With love from Father Christmas: J.R.R. Tolkien's enchanting Christmas letters to his children

For nearly a quarter of a century, J. R. R. Tolkien sent his children elaborate letters and pictures from the North Pole. Ben Lerwill explores the penmanship, kindness and magic that went into Letters From Father Christmas.

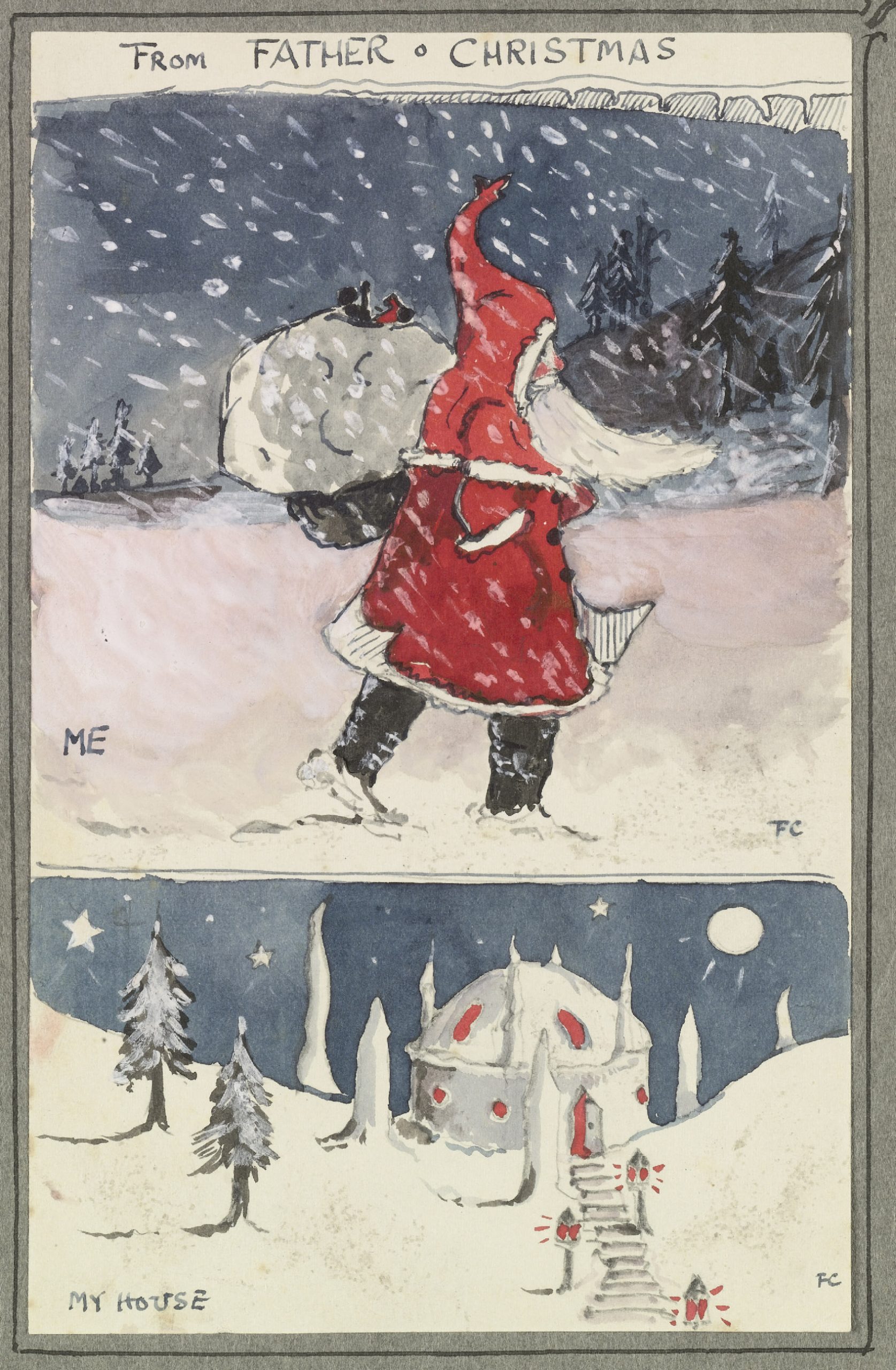

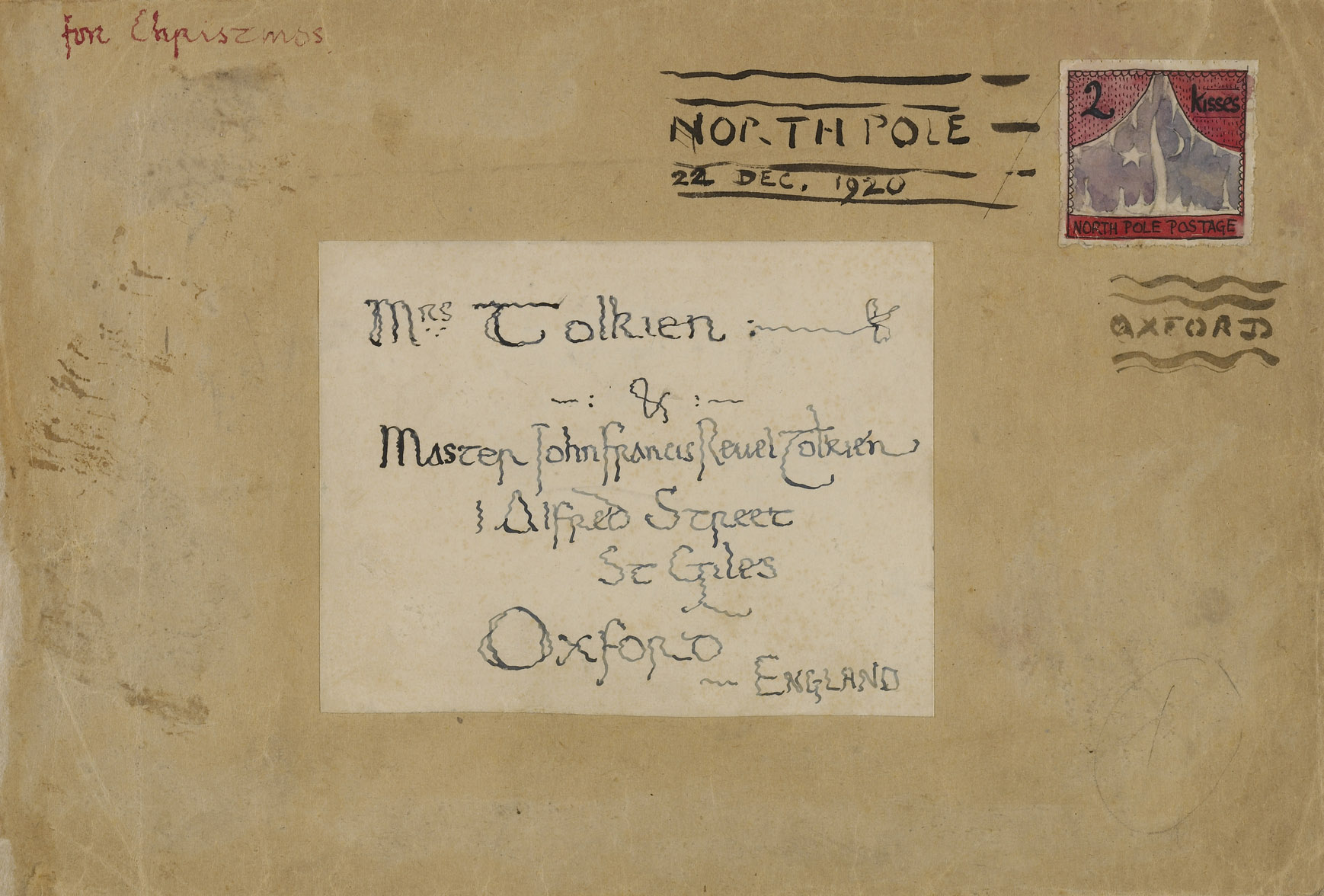

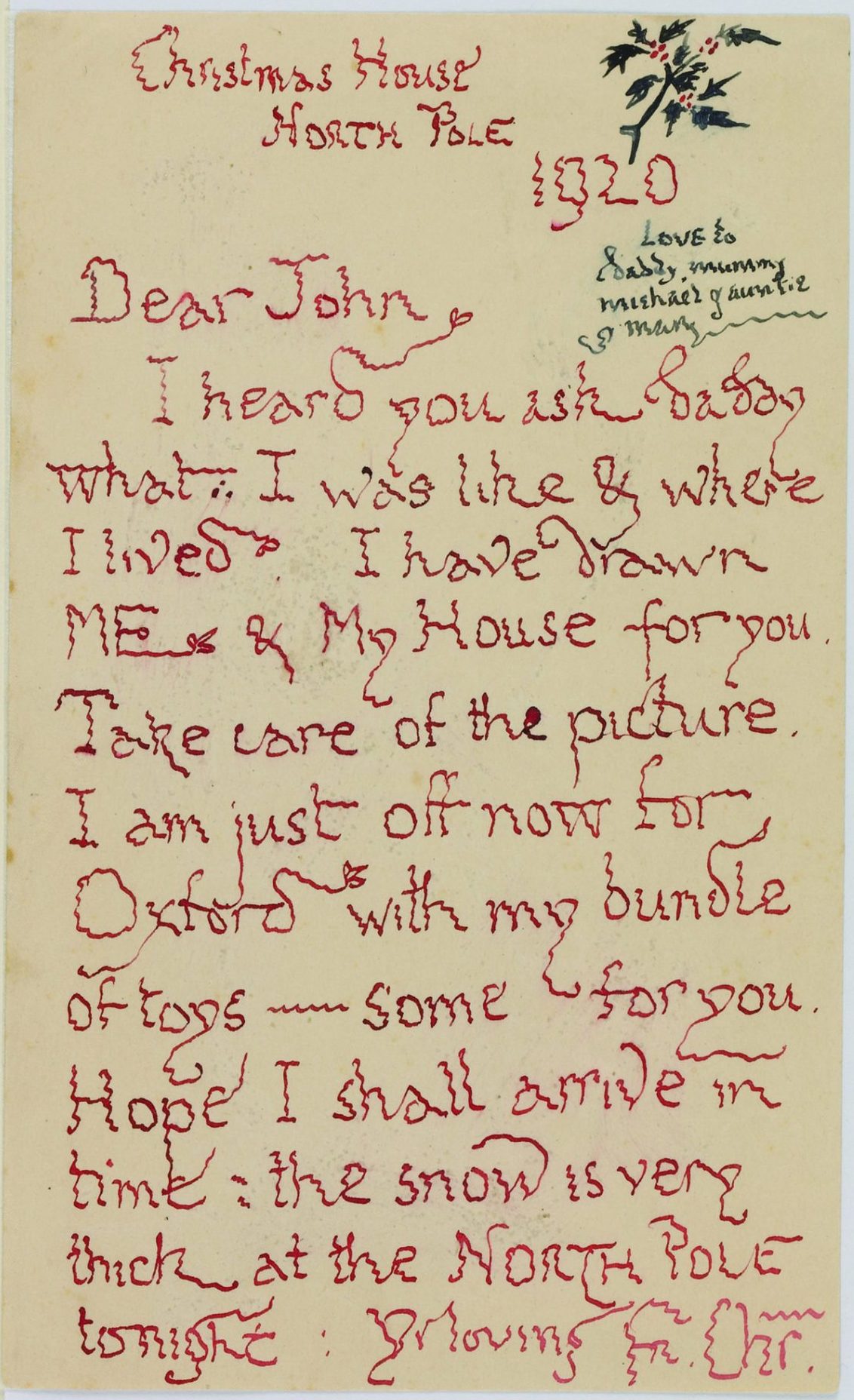

One hundred years ago, in late December 1920, a letter landed on the doormat of an Oxford home. It was addressed to a three-year-old boy named John and the envelope bore an exotic stamp priced at ‘2 kisses’. Inside was a hand-painted card showing a familiar, red-coated whitebeard treading patiently through the snow. Underneath, painted by the same hand, was a yurt-like, snow-covered dwelling tucked behind pine trees. The two intricate little artworks were captioned ‘Me’ and ‘My House’.

The strange, shivery handwriting inside the card informed young John that the sender was ‘just off now for Oxford with my bundle of toys — some for you. Hope I shall arrive in time: the snow is very thick at the North Pole tonight’. With this brief, but beautifully rendered picture card, a tradition was born that would last almost a quarter-century, at the same time shining a spotlight on the creativity and affections of one of our most celebrated writers.

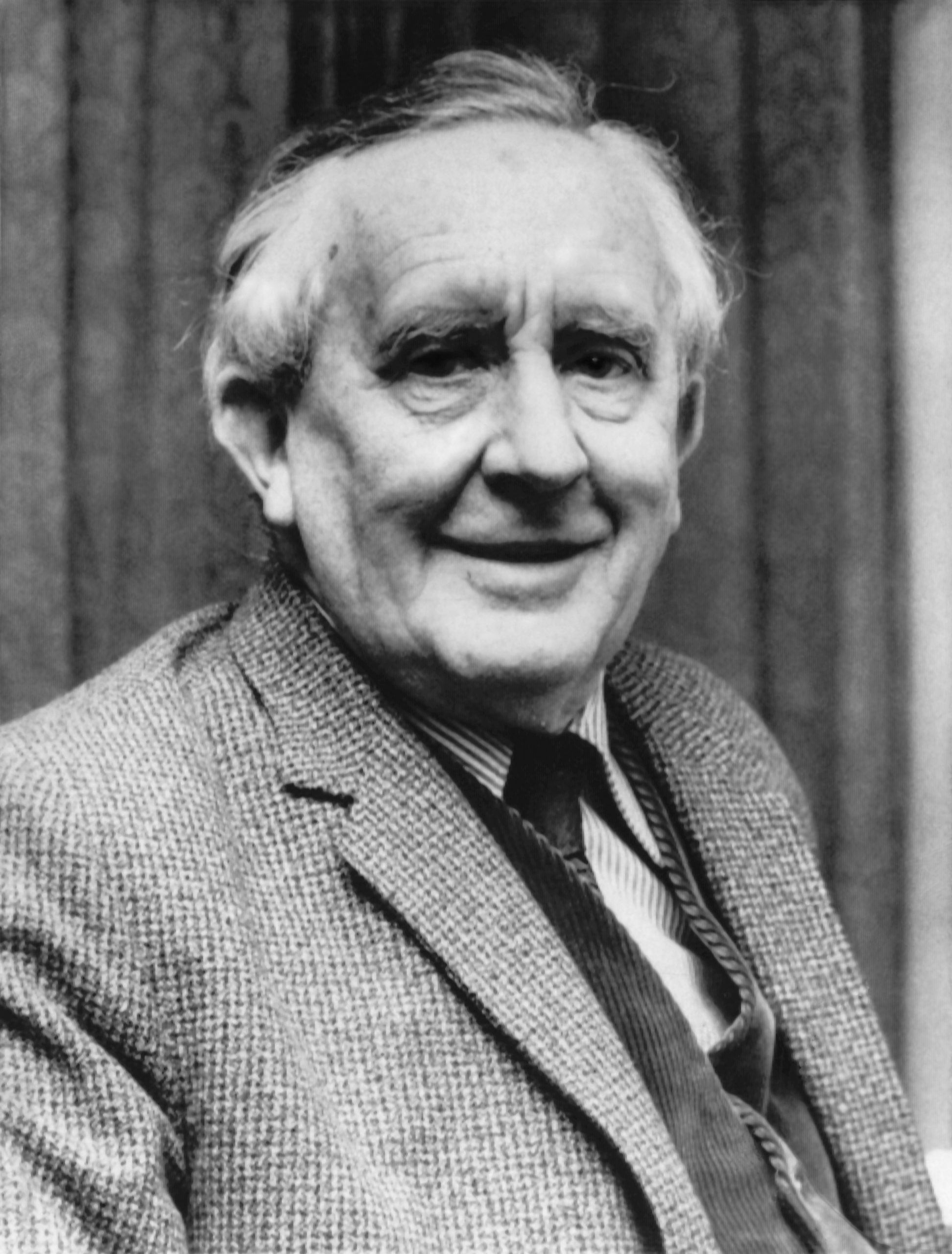

J. R. R. Tolkien needs little introduction, even for those who don’t know their Balrogs from their Bagginses. The pipe-puffing creator of high-fantasy novels and ardent lover of the British countryside was in his late twenties when he penned the card above. He went on to repeat the correspondence, using ever more inventive designs, language and ideas, every Christmas for the next 23 years.

As with so many things in his life, he gave the task dedication. By the time he sent his final letter from Father Christmas, a poignant wartime dispatch in 1943, his four children (John being the eldest, followed by Michael, Christopher and Priscilla) were all well into their teens and twenties.

The letters were far more than cursory festive greetings. As time went by, Tolkien fleshed out his North Pole world with recurring characters, notably a note-scrawling polar bear with a spelling problem and a multi-lingual elf named Ilbereth with a knack for clerical work. Fire-starting goblins, snowball-throwing red elves and partying cave cubs also appeared, turning each year’s letter into a fresh instalment of a richly entertaining — and often hilarious — winter saga. Some ran to more than 1,000 words.

In 1976, three years after the writer’s death, these lovingly crafted letters and artworks were gathered together and published by the Tolkien estate. The resulting book, Letters From Father Christmas, enjoyed little of the fanfare of his best-known works, but warm praise still came its way. The Times described it as ‘Tolkien at his relaxed and ingenious best’ and The New York Times decreed: ‘Father Christmas lives. And never more merrily than in these pages.’ Almost 45 years on, the book stands not only as a little-heralded festive classic, but as a touching snapshot of another time.

Much of what makes the letters so special is the thought behind them. When that first envelope appeared on the doormat in 1920, Tolkien was not yet an Oxford professor, much less a well-established author. He had been recently demobbed from the army, after contracting trench fever as a young lieutenant at the Somme. The Hobbit — also initially written for the entertainment of his children — was still some 17 years from publication and The Lord of the Rings was more than three decades away.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The letters, for all their elaborate calligraphy, dense narratives and colourful penmanship, represent something simple: the time, kindness and attention of a parent. When, in 1926, Tolkien’s Father Christmas explains that a giant firework ‘turned the North Pole black, shook the stars out of place, broke the moon into four — and the Man in it fell into my back garden. He ate quite a lot of my Christmas chocolates’, the writer’s playful relish is tangible.

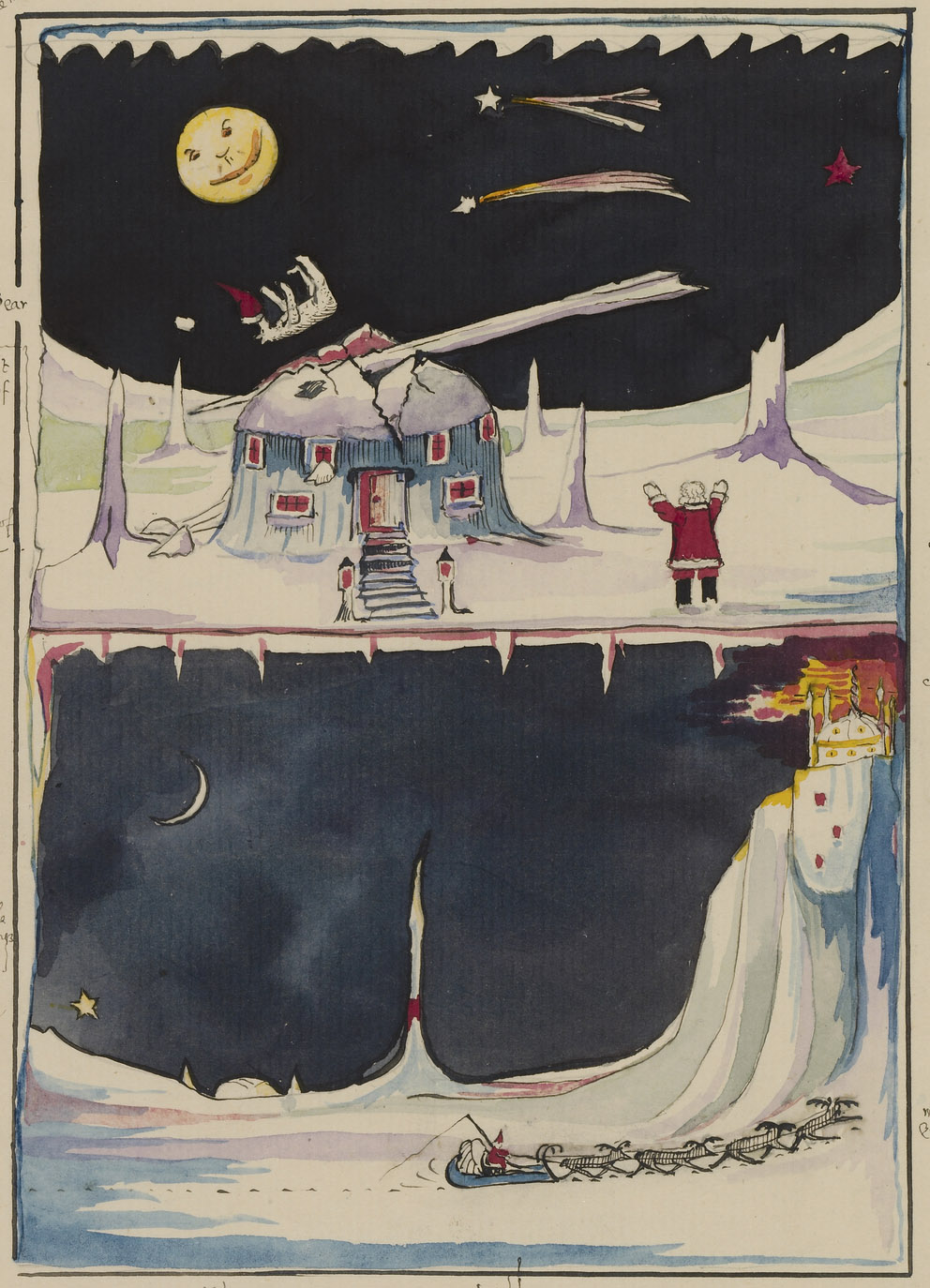

Likewise, when Polar Bear interrupts the 1931 missive to admit to sampling food parcels (‘Somebody haz to — and I found stones in some of the kurrants’), it’s easy to picture the family flocking to the letter, their Christmas excitement being cranked higher. And when, in 1932, the correspondence is accompanied by a gorgeous multi-part painting showing reindeer swooping over the Oxford skyline and Father Christmas creeping through a grotto with a flaming torch, we get a sense of the hours that have gone into its creation. The book, incidentally, reproduces all letters, envelopes and artworks.

There’s something deeper on show than good humour and fatherly indulgence, too. The architect of the labyrinthine world of Middle Earth frequently included fantastical events and otherworldly flourishes in his letters that could be straight from the pages of his novels. There are examples of the filmic, sweeping mountain illustrations that would appear on the original cover of The Hobbit. We hear about a 400-year-old great horn (‘its sound carries as far as the North Wind blows’), as well as the goblin war of 1453. Tolkien goes to the trouble of creating an entire goblin alphabet of hieroglyphs and even a letter for his children to translate.

Tolkien’s stories have always been wonderful hybrids of the known and the unknown. The Warwickshire countryside, the Malvern Hills and Lancashire’s Ribble Valley have all inspired various settings in his works. Yet he imbues them with an extra magic — and the same is true of his Father Christmas letters.

The final letter, in war-torn 1943, hints at the intrusion of modern life more than any other. At the same time, it displays an optimism that can still be valued, in 2020 as much as ever. ‘My dear Priscilla, A very happy Christmas!… After this I shall have to say “goodbye”, more or less: I mean, I shall not forget you… My messengers tell me that people call it “grim” this year… and so it is, I fear, in very many places I was specially fond of going; but I am very glad to hear that you are still not really miserable. Don’t be! I am still very much alive, and shall come back again soon, as merry as ever.’

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to last

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to lastKitchen and joinery specialist Artichoke had several clever tricks to deal with the fact that natural wood expands and contracts.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025Friday's quiz is an Easter special.

By James Fisher

-

How to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen

How to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen2025 marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen's birth. Here are exhibitions, events and more — happening across the UK — that mark the occasion.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Unputdownable: 12 page turners to see you through the rest of the winter

Unputdownable: 12 page turners to see you through the rest of the winterFrom cookbooks to cricket, biographies to Sunday Times bestsellers, Country Life contributors name some of their favourite books from last year.

By Country Life

-

J.R.R. Tolkien: The life and times of the lord of the books

J.R.R. Tolkien: The life and times of the lord of the booksFrom a sentence born of an exhausting teaching job, J. R. R. Tolkien crafted a series of fantastical novels that, 50 years on from his death, still loom as large in our imagination as Sauron’s all-seeing eye, says Matthew Dennison.

By Matthew Dennison

-

How to build the perfect snowman

How to build the perfect snowmanIf we get lucky and the weather delivers a big fall of snow, Katy Birchall has the best recipe for building a splendid snowman that will be the envy of your village.

By Katy Birchall

-

Who wrote the Christmas Carols we know and love? 11 songs and their stories, from Silent Night to Good King Wenceslas

Who wrote the Christmas Carols we know and love? 11 songs and their stories, from Silent Night to Good King WenceslasMany of our best-loved and most moving Christmas carols started life as poems in search of a tune. Andrew Green uncovers the writers whose works were nearly forgotten, yet are now imprinted on the memory.

By Country Life

-

Thomas Hardy's Wessex vs the real-life Dorset: Which bits are real, which dreams, and which are exact to the last stream and stile

Thomas Hardy's Wessex vs the real-life Dorset: Which bits are real, which dreams, and which are exact to the last stream and stileThomas Hardy’s depictions of a fictional Wessex and his own dear Dorset are more accurate than they may at first appear, says Susan Owens.

By Country Life

-

Best Christmas light trails to see in 2021

Best Christmas light trails to see in 2021We know December is nearly upon us, as the season’s light festivals begin up and down the country — here's our pick of some of the best.

By Toby Keel

-

The English villages that are hotbeds of murder, intrigue and endless summer days — at least in the minds of novelists

The English villages that are hotbeds of murder, intrigue and endless summer days — at least in the minds of novelistsComforting yet complex, intriguing and alluring, the village setting is territory to which writers — and readers — will return again and again. Flora Watkins looks at how the customs, characters and communities of the English village have long sparked literary inspiration, from Jane Austen to Midsomer Murders.

By Flora Watkins