A doll's house fit for a queen: How Lutyens created a Lilliput for Queen Mary

A miniature palace designed by Lutyens and promoted by Country Life offers a fascinating perspective on the 1920s, as Gavin Stamp explains.

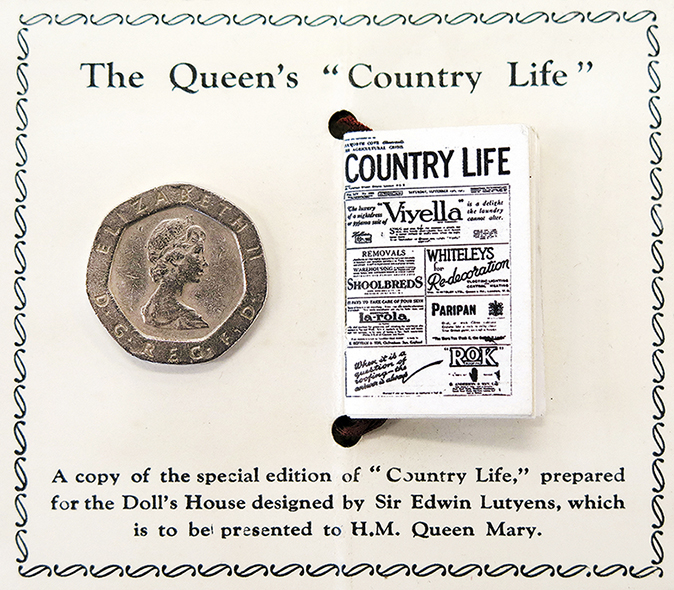

Lying on a table in the library in Queen Mary’s Doll’s House in Windsor Castle is, among other contemporary journals, a miniature edition of Country Life (Fig 4), no wider than a 10p coin and dated September 19, 1923. its presence reflects the importance of the magazine, then as now, as well as the connections between Country Life and the Doll’s House project.

Sir Lawrence Weaver, then Architectural Editor, was co-editor with A. C. Benson and E. V. Lucas of the two-volume study of the model building and its decoration and contents and, crucially, director of the UK exhibits at the British Empire Exhibition held at Wembley in 1924 at which the Doll’s House was first exhibited. And, of course, Weaver, along with the magazine, had long been the promoter of the genius of the architect who designed the 5ft-high timber structure: Sir Edwin Lutyens.

Country Life gave Lutyens’s unusual building suitable coverage. in 1924, Christopher Hussey published two rather arch articles in the manner of Jonathan Swift to describe in detail ‘The Palace of Their Majesties The King and Queen of Lilliput’, noting how Lutyens, ‘the King’s Chief Architect, had, with the utmost ingenuity, designed; less to be a perpetual Habitation for their Majesties, than for a grand Example, to all coming from other Lands, of the Arts, Domestic Uses and Applied Sciences of Lilliput at that time’.

‘My only regret,’ concluded Gulliver/ Hussey, ‘is that, owing to my unfortunate size, I have been unable to get inside it. (Whereat everybody laughed heartily.)’ He also noted how ‘News sheets lay upon a table, among them a journal said by many to be the nob- lest in Lilliput, named C------y L—e’.

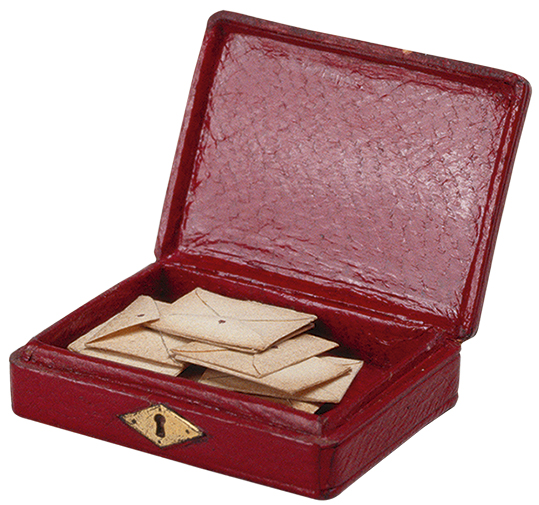

The Doll’s House was originally the brainchild of Queen Victoria’s grand- daughter, Princess Marie Louise, conceived in 1921 as a nation’s gift to the Queen in recognition both of her role as figurehead during the First World War and of her acquisitive passion for miniature objects. Lutyens entered into the project with enthusiasm and the contributions of a wide range of artists and craftsmen were enlisted. Murals, for instance, were painted by such as William Nicholson, Gerald Moira and William Walcot. British manufacturers gave accurate models of their products, including a ministerial despatch box (Fig 5).

Few refused, although Virginia Woolf declined to contribute to the miniature library, as did George Bernard Shaw, ‘in a very rude manner’. Sir Edward Elgar reacted with fury to the request to give a miniature score, exclaiming (privately): ‘We all know that the King and Queen are incapable of appreciating anything artistic... But as the crown of my career I’m asked to contribute to— a Dolls’ House for the Queen... I consider it an insult for an artist to be asked to mix himself up in such nonsense.’

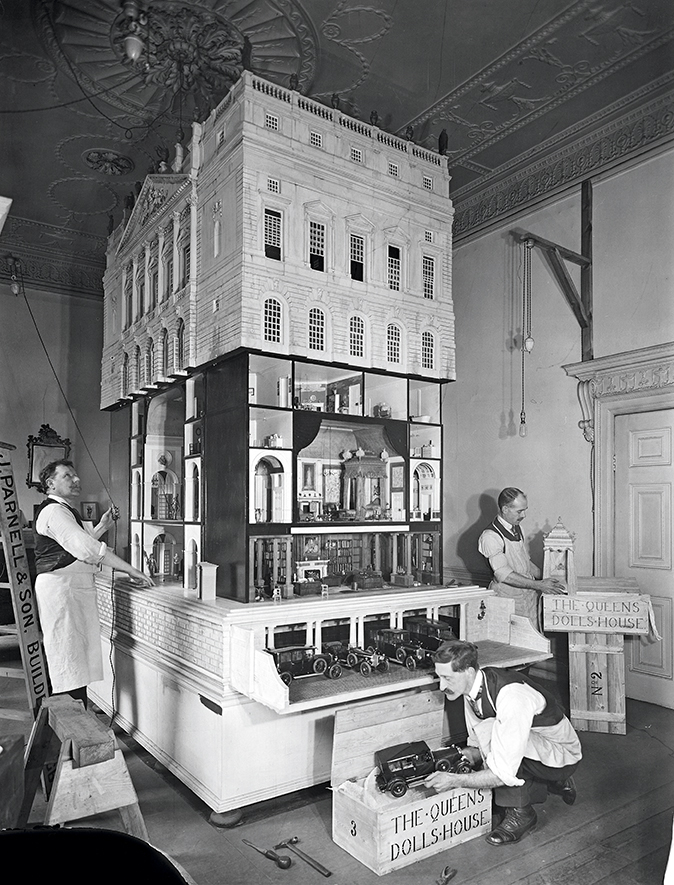

Queen Mary’s Doll’s House and its contents were assembled in Lutyens’s own drawing room (Fig 2) in his house in Mansfield Street, W1, before being exhibited at Wembley. It was then shown at the 1925 Daily Mail Ideal Home exhibition at Olympia before being installed in a room, specially adapted by Lutyens, in Windsor Castle, where it has been ever since.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Visited by hundreds of thousands every year, it is now rather taken for granted as part of the national and royal heritage, yet what a weird thing it really is. And what a strange reflection it was on the state of Britain that, at a time of slow recovery from the ruinous catastrophe of the First World War, some 1,500 individuals should have come together over a period of 2½ years to create, with great skill, effort and expense, a large doll’s house that was never intended to be played with.

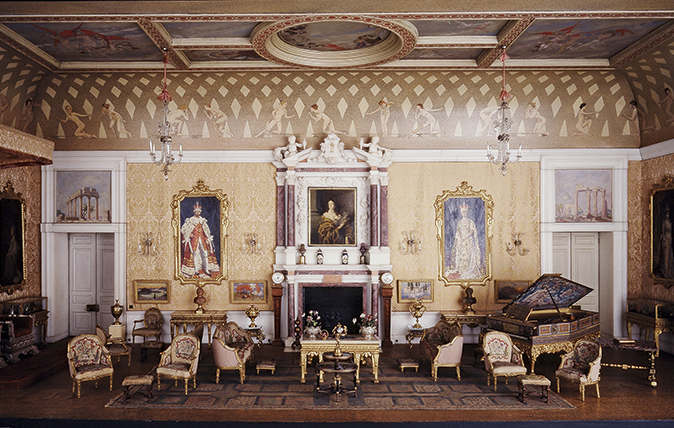

Part of the appeal of this Doll’s House is that not only are all the contents more or less accurate to a scale of 1:12—one inch to the foot— including tableware (Fig 6), seating and portraiture (Fig 3), but that mechanical devices actually work. The large gilded sash windows (like those at Chatsworth) are apparently hung on cords from pulleys and will slide. There are two electrically powered Waygood-Otis lifts that work in addition to the carefully designed staircases (Fig 1). The plumbing in the King’s and Queen’s Bathrooms— wonderful examples of what would become the inter-war Cult of the Tub—will drip and drain away water. And there is a wind-up gramophone that can play miniature HMV records of Rule Britannia and God Save the King.

However, no child or adult—not even royalty—can ever be allowed to play with these things, read the books in the library, or, indeed, penetrate beyond the glass box that protects the model. Many of its marvels must simply be imagined.

The appeal of models is perennial, of course, as anyone who played as a child with a doll’s house or train set or made Airfix aeroplane models will know. There is, however, something a little disturbing about the time and effort expended on this project. Given the context of its time, with Britain and her Empire exhausted by the war, uncertain about the future and facing severe economic problems, it suggests a refusal to face reality. Indeed, it smacks a little of infantilism.

Perhaps this is not surprising when Lutyens himself was notorious for his childish humour, his jokes and terrible puns; he was the ‘eternal child’ as E. V. Lucas called him. It is surely not irrelevant that, before the war, he had designed the sets for the first stage production of Peter Pan for his friend J. M. Barrie, that exemplar of arrested development, and, as Lutyens’s daughter Mary later recalled: ‘It was through our night-nursery window at Bloomsbury Square that the Darling Children flew to the Never Land.’

According to Benson, one purpose of the Doll’s House was ‘to present to Her Majesty a little model of a house of the twentieth century which should be fitted up with perfect fidelity, down to the smallest details so as to rep- resent as closely and minutely as possible a genuine and complete example of a domestic interior with all the household arrangements characteristic of the daily life of the present time’. However, it was no such thing.

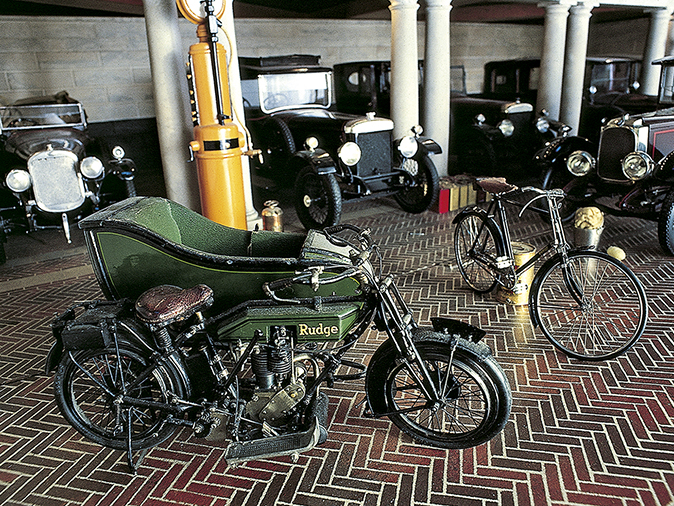

Although it had better and more modern services—as well as a much larger garage (Fig 7)—than most contemporary new houses, the Doll’s House was a profoundly reactionary piece of architecture, more typical of the Edwardian age than of the 1920s, and designed to be run by a large domestic staff. There is absolutely no hint here of the Modernism that was affecting architecture over so much of Continental Europe. Perhaps this is not surprising when Lawrence Weaver could write, in 1922, that, ‘a new method of design is incredible, simply because it is not feasible’.

There is more. A strange fact about the British Empire Exhibition was that, although the Doll’s House was conspicuous and much visited, the grand new capital for British India planned by Lutyens before the war was hardly noticed and represented only by a small model.

One reason why Lutyens was so committed to the Doll’s House project was not only that there was little building going on in the early 1920s, but also that his greatest work, the palace for the Viceroy in New Delhi, was beset with political and economic difficulties. Perhaps, as the American historian Timothy M. Rohan has claimed, thinking of the original project before he was obliged (so brilliantly) to Orientalise it: ‘The Doll’s House is a proxy, substitute or surrogate for the Classical Viceroy’s House that was never built in New Delhi.’

Not only can the Doll’s House not be played with, it is not really a doll’s house at all as there are no dolls in it. This was because, as Benson explained, ‘a doll is not a human being in miniature at all, it never produces the slightest illusion of being a real person magically made small’. Queen Mary’s Doll’s House should, therefore, really be regarded as a superb architectural model, comparable with the Great Model for St Paul’s Cathedral by Lutyens’s hero Wren or the model of his own unexecuted design for Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral— both of which have carefully detailed (if unfurnished) interiors.

But this begs the question as to what sort of architecture the Doll’s House represents. It is not a royal palace— there are no grand reception rooms or ballrooms—nor is it the sort of country house in the design of which its architect had excelled. Perhaps, in its disciplined compactness, governed by its precise rectangular plan, it is a sort of free-standing aristocratic town house such as might be imagined in St James’s.

The late Sir John Summerson wrote that the Doll’s House was ‘one of the few really dull things Lutyens has done’. This is surely true. The exterior of the house, although perfectly proportioned, is derivative, closely modelled on those by Inigo Jones at the Banqueting House in Whitehall and Wren at Hampton Court. There are here none of the games Lutyens could play with the Classical orders, none of his Mannerist tricks.

Oddly enough, the miniature pavilions or ‘architectural cupboards formed as orangeries’ that Lutyens placed on the walls of the room containing the Doll’s House are more interesting and architecturally inventive, with projecting free-standing columns and rooftop fountains like those on Viceroy’s House.

Nevertheless, there are ways in which Queen Mary’s Doll’s House was genuinely original and without precedent. After all, the conventional doll’s house usually has a single façade, treated as hinged doors to open to expose the interior. The exterior of Queen Mary’s Doll’s House, in contrast, is a sort of shell that is hoisted up in the air, like a suspended font cover, to reveal the interior spaces.

Furthermore, whereas a doll’s house is usually only one room deep, exposed on one side only, the Windsor Doll’s House is truly three-dimensional, like a real house. Just as, at about the same time, Lutyens took the unidirectional Roman triumphal arch and developed it along two cross axes to create the extraordinary and unique geometrical complexity of the Memorial to the Missing of the Somme at Thiepval, so the Doll’s House is designed to be seen on all four sides.

The plan is clever, complex and practical: a pattern of rooms large and small. The spaces and how they connect can be appreciated and it can easily be imagined how the King and Queen of Lilliput, together with their servants, can move though the rooms on each floor and up and down between them.

As an historic building (is it listed? it should be, at Grade I), Queen Mary’s Doll’s House tells us much about the society that created it. As an exercise in three-dimensional planning, combined with the use of fine materials and sophisticated interior decoration, it still has much to teach us. It may be rather conservative as architecture, but, as an exceptional fantastic artefact, it is nonetheless enchanting: a great wonder.

Gavin Stamp