Mervyn Millar, the genius puppet master behind War House and more: 'When there’s a puppet on stage, it does something different to your engagement with the storytelling'

Three men become one horse; four become one elephant. The life of a puppeteer is full of magic, discovers Katy Birchall, as she speaks to War Horse supremo Mervyn Millar.

For Mervyn Millar, the magic of puppetry isn’t conjured by the puppet, but the audience. ‘The puppet is clearly not alive, there’s no illusion — it’s a very honest invitation for members of the audience to imagine the character for themselves,’ explains the director of acclaimed puppetry company Significant Object.

‘When there’s a puppet on stage, it does something different to your engagement with the storytelling — it requires you to be active as you watch. The power of imagination manifested in the puppet is a lovely thing.’

A theatre director and puppetry specialist, Mr Millar has a long list of spectacular projects under his belt: from designing Newman, the robot that featured in the music video for Sir Paul McCartney’s single Appreciate to depicting the god of marriage, Hymen, for the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 2019 production of As You Like It. This enormous puppet measured almost 20ft high and 36ft wide. The latest production he has been involved with is The Magician's Elephant (of which more later).

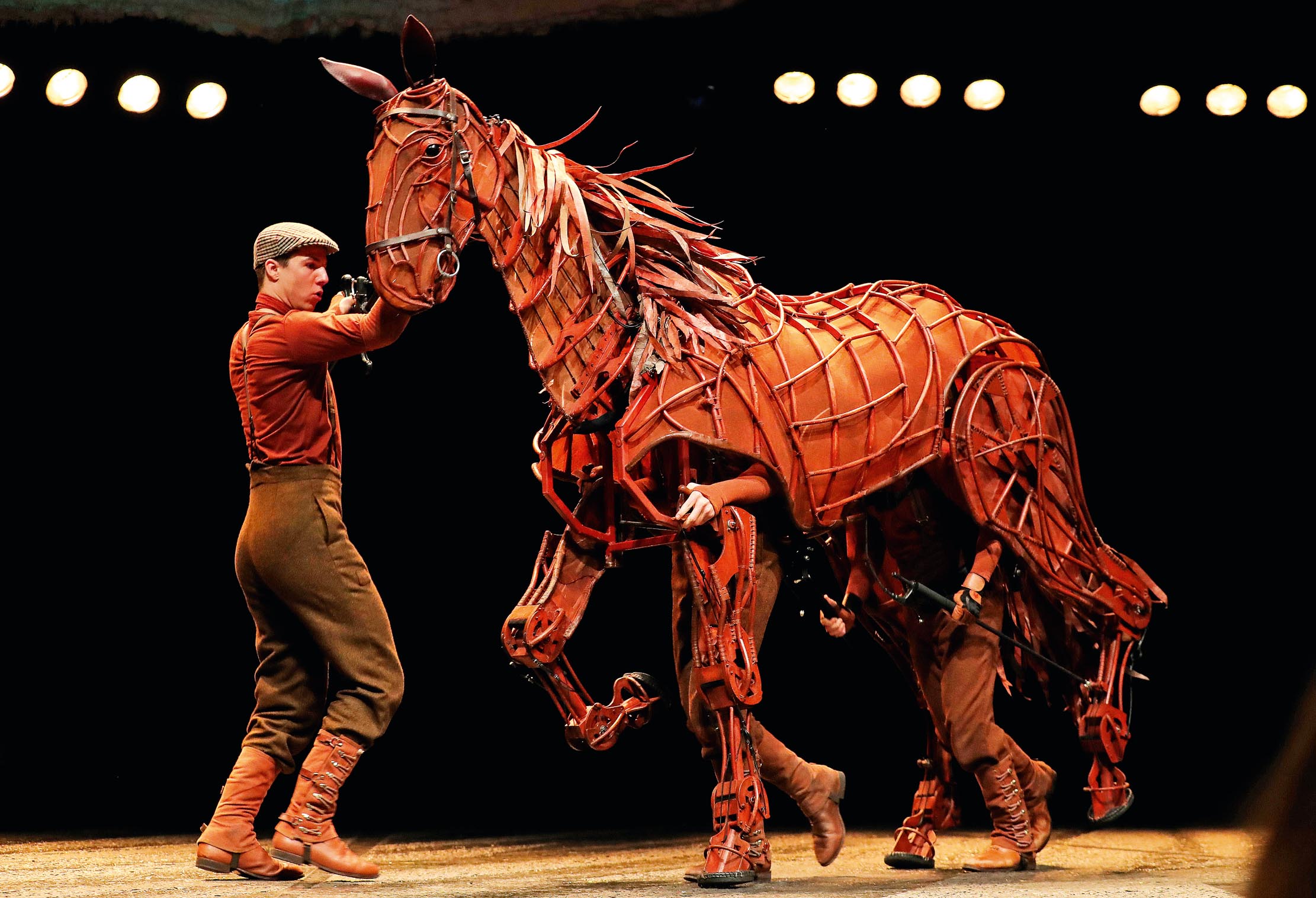

He is perhaps most well known for his work with Handspring Puppet Company to develop Joey, the equine protagonist in the National Theatre’s staggeringly successful adaptation of Michael Morpurgo’s War Horse. Telling the story of a horse’s journey from a peaceful life in rural England to the dark corners of the First World War, this remarkable production has captured hearts across the world.

‘None of us thought it was going to be successful — we thought the show would run for a few months,’ laughs Mr Millar.

‘It wasn’t the first popular show that included puppets, of course, but what it did differently was invite a puppet to be a central character. I’d worked with Handspring before and we’d done great puppetry, but in small venues to small audiences. The gesture of trust from the National Theatre to put it on the main stage was extremely brave.’

Mr Millar is thrilled that the triumph of War Horse has had a welcome knock-on effect for the craft. ‘It has underpinned a renaissance in high-quality puppetry in Britain and has been a big game changer for the way producers and directors think — and what they believe puppetry can do,’ he says. ‘There’s a growing talent pool of puppeteers in Britain: a lot of the War Horse performers have gone on to puppeteer for big motion-capture projects, such as the “Star Wars” franchise.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Having studied English at university before a master’s degree in theatre directing, Mr Millar is largely self-taught. ‘I was using puppets in my shows when training as a director and it didn’t seem strange to me — I simply hadn’t been taught not to use them,’ he recalls.

‘The more I worked with them, the more I found in them. One of the reasons I wanted to work in theatre is that it’s a world in which you won’t get bored; there are so many stories and styles you can tap into and puppetry is a total form of that — it’s got design, movement, singing, dancing. It’s all the theatrical arts in one image. Artistically, it’s very rewarding.’

A large component of Mr Millar’s job is teaching actors the technique required to bring his creations to life. Having written three books on the subject, he asserts that an audience establishes a connection with the marionette as a result of the instinct and skill of the puppeteer to generate expression. ‘You don’t need to carve a beautiful puppet to be able to learn, you can do puppetry with anything — sticks, paper, bits of cloth,’ he insists.

‘When you’re learning, using a simple object is more useful than struggling with a technically complicated puppet. Actors train to be the centre of attention, but, in puppetry, you’re teaching them to say “don’t look at me, look at this”. Like a musical-theatre or radio actor channelling emotion through a specific tool — voice or placement — the puppeteer uses a tool outside their body to communicate an emotional, grounded and honest performance. It’s very precise in how it is executed.’

In War Horse, Joey is operated by three performers: one each at the head, heart and hind. As well as the physical challenge of moving him fluidly across the stage, the puppeteers make the horse noises and control both technical and emotional indicators. Ear movements and tail flicks show the horse tuning into what’s going on around him; to indicate rhythm of breath, the performer at the heart bends his knees to move the body up and down.

‘We would often find that the heart of the horse, where the lungs are, is a great place for a big, emotional actor,’ discloses Mr Millar. ‘They use their whole body to breathe and show that shift of emotion in the animal’s body.’

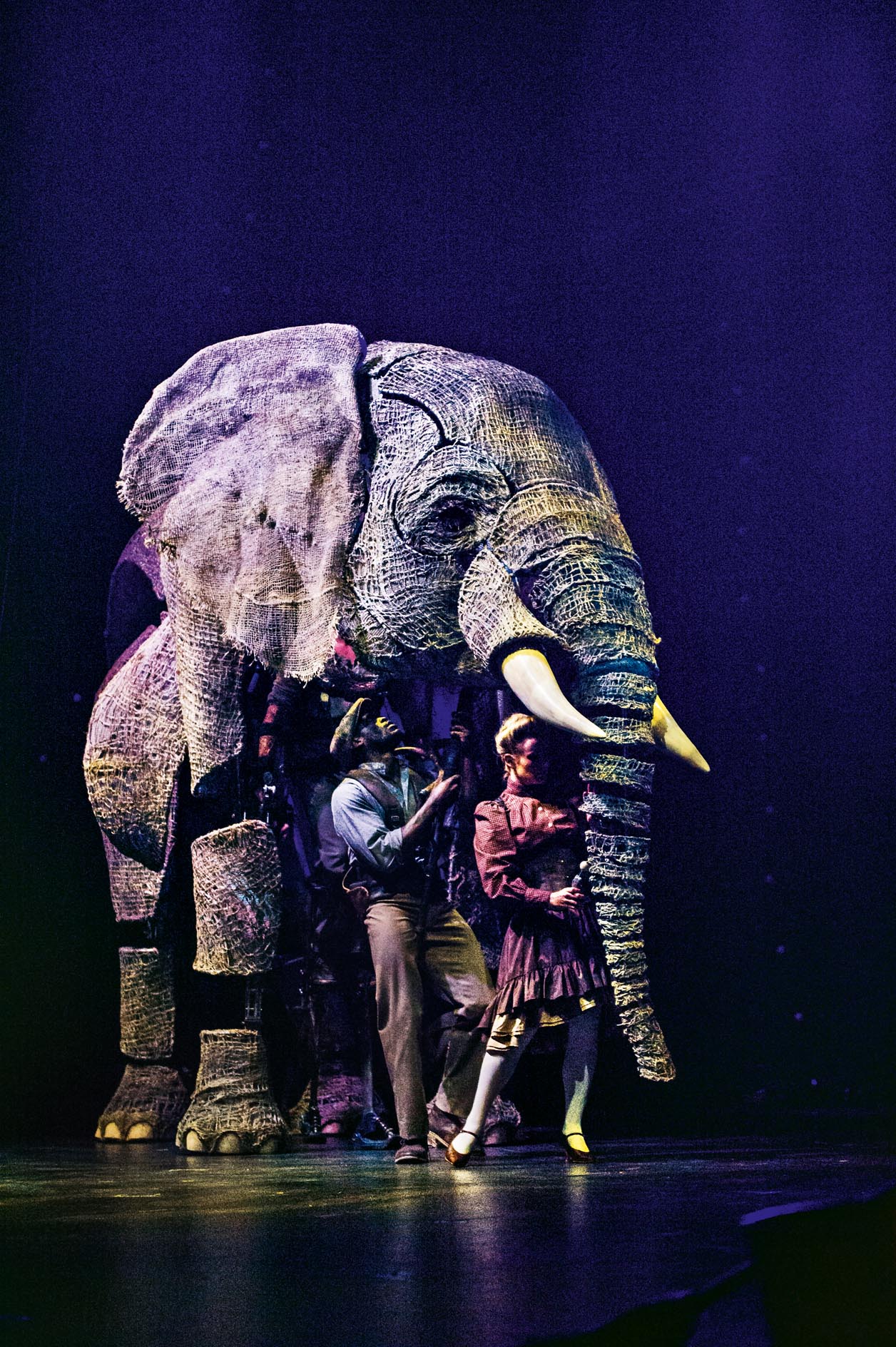

As with Joey, coordination between the puppeteers is paramount to one of Mr Millar’s latest constructs — a life-sized elephant for the Royal Shakespeare Company’s musical production of The Magician’s Elephant, based on Kate DiCamillo’s bestselling children’s novel.

‘The four performers playing the elephant have to put aside their egos and create one big character between them,’ he notes. ‘Their performance is completely in the moment, playing the feelings together. Perhaps it’s so pure because they don’t have the language to distract — their judgement, timing and sensitivity are incredibly moving.’

In collaboration with puppet designer Tracy Waller, Mr Millar began the process of developing the elephant by engaging with the character, allowing her personality to feed into research of the animal and how it moves.

‘Leaning on previous experience, we focused on the story we are telling, the mechanisms we could use and how to make it easier for the performer,’ he explains. ‘The elephant doesn’t need to do any galloping around or any stunts, so its work is very emotional — we’ve tried to give the performers as much range as we can to show changes in mood and intention.’

The actors performing on stage opposite the puppet are equally as key to its success, adds Mr Millar. ‘I can put as beautiful an elephant as I want on stage, but it’s the other actors believing in her that gives the audience the lead on how to do it. If you’re playing opposite an actor who doesn’t have that engagement, the audience loses the ability to imagine the elephant very quickly. All the actors are puppeteers in that sense — they all help to create that character.’

Constantly on the lookout for the next challenge, Mr Millar recently finished work on The Hatchling, an outdoor theatre project that’s been six years in the making, involving a giant dragon puppet hatching and making her way through Plymouth city centre, interacting with people and her surroundings as she goes, before taking flight across Plymouth Sound.

Operated by 14 puppeteers, the dragon was the size of a double-decker bus, with an unfurled wingspan of some 66ft — a jaw-dropping spectacle well worth a watch on YouTube. ‘My favourite conversation of any project is the first one, when the directors say, “Do you think we can do this?” I very rarely say no,’ Mr Millar concludes. ‘I’m attracted to the impossible ones.’

Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of ‘The Magician’s Elephant’ runs in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, until January 1, 2022 — www.rsc.org.uk; www.significantobject.com. Circus 1903 (for which Mervyn also designed the puppetry) is at Southbank Centre from 16 Dec – 2 Jan — circus1903.com.

‘It’s all about wonder and to look, to be able to ponder’ – the story behind spectacular nativity scenes

Each December, a newborn baby takes centre stage in Nativity scenes throughout the land. Julie Harding meets those responsible for

Barry Cryer: An anecdotal stroll through decades of comedic performance on stage, radio and TV

The peerless Barry Cryer on self-obsessed humour, an eczema cure and Boris Johnson.

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric villageA romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

By Ben Lerwill