Who wrote 'God Save The King'? The extraordinary tale of the British national anthem

What are the origins of our national anthem? John Goodall investigates the extraordinary story behind both the tune and the words, as well as their influence on other nations.

In the early autumn of 1745, the future of Hanoverian rule in Britain hung in the balance. Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Stewart claimant to the throne, had landed in Scotland and occupied Edinburgh. On September 21, he also routed a government force close to the city at the Battle of Prestonpans. Regular soldiers were being hastily returned from Flanders to counter the threat and, in London, in response to the crisis, there was an outpouring of patriotic fervour. It found particular expression in theatres, where audiences responded enthusiastically to displays of loyalty to George II.

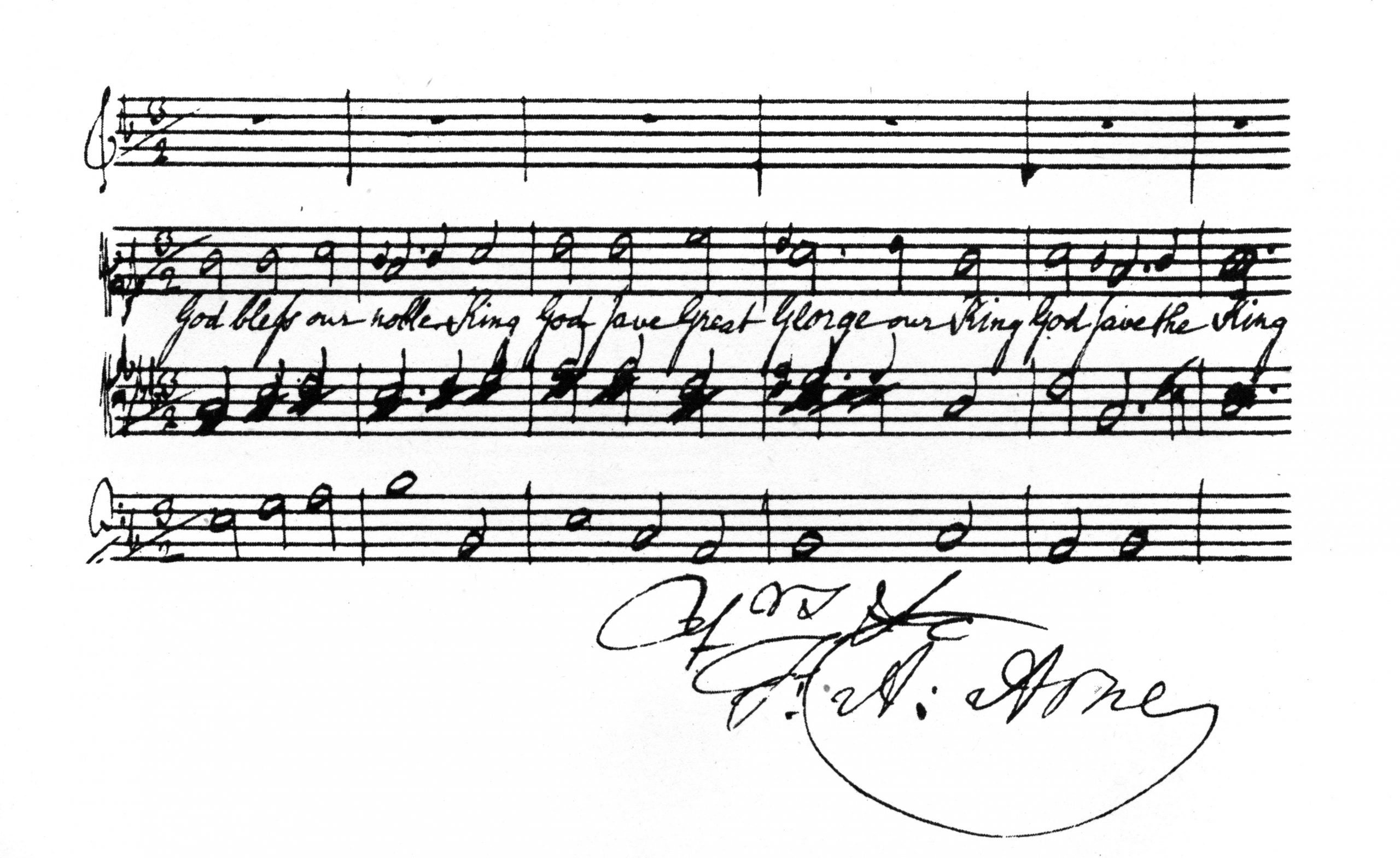

On September 28, 1745, therefore, a notice in the General Advertiser announced that Mr Lacy, Master of his Majesty’s Company of Comedians at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, had ‘applied for leave to raise 200 men, in defence of his Majesty’s person and government’. In the auditorium that evening, after a performance of Ben Jonson’s play The Alchemist, three celebrated singers of the day — Susannah Cibber, John Beard and Thomas Reinhold — stepped onto the stage and, with the support of a male choir, sang a traditional anthem with new words. It had been arranged by Thomas Arne, the composer who a few years previously had set a verse by James Thomson called Rule Britannia as the rousing finale of his 1740 masque Alfred.

The audience were delighted and, according to the Daily Advertiser of September 30, received the performance with ‘universal applause’, as well as ‘encores’ and ‘repeated huzzahs’, thereby illustrating in ‘how just an abhorrence they hold the arbitrary schemes of our invidious enemies and detest the despotic attempts of papal power’. Such was the success of the performance that, within two weeks, every play at both Drury Lane and Covent Garden was followed by the song. It began: ‘God Bless our noble king, God save great George our king…’ Now our national anthem, it has never passed out of the popular consciousness since.

There couldn’t be a greater irony to this anthem assuming its modern celebrity in 1745, because it is first recorded as being sung for James II, whose claim to the throne Bonnie Prince Charlie represented. Thomas Arne, the composer of the 1745 arrangement, was perfectly aware of this. When asked about the authorship of the anthem by the musicologist Charles Burney, he confessed that ‘he had not the least knowledge, nor could guess at all, who was either the author or the composer, but it was a received opinion that it was written for the Catholic Chapel of James the Second’. His mother, Mrs Arne (also the mother of the singer Susannah Cibber), reminisced that she had heard the song sung in the streets and playhouses ‘for King James II, in 1688, when the Prince of Orange was hovering on the coast’.

Of the origins of the tune, little can be said with confidence. Musicologists have offered a bewildering array of possible attributions, including to the composers Henry Purcell and John Bull, the dramatist Henry Carey or an anonymous source in a collection of carols called Melismata (1611). Nor is the history of the words much clearer. A version of the text was first printed in Thesaurus Musicus in 1744, but the expression ‘God save the King’ as a loyal exclamation has very deep roots indeed. It can be traced back in English at least to the Coverdale Bible of 1535 and in Latin much further. No less curious is the metre of the verse, which is as distinctive as a limerick with syllable lengths of 6:6:4:6:6:6:4.

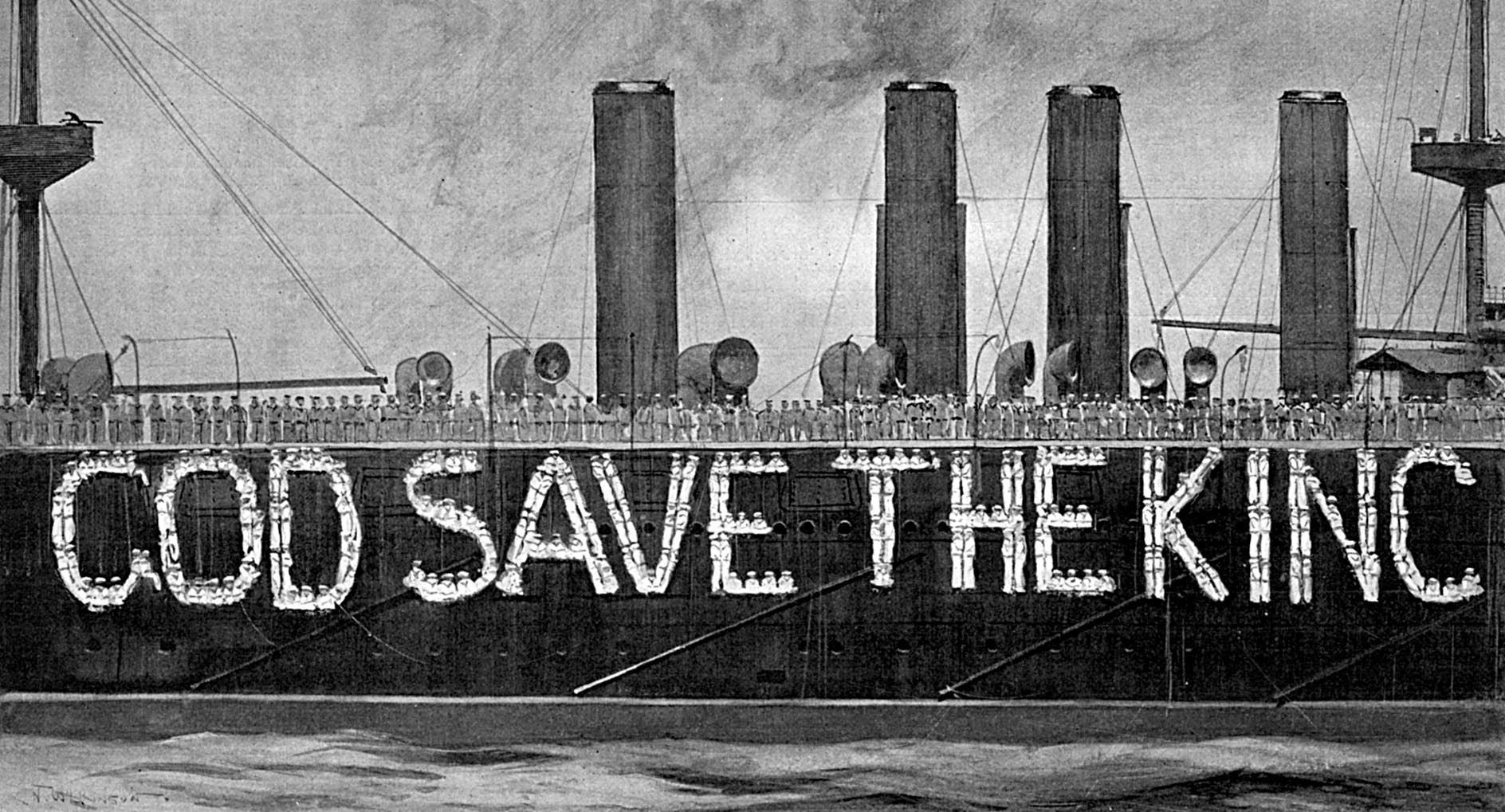

The subsequent history of this anthem is quite as fascinating as its origins. New versions of the words were circulating within months of its performance in 1745 and continued to be created for special events into the 20th century. Changes were also necessary to the original lyrics, because the names of some kings and queens — such as William or Victoria (and Elizabeth) — did not scan in the first two lines. Meanwhile, the tune itself became widely played, not only remaining popular at theatrical performances (George III was nearly assassinated during one rendition in Drury Lane in May 1800, the second attempt on his life in one day), but being sung in churches after services and countless other public occasions. It’s a tradition that was taken up in the 20th century by the BBC when it was played at the end of daily broadcasts (when broadcasts had an end).

Over the same period, it was also arranged by numerous composers, including Johann Christian Bach (as early as 1763), Weber, Brahms and Liszt. Beethoven famously wrote piano variations on the tune in 1803, reputedly announcing: ‘I must show the English what a blessing they have in God Save the King.’ (The Sex Pistols evidently thought otherwise in 1977.) Beethoven additionally wrote variations on Arne’s Rule Britannia. The title of the anthem enjoyed wide currency, appearing on everything from medals — one such struck in 1788 celebrated the recovery of the King from a bout of madness — to porcelain and the First World War marked a high point in the use of the phrase on posters and flags.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

What is not clear is when and how this anthem formally became our ‘national’ anthem, rather than merely a popular patriotic song. The idea of music that celebrated national identity is very old, at least in a military context. As early as 1610, Prince Henry, for example, the eldest son of James I, authorised the measure of the English March at Greenwich. It was subsequently endorsed in 1632 by his brother Charles I, who notes in an accompanying royal warrant that ‘the ancient custom of nations hath ever been to use one certain and constant form of march in the wars whereby to be distinguished one from another’. It then notates the authorised beat and instructs that ‘all drummers within our kingdom of England and principality of Wales exactly and precisely observe the same’. The Scots had their own march.

The widespread composition of national anthems from the late 18th century relates to such traditions, but is distinct and, to some degree, is actually born of the popularity of God Save the King. Joseph Haydn, for example, famously composed the Austrian anthem to the Emperor Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser in 1797 after having visited Britain and envying the English their ability to express loyalty through music. Many other countries have at one time or another simply borrowed the tune directly for a patriotic song and created their own words. In this sense, God Save the King — or, as we now knew it for so many years until September 2022, God Save the Queen — is not only a tune that has become a national anthem, it is the anthem that has actually defined the genre.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Jason Goodwin: The second, little-known verse of our National Anthem

Our spectator columnist comments on this past Remembrance Sunday.

Curious Questions: How did 'God Save The Queen' become Britain's National Anthem?

As patriotic songs come under the spotlight, Martin Fone takes a look at national anthems across the world.

Credit: Alamy

10 fascinating things you should know about the Shipping Forecast

From the tragedy which sparked its inception to the modern tweaks which have had listeners up in arms.

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.