New Benjamin Britten biographies

On the 100th anniversary of Benjamin Britten’s birth, Michael Hall reviews two new biographies of the composer

To order any of the books reviewed or any other book in print, at

discount prices* and with free p&p to UK addresses, telephone the

Country Life Bookshop on Bookshop 0843 060 0023. Or send a cheque/postal

order to the Country Life Bookshop, PO Box 60, Helston TR13 0TP.

Alternatively visit www.countrylife.co.uk/bookshop.

Biography

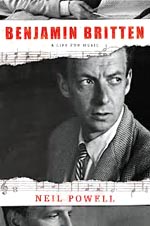

Benjamin Britten: A Life in the Twentieth Century Paul Kildea (Allen Lane, £30 *£24) Benjamin Britten: A Life for Music Neil Powell (Hutchinson, £25 *£20)

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

When Benjamin Britten turned 50 in 1963, he received a touching tribute from one of his closest friends and collabor-ators, the Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich. ‘When you and I are no longer here,' he wrote, ‘millions of ordinary people will still be celebrating your birthdays-your 125th, 150th and 200th birthdays. I foresee these jubilees and congratulate you in advance-you and your music.' This year, the 100th anniversary of the composer's birth, will see Rostropovich's prophecy fulfilled to a degree that would have astonished even him.

Britten's music will be played in opera houses, concert halls and churches all over the world, and in many more modest spaces, to delight exactly those ‘ordinary people' who have taken his works to their hearts in a way that none of his 20th-century peers, even Stravinsky, can quite match. Britten would have been delighted with this, but he would have been appalled by its inevitable consequence, the intense curiosity about his life that has prompted not one, but two large new biographies seeking to replace Humphrey Carpenter's trail-blazing life of the composer, published in 1992.

Although in commercial terms they are rivals, as biographies, they are complementary. Neil Powell's is a sensible, well-written book by an author who is, like Carpenter, a literary scholar: this is the biography to choose if you are new to Britten and want an introduction to his life. Paul Kildea is much more ambitious, as his subtitle suggests: he sets the story in a historical and musical context.

Both authors draw deeply on the six-volume edition of Britten's diaries and letters, published between 1991 and 2012. Edited with the co-operation of Britten's estate, its copiously detailed annotations make it, in effect, the composer's authorised bio-graphy. Although the existence of this monumental work, as well as the enormous secondary literature on Britten, makes it a challenge for a biographer to take an independent stance, Mr Kildea has not been deterred.

He is a musician and is not afraid to voice minority views on Britten's works. I was more startled by his dismissal of one of the composer's best-loved pieces, The Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, than I was by his assertion that the cause of Britten's death was syphilis an idea that has been persuasively challenged.

Mr Kildea unpicks the belief-encouraged by this notoriously thin-skinned composer-that Britten's early work was received with scornful disdain by the philistine interwar British musical establishment. He certainly got some cloth-eared reviews-what composer has not?-and often had to cope with low performing standards and too-short rehearsal times, but his prodigious talent brought him numerous commissions almost immediately. Mr Kildea demonstrates that even Vaughan Williams, for whom Britten almost never had a good word, was kindly and encouraging.

Mr Kildea is equally revisionist in his argument that Britten's crowning achievement, his operas, benefitted from collaborators who stood up to him. The most famous example is E. M. Forster, joint librettist of Billy Budd, whose criticisms of aspects of the way his words had been set forced Britten to revise some of the music. By the mid 1950s, fewer people dared to behave in this way, and the stage works suffered-Mr Kildea is sharp on the shortcomings of Myfanwy Piper's Turn of the Screw libretto. Both he and Mr Powell argue (I think rightly) that none of Britten's later operas equals Billy Budd, which was written when he was not yet 40. There are areas where I find Mr Kildea disappointing.

He tip-toes round Britten's pacifism, pushes his partner Peter Pears into the background to an undue degree-he seems simply not to like Pears very much-and, although he deals calmly with Britten's attraction to adolescent boys, he never quite gets to the heart of this difficult but central issue in the composer's life and art. These are significant weaknesses, but the book's many thoughtful insights make it a worthy successor to Carpenter's biography.

* Follow Country

Life Magazine on Twitter

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

The big reveal: A first look at Country Life's RHS Chelsea Flower Show stand

The big reveal: A first look at Country Life's RHS Chelsea Flower Show standInterior designer Isabella Worsley reveals her plans for Country Life’s ‘outdoor drawing room’ at this year’s RHS Chelsea Flower Show.

By Country Life

-

Schreiber House, 'the most significant London townhouse of the second half of the 20th century', is up for sale

Schreiber House, 'the most significant London townhouse of the second half of the 20th century', is up for saleThe five-bedroom Modernist masterpiece sits on the edge of Hampstead Heath.

By Lotte Brundle