Seven fascinating things we just learned about the Census

Ysenda Maxtone Graham is riveted by the facts and figures revealed in this engaging history of the Census.

There's nothing quite like a book that turns out to be an unexpected joy, and Roger Hutchinson's The Butcher, the Baker, the Candlestick-Maker (published by Little, Brown at £20) is exactly that.

With his eye for telling detail and his palpable fascination for the social history of the British isles, Hutchinson has made this history of the Census a highly readable delight. It’s the kind of general-knowledge-broadening book that will make you (if you read it) both more amusing at dinner parties and better on University Challenge.

In her review in the pages of Country Life magazine, Ysenda Maxtone Graham described it as a book which "felt like flying above your own country when returning from a holiday and looking down at the intricate patchwork of fields, farms, villages and towns which you suddenly feel a great love for."

Praise indeed – but rather than wax lyrical any further, we'll convince you via these seven extraordinary titbits which we couldn’t believe after reading his book...

A clergyman's son started it all by writing a magazine article

The Census was begun by a clergyman’s son called John Rickman, who proposed the idea in an 1800 article for The Commercial, Agricultural and Manufacturer’s Magazine entitled ‘thoughts on the Utility and Facility of ascertaining the Population of England’.

The population was underestimated by almost 300% before the first Census

The first Census was filled in by schoolmasters and overseers of the poor in every parish. Many didn’t complete it, so it’s ‘a hazy snapshot’, but the estimated population turned out to be 11 million — far higher than the four million some had feared.

You can't raise an army without knowing how many people you have

Prior to the first Census, no one had any idea how large or small the population was. The Napoleonic Wars made it a matter of urgency to know how many people needed to be fed and how many could be raised to arms if necessary. The fear in 1801 was that the population was diminishing (imagine that) and that Britain would therefore run short of fighting men.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Charlotte Brontë was officially unemployed

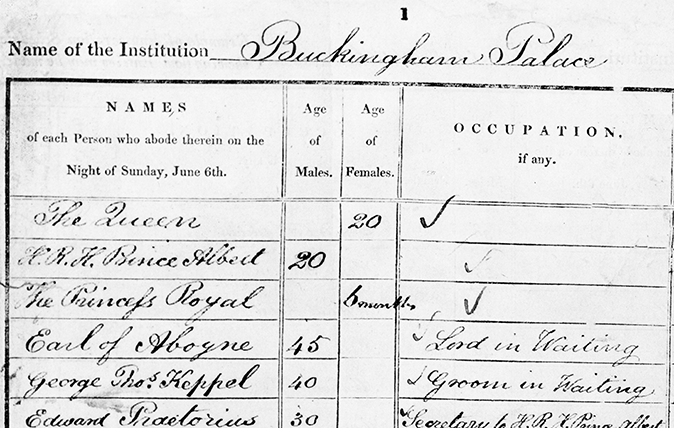

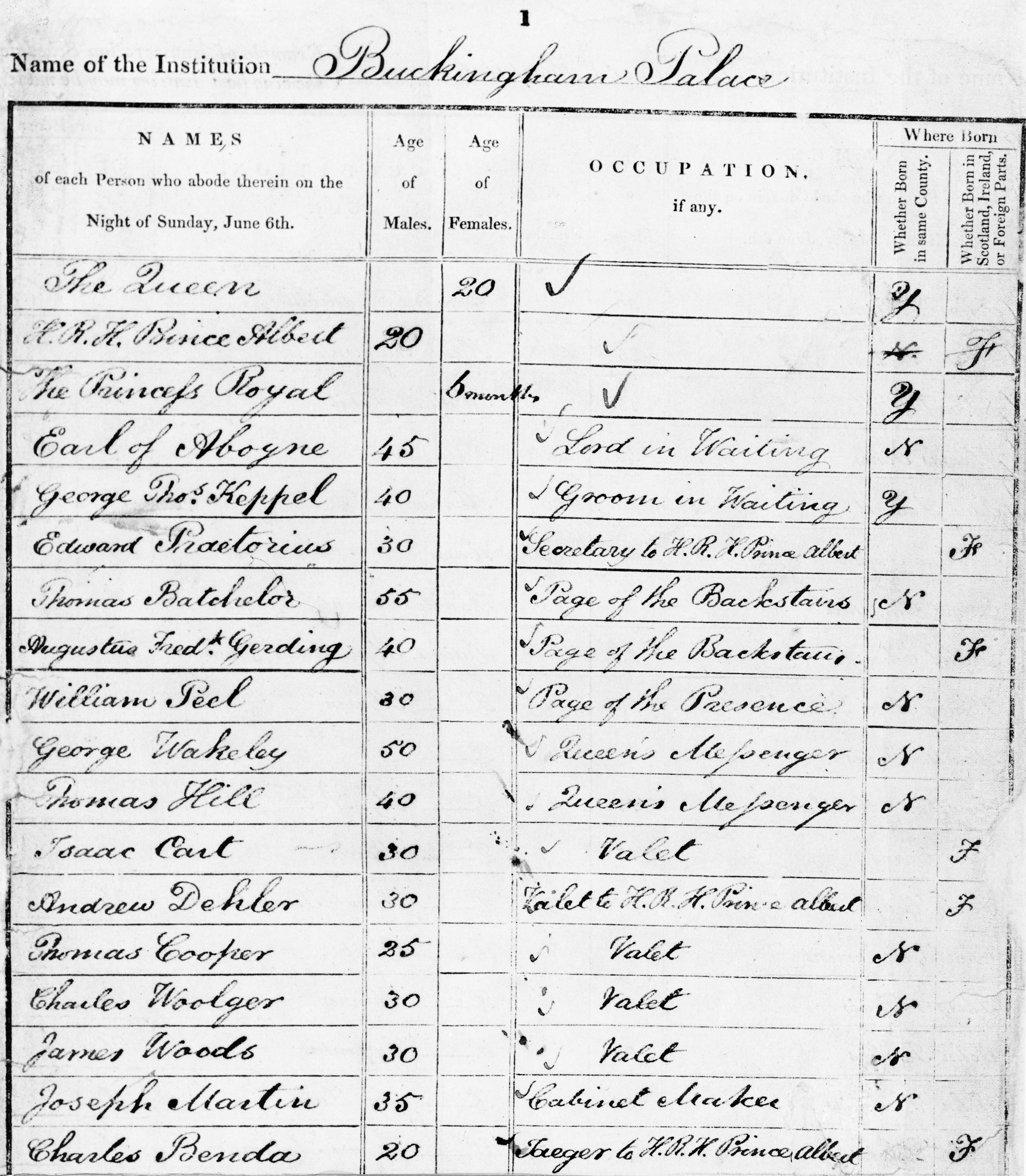

When Charlotte Brontë filled in her census return in 1851, even though she had been revealed as the author of Jane Eyre, she gave her ‘Rank, Profession or Occupation’ as ‘none’. She was in good company, however: as you can see from the picture at the top of this page – from the 1841 Census – The Queen also declined to fill in an occupation. Empress, perhaps?

You need to be careful how you describe your occupation

In Victorian England, it turns out that ‘seamstress’ was often used as a euphemism for ‘prostitute.’ No doubt there are people across the country who have put together what they imagine are highly respectable family trees who are blissfully unaware of this fact.

The year the Census didn't take place

The first British Census was in 1801 (unless you count the Domesday Book, which excluded most of Wales, all of Scotland and the tax-exempt cities of London and Winchester) and, since that date, all censuses have been in the year something-something-and-one – 1941 being the sole gap in the chain.

Dozens of fascinating-sounding jobs, and towns, have completely disappeared

Blabbers, crutters, flukers, learnmen, spraggers and whitsters are among the jobs that populate the pages of this book. Some occupations are no longer noted for very different reasons, however: in 1911, at the height of Suffragette campaigning, several hundred women gave their profession as ‘domestic slave’.

Our maps have similarly been deprived of colourful names, such as ‘the wapentake of Morley’, ‘the Hundred of Blackheath’, the ‘Lathe of Sutton-at-Hone’ and ‘the Rape of Chichester’. Just imagine typing some of those into the sat nav...

- - -

The Butcher, the Baker, the Candlestick-Maker by Roger Hutchinson is published by Little Brown, £20.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025Tuesday's Quiz of the Day blows smoke, tells the time and more.

By Toby Keel

-

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)With more buyers looking at London than anywhere else, is the 'race for space' finally over?

By Annabel Dixon