New Post-war public art exhibition

Featuring the work of leading 20th century sculptors such as Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Elisabeth Frink and Geoffrey Clarke, Historic England describes public art as a ‘fascinating yet forgotten national collection’

The role of public art in the post-1945 rebuilding of Britain and current attitudes to it are examined in the first major exhibition to be mounted by Historic England (HE), the quango created last year by the division of English Heritage. ‘Out There: Our Post-War Public Art’ opens next week (February 3–April 10) at Somerset House, London W2.

Featuring the work of leading 20th century sculptors such as Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Elisabeth Frink and Geoffrey Clarke, HE describes public art as a ‘fascinating yet forgotten national collection’, defining it as fine-art sculpture, concrete reliefs and fibreglass murals, found in both formal settings and everyday locations, such as schools, shopping centres and office plazas. The exhibition comes as HE announces 42 new listings of public sculptures, including Anthony Gormley’s Untitled (Listening Figure) in Camden, London, the first of his works to be listed, and three by Hepworth, including her Winged Figure, which can be seen on the exterior of John Lewis’s Oxford Street store.

‘Traditional statuary has been a feature of our townscapes since stone images of saints and martyrs appeared on the façades of medieval cathedrals,’ explains curator Sarah Gaventa. ‘Over the centuries, royalty, politicians and military heroes have been immortalised by statues, particularly in the “statuemania” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, the proliferation of public art after 1945 was rather different. The newly elected Labour government was committed to bringing art to the people and the London County Council [LCC] and the Arts Council created highly successful open-air exhibitions.’

The LCC’s open-air sculpture exhibition in Battersea Park in 1948 drew 170,000 paying visitors and was the first such event to show sculpture outside the art gallery. The Festival of Britain in 1951 provided another high-profile platform for a generation of artists. If sculpture had too often been the Cinderella of the Arts, the Festival, in the words of the late curator and critic David Sylvester, ‘provided her with glass slippers, a carriage and six white horses’.

It helped that the period could draw on a pool of talented artists who were enthusiastic about having their work displayed outdoors and committed to the late-Utopian zeitgeist of the 1940s. ‘Both Moore and Hepworth preferred their work to be in the landscape,’ says Miss Gaventa, ‘and Moore’s work became synonymous with postwar social ideals.’

Visitors to Battersea Park were allowed to touch Moore’s sculptures and the public commissioning of sculpture featured in wider initiatives, such as the creation of the New Towns —an entire room of the exhibition is devoted to Harlow, Essex, frequently cited as the most successful example. Its chief architect, Frederick Gibberd, declared that its Civic Centre ‘should be home to the finest works of art, as in Florence and other splendid cities’.

Moore’s Family Group was described by art historian Sir Kenneth Clark as ‘a symbol of a new humanitarian civilisation’ and Harlow also had works by Auguste Rodin, Frink, Hepworth, Lynn Chadwick and Antanas Brazdys. The Harlow Art Trust, set up in 1953, continues to commission works.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

However, more recently, there has been a loss of confidence in the value of public art. Miss Gaventa believes this set in during the recession of the 1970s: ‘Art in the public realm was seen as an unnecessary expense. There was also a change in artistic practice in the late 1960s and 1970s. Leading artists were less interested in producing a bronze on a plinth and the public felt less connected to more challenging abstract works.’

The exhibition ends at 1985, marking the 30-year cut-off date for which a structure can be considered for listing, but a final room examines different approaches to public art today. The period from 1945 to 1986 saw an estimated 2,000 works commissioned, but public art is still being produced and Miss Gaventa is emphatic that we still need it ‘like we need fresh air, Nature and sunshine. Today, there is a tendency towards more temporary public art commission than permanent ones. My favourite temporary piece was Richard Wilson’s Turning the Place Over (2007) from the Liverpool Biennial—art that made everyone stop and stare in wonder. As a permanent piece, Room by Antony Gormley, integrated into the Beaumont Hotel, Mayfair, is truly sculpitecture.’

Still, in the 40th anniversary year of Moore’s death, one wonders what the great man would have made of some recent efforts, such as Geoff Wood’s controversial Tree of Life, inflicted on Kirkby town centre in Lancashire and which some critics have cited as an example of the loss of direction and seriousness in modern public art.

Moore expert Peter Osborne of the Osborne-Samuel Gallery offers a more nuanced view, pointing out the eternal shock of the new. ‘It is essential to allow time for a public sculpture to adapt to its location,’ he says. ‘This does not happen immediately and there are many examples of public art initially loathed, then accepted, then wholeheartedly embraced by a community. What is required is, in the apt French expression, la patine du temps.’ Like Miss Gaventa, he thinks that many works acquire a greater gravity when placed outdoors. ‘Moore’s monumental bronzes amaze us not just because of what they are, but where they are, and our response to this juxtaposition of the manmade and the natural is critical to visual experience.’

He is concerned that many examples of postwar public art are being lost—one of Moore’s works has apparently been melted down. It says the price of scrap metal, the shortfall in funding for public bodies, redevelopment pressures and vandalism are among the causes and is asking for the public to come forward to help it track down lost pieces.

-

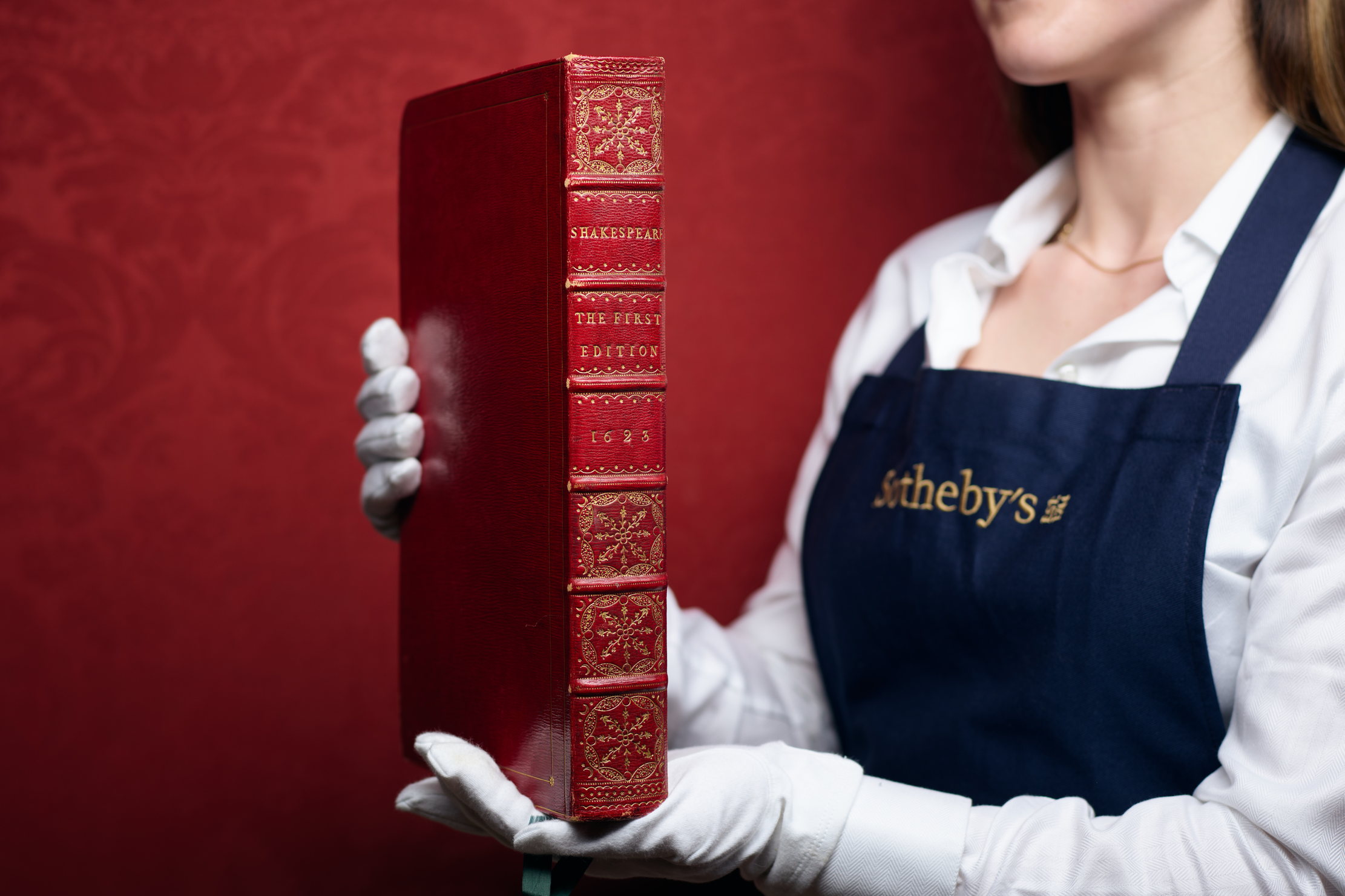

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow down

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow downThe glorious Andalusian-style villa is found within the Lomas de Marbella Club and just a short walk from the beach.

By James Fisher