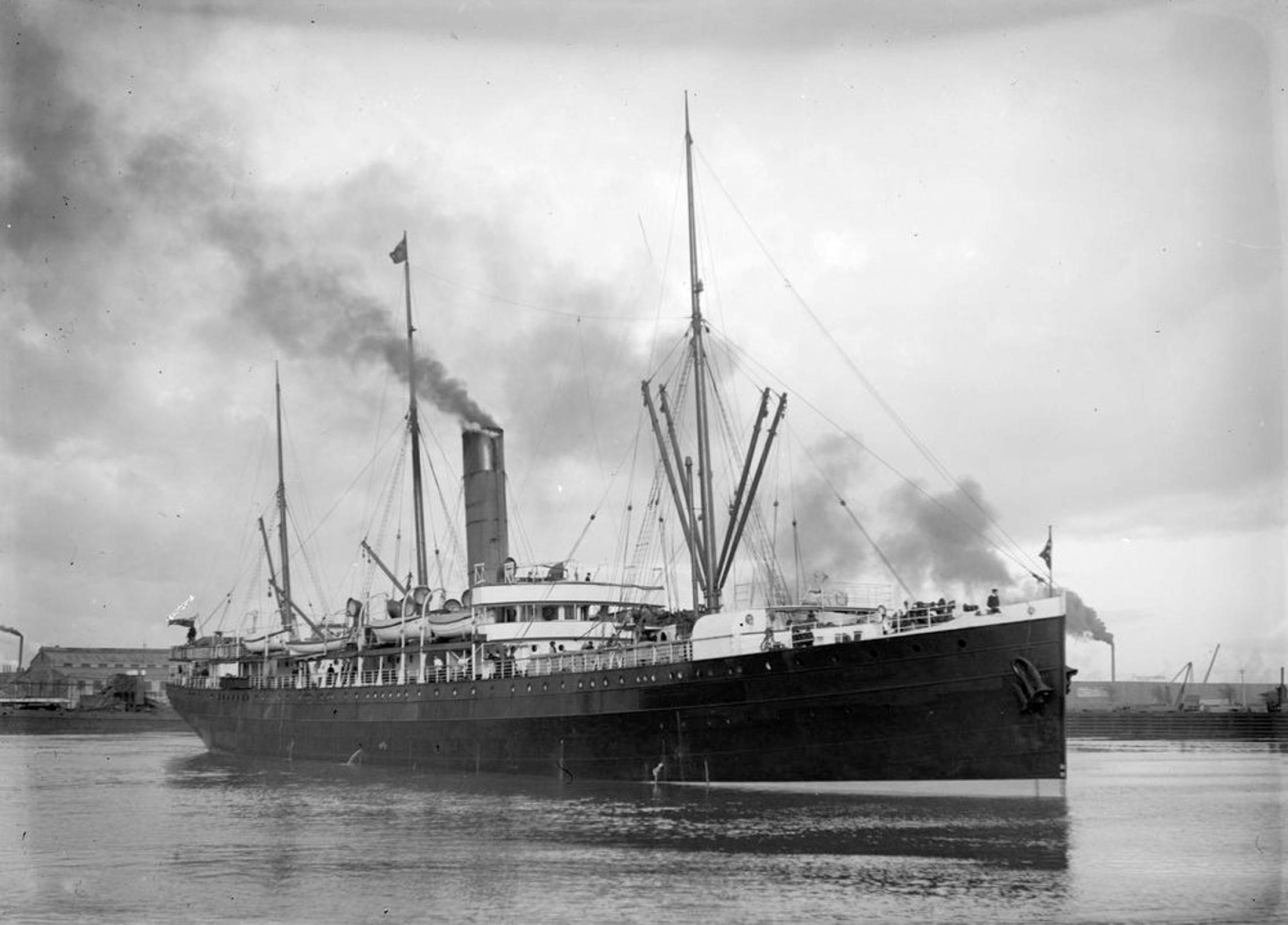

The ship that was in two different centuries, two different years, two different months, two different days and two different seasons, all at the same time

The ship that was in two different centuries, two different years, two different months, two different days and two different seasons, all at the same timeOn December 31, 1899, the SS Warrimoo may have travelled through time — but did it really happen?

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Was music's famous 'Lady of the Nightingales' nothing more than a hoaxer?

Curious Questions: Was music's famous 'Lady of the Nightingales' nothing more than a hoaxer?Beatrice Harrison, aka ‘The Lady of the Nightingales’, charmed King and country with her garden duets alongside the nightingales singing in a Surrey garden. One hundred years later, Julian Lloyd Webber examines whether her performances were fact or fiction.

By Julian Lloyd Webber

-

Curious Questions: Who wrote the Happy Birthday song?

Curious Questions: Who wrote the Happy Birthday song?There are few things less pleasurable than a tuneless public rendition of Happy Birthday To You, says Rob Crossan, a century after the little ditty came into being

By Rob Crossan

-

Why do we get so many April showers?

Why do we get so many April showers?It's the time of year when a torrential downpour can come and go in minutes — or drench one side of the street while leaving the other side dry. It's all to the good for growing, says Lia Leendertz as she takes a look at the weather of April.

By Lia Leendertz