J.R.R. Tolkien: The life and times of the lord of the books

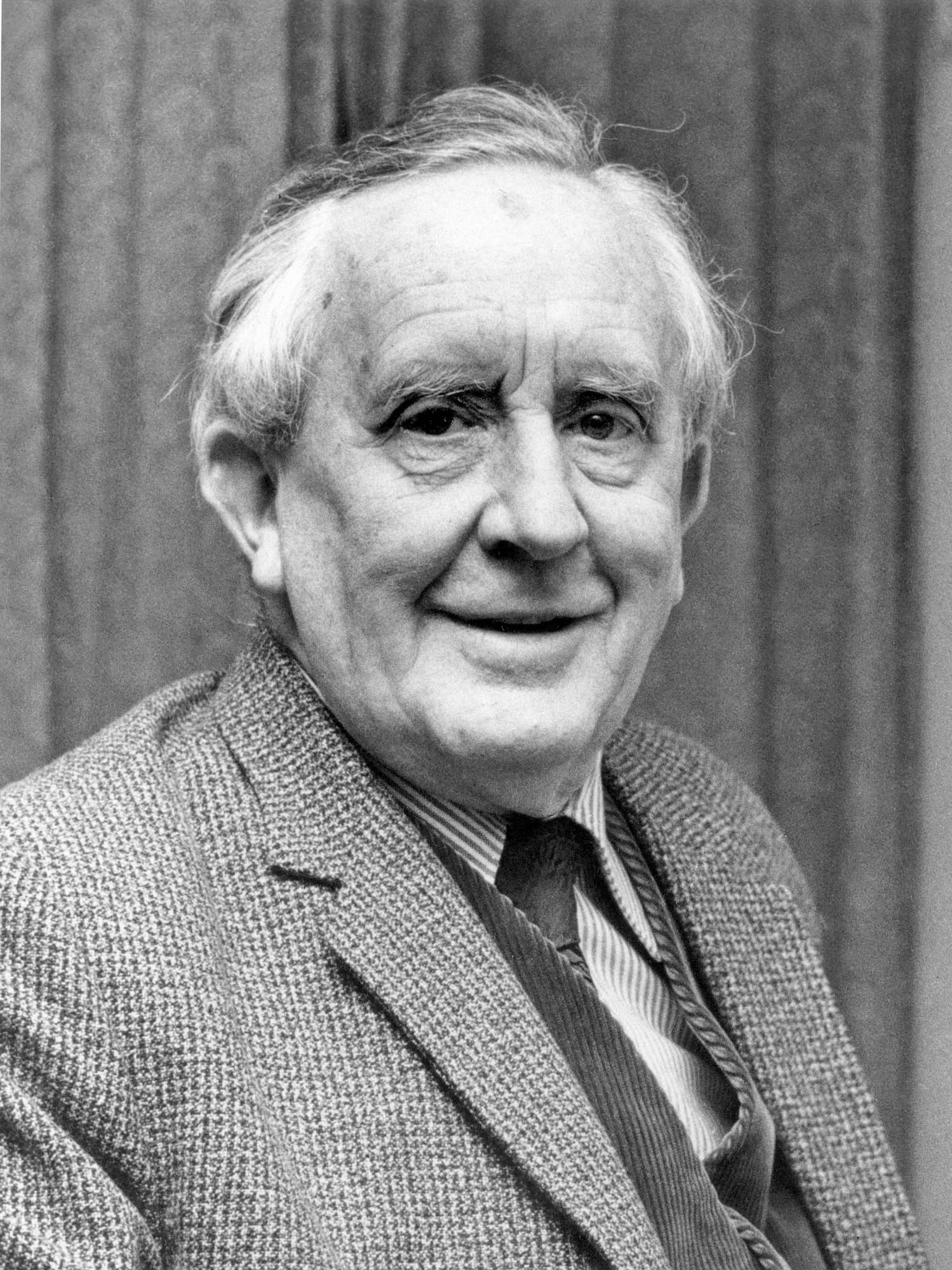

From a sentence born of an exhausting teaching job, J. R. R. Tolkien crafted a series of fantastical novels that, 50 years on from his death, still loom as large in our imagination as Sauron’s all-seeing eye, says Matthew Dennison.

Sometimes, early in the morning, with a jumper or an old coat pulled over my pyjamas, I slip out of a side gate and along the drive to stare at the point where there is a bend in the valley. Bracken-covered hills rise ochre, grey and green towards the sky and, in the distance, beyond broad fields of cattle, a lane bisects the landscape, winding out of sight.

More than once, at the end of the summer, bare feet in gumboots, drinking deep draughts of sharp, pure air, I have thought of Bilbo Baggins leaving Beorn’s hall in The Hobbit. Of that heavy-hearted departure on the part of our affable, but not excessively bold hero, Tolkien tells us ‘there was an autumn-like mist upon the ground and the air was chill, but soon the sun rose red in the East and the mists vanished’.

In my out-of-the-way Welsh hills, early-morning mists and rose-red dawns are a familiar sight. Whether it’s true or not, I’m happy to believe the statement of an elderly local, who told me that Tolkien spent holidays in the house in which I now live, surrounded by mist-coiled hills and densely green fields that, for me, resemble the landscape of the Shire, a terrain of springs and mountain streams, even, within driving distance, ancient barrows, that also recall Tolkien’s translation of the Old English poem Beowulf, which he completed in the 1920s, a decade before Bilbo made his debut.

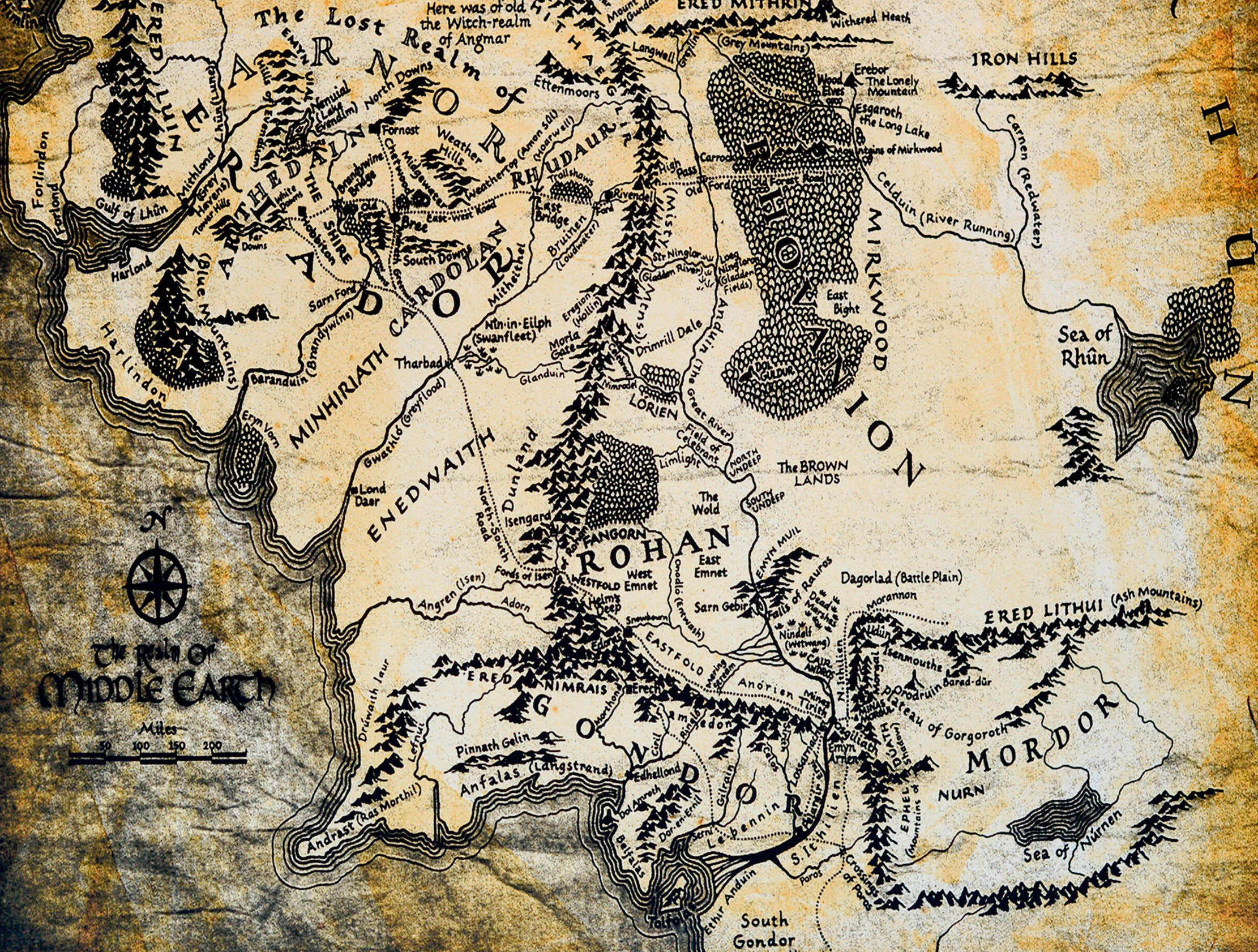

The bucolic dimension in the work of Britain’s best-loved fantasy writer is sometimes overlooked. Tolkien’s novels, which include The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy, are richly descriptive. Landscape is vividly evoked, its features sharply delineated, like the thicket amid the glens of the Morgai into which, in The Return of the King, Sam and Frodo fall: there, memorably, ‘the thorns and briars were as tough as wire and as clinging as claws’. Tolkien notes, too, the passage of the seasons and their changes: in late spring, Bilbo looks in vain for something to eat, ‘but the blackberries were still only in flower, and of course there were no nuts, not even hawthorn-berries’.

The same attention to detail is clear in many of the sketches Tolkien made in coloured pencils throughout his life, such as an image from 1928 of a copse of tall, thin trees growing within sight of the sea at Lyme Regis in Dorset: each finger of fern leaf is crisp, the tree trunks minutely patterned to capture the uneven contours of bark. The author, who loved surviving remnants of the language and culture of Anglo-Saxon England, was equally in thrall to the precious remaining unspoiled landscapes of these ancient islands. His pictures, like his writing, celebrate his love of trees, flowers, the countryside and, occasionally, rural architecture. Townscapes are rare.

Born in Bloemfontein, South Africa, on January 3, 1892, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, known in his family as ‘Ronald’, lived in England from early childhood, following the death of his father, Arthur, in 1896, until his own death in 1973. The relations of his mother, Mabel, were from the West Midlands, and artistic; in their new home in the then rural hamlet of Sarehole, which later inspired his illustration of Hobbiton-across-the-water, Mabel taught her child botany and to paint and draw.

Although Tolkien may not have been old enough to recognise it at the time, the West Midlands showed him all too starkly Nature’s fragility. Whereas Sarehole remained convincingly rural, nearby Birmingham, where he later went to school, was uncompromisingly industrial, its skyline blackened by smoke, many of its streets crowded, noisy and dirty.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

For the rest of his life, his preference would be for a vision of pre-industrial England. To his publishers, he described the Shire, home of the country-dwelling Hobbits, as ‘more or less a Warwickshire village of about the period of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee’. Referring to the kingdom established in the Midlands after the Roman occupation of Britain, he would tell his youngest son, Christopher, that he considered himself ‘Mercian’.

Over the misty mountains

Although Tolkien himself was innately conservative, both in social outlook and his deeply held orthodox Catholic faith, in the 1960s his fantasy fiction became essential reading for a generation of rebellious Baby Boomers, especially in North America. Tolkien’s surprise perhaps overlooked the perceived prevalence of a taste for hallucinogenic plants among residents of the Shire.

Mabel Tolkien died of diabetes in 1904, leaving 12-year-old Ronald feeling, he remembered, ‘like a lost survivor in a new alien world after the real world has passed away’. As did many ‘lost’ children, he sought solace in imaginative escape — in his case, in northern mythology, inspired by a story he had encountered in Andrew Lang’s Red Fairy Book, of a dragon-slaying hero called Sigurd. He read the 13th-century Old Norse Völsunga saga, in a translation by William Morris, with its account of a golden ring made by dwarves, stolen, then cursed. He also read Joseph Wright’s Primer of the Gothic Language.

An aptitude for ancient and modern languages — Gothic, Finnish, Welsh, Latin, Greek and Hebrew — came to shape his own written style, as well as exposing him to compendia of stirring and dramatic storytelling. Later, he would write: ‘Things that are uncomfortable, palpitating and even gruesome, may make a good tale.’ It was a lesson he absorbed as a teenager, discovering the Norse legends that would remain an abiding love and colour much of his published work. From his study of Finnish and Welsh emerged his version of ‘Elvish’ language; he claimed he had based his Dwarvish language on Hebrew.

Tolkien was in his early thirties when, in 1925, he won a professorship at Oxford: for the next 20 years, he would remain professor of Anglo-Saxon, although he discovered he had little appetite for teaching, describing it unequivocally as ‘exhausting and depressing’. How fortunate that this should have been the case.

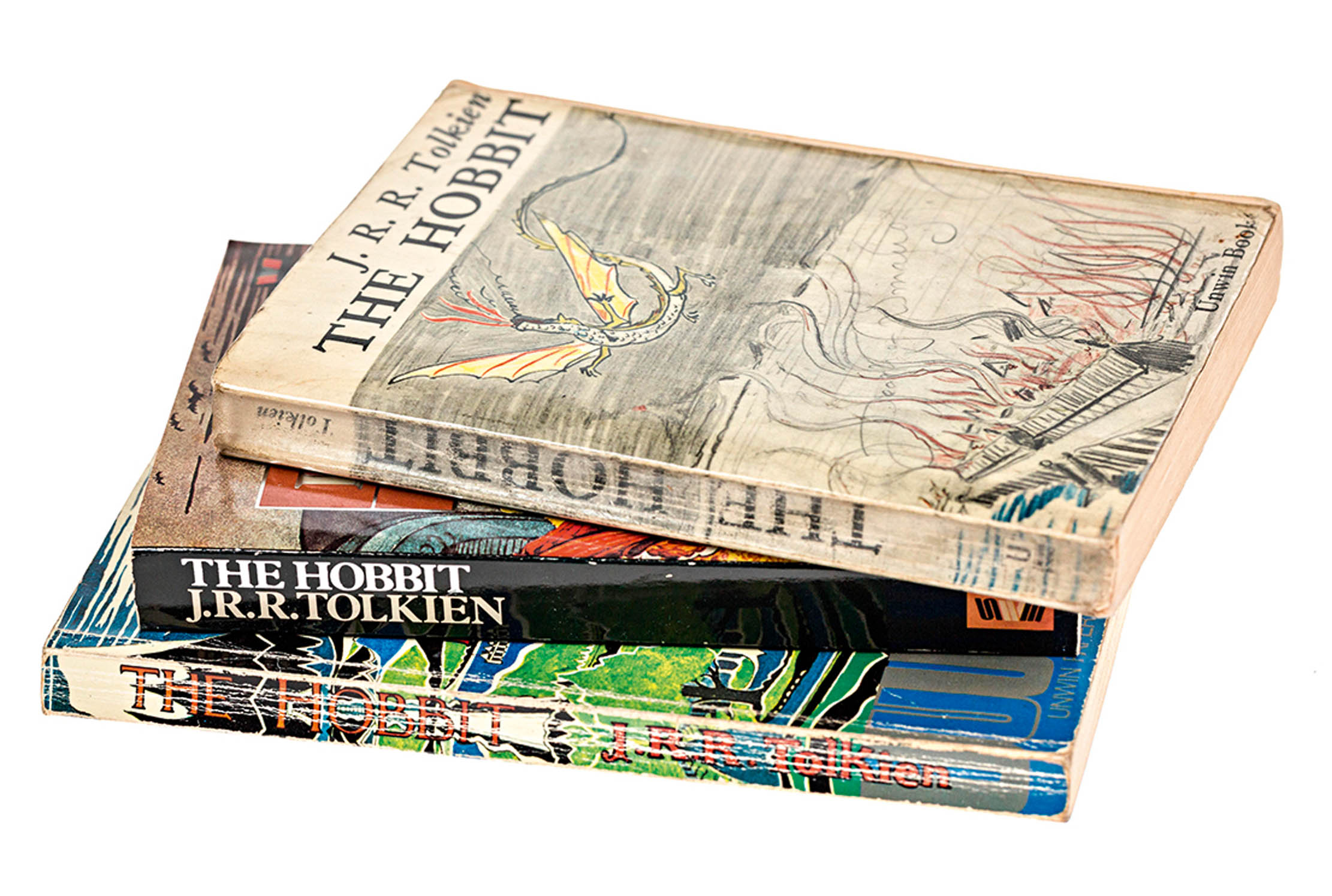

In a moment of flagging spirit, marking examination papers, he wrote what would become one of the best-known first lines in English: ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.’ The resulting novel was published in 1937 to instant acclaim and led, at its publisher’s suggestion, to a sequel, long in gestation, the trilogy of novels that make up The Lord of the Rings. All four novels display their author’s remarkable ability for absorbing wide-ranging influences in the creation of a new mythology, with roots not only in Norse and Celtic traditions, but in legends of Alexander the Great and even the work of Plato. Fellow Oxonian C. S. Lewis praised The Hobbit’s ‘happy fusion of the scholar’s with the poet’s grasp of mythology’.

Tolkien had married Edith Bratt in the spring of 1916, before his departure to fight in the trenches of the First World War. The couple had met when he was 16; together they had three sons and a daughter, Priscilla, the last born in 1929. Theirs was a close and loving family life, centred on a devoted partnership between Tolkien and his wife, whose ‘raven’ hair and bright eyes delighted and inspired him for more than half a century. He would outlive Edith by less than two years, dying on September 2, 1973; they lie together under a single gravestone. At his death, much of Tolkien’s work remained unpublished.

It is tempting to see parallels between Tolkien’s last years and Bilbo’s return to the Shire. ‘He took to writing poetry and visiting the elves; and though many shook their heads… and few believed any of his tales, he remained very happy to the end of his days.’

The life and times of J. R. R. Tolkien

January 3, 1892 born in Bloemfontein, South Africa, to Arthur and Mabel Tolkien

1895 Mabel Tolkien and her sons Ronald and Hilary return to England, after Arthur’s death, but she dies in 1904

1911 Tolkien goes up to Oxford. After changing to English Language and Literature, he is awarded a First. He studies philology, exploring historical developments of language

1916 Marries Edith Bratt. In the same year, as a second lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers, he leaves England for France, returning after four months with trench fever, an illness that recurs over the next two years

1917 Begins writing The Silmarillion

1918 Becomes Assistant Lexicographer on the New English Dictionary, mostly working on the history of words of Germanic origin beginning with W

1920 Appointed Reader in English Language at the University of Leeds

1925 Becomes Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford; collaborates on a translation of the Middle English poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; invents ‘Elvish’ languages

1926 Meets C. S. Lewis. Later, Tolkien writes: ‘The unpayable debt that I owe to him was not influence but sheer encouragement. He was for long my only audience.’ In the same year, writes, but does not publish, a translation of Beowulf

1928–29 Works on an archaeological excavation on the site of a Romano-Celtic temple, at Lydney Hill in Gloucestershire, known as Dwarf’s Hill. Ancient folklore connects the area with dwarves and a labyrinth of holes and tunnels runs through the hill

1929 Tolkien’s fourth and last child born; now he has John (1917), Michael (1920), Christopher (1924) and Priscilla (1929)

1930s First meetings of the informal literary discussion group known as the Inklings, often in the Eagle and Child (or Bird and Baby) pub. Fellow members include C. S. Lewis, as well as Chaucer scholar Nevill Coghill and Lord David Cecil

1937 The Hobbit is published. Tolkien cites Beowulf as one of its ‘most valued sources’. Within a month of publication, publisher Stanley Unwin requests a sequel

1937–49 Works on the sequel to The Hobbit. On publication between 1954 and 1956, The Lord of the Rings becomes one of the biggest-selling works of fiction of all time

1945 Becomes Merton Professor of English Language and Literature

1959 Retires from Oxford University

1971 Edith Tolkien dies

1973 Dies in Bournemouth and is buried with Edith at Wolvercote Cemetery, Oxford

-

Five homes with their own orchards that will be the apple of your eye (almost literally)

Five homes with their own orchards that will be the apple of your eye (almost literally)If you've been looking enviously this year at neighbours with apple trees that have been heaving with fruit, here is the solution: five lovely homes for sale that come with their own orchards.

-

Where in the world is this? — and other pressing questions. It's the Country Life Quiz of the Day, October 14, 2025

Where in the world is this? — and other pressing questions. It's the Country Life Quiz of the Day, October 14, 2025Test your general knowledge in Tuesday's quiz.

-

How to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen

How to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen2025 marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen's birth. Here are exhibitions, events and more — happening across the UK — that mark the occasion.

-

Unputdownable: 12 page turners to see you through the rest of the winter

Unputdownable: 12 page turners to see you through the rest of the winterFrom cookbooks to cricket, biographies to Sunday Times bestsellers, Country Life contributors name some of their favourite books from last year.

-

Thomas Hardy's Wessex vs the real-life Dorset: Which bits are real, which dreams, and which are exact to the last stream and stile

Thomas Hardy's Wessex vs the real-life Dorset: Which bits are real, which dreams, and which are exact to the last stream and stileThomas Hardy’s depictions of a fictional Wessex and his own dear Dorset are more accurate than they may at first appear, says Susan Owens.

-

The English villages that are hotbeds of murder, intrigue and endless summer days — at least in the minds of novelists

The English villages that are hotbeds of murder, intrigue and endless summer days — at least in the minds of novelistsComforting yet complex, intriguing and alluring, the village setting is territory to which writers — and readers — will return again and again. Flora Watkins looks at how the customs, characters and communities of the English village have long sparked literary inspiration, from Jane Austen to Midsomer Murders.

-

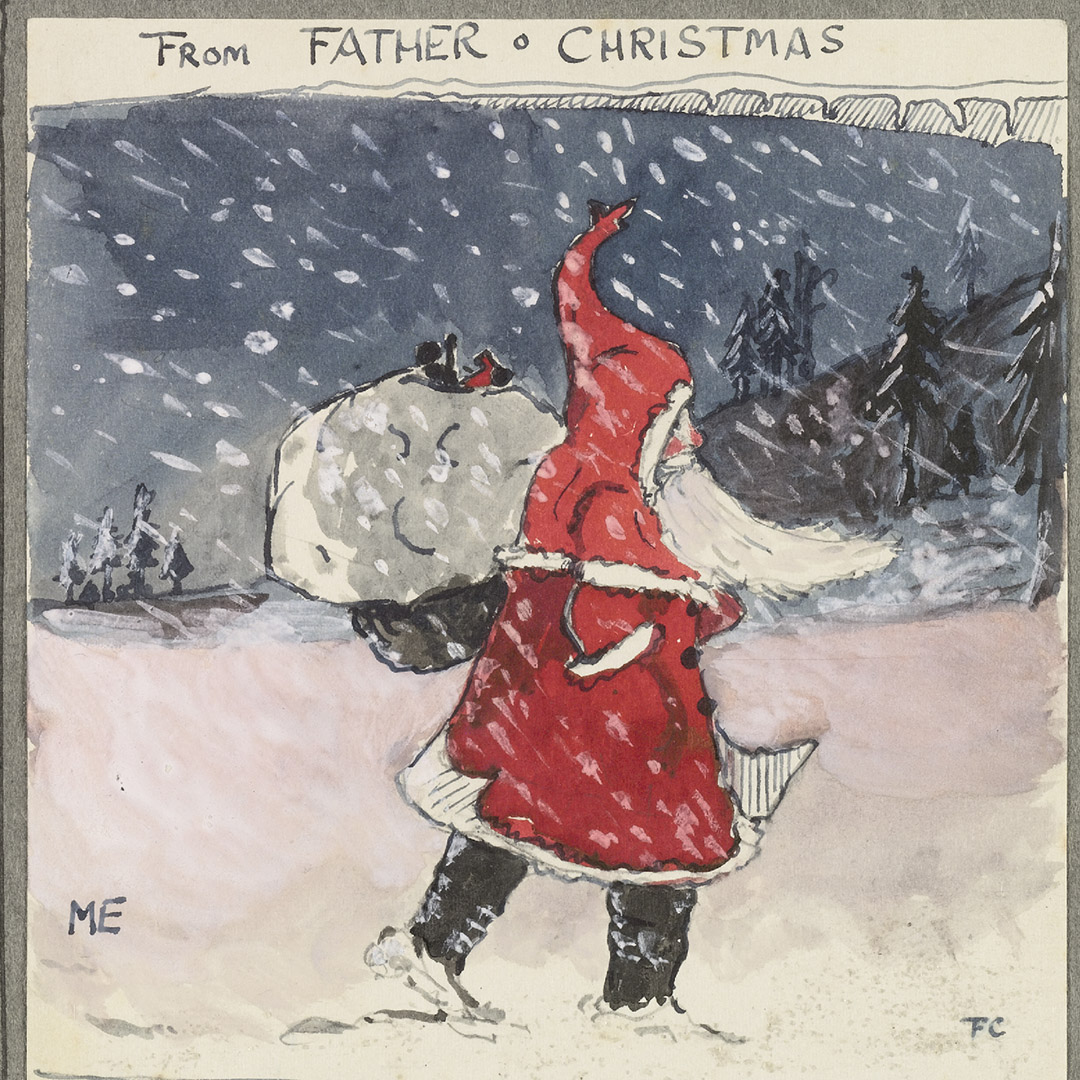

With love from Father Christmas: J.R.R. Tolkien's enchanting Christmas letters to his children

With love from Father Christmas: J.R.R. Tolkien's enchanting Christmas letters to his childrenFor nearly a quarter of a century, J. R. R. Tolkien sent his children elaborate letters and pictures from the North Pole. Ben Lerwill explores the penmanship, kindness and magic that went into Letters From Father Christmas.

-

The best characters created Charles Dickens, still utterly unforgettable even 150 years after his death

The best characters created Charles Dickens, still utterly unforgettable even 150 years after his deathCharles Dickens died 150 years ago, on 9 June 1870. Since then, Mr Micawber has become a byword for optimism, Scrooge for meanness and Uriah Heep for obsequiousness, and we still quote Mr Bumble’s ‘the law is an ass’. Rupert Godsal explains why these characters are so exuberantly unforgettable.

-

Charles Dickens timeline: The best of times, the worst of times

Charles Dickens timeline: The best of times, the worst of timesRupert Godsal paints the major events in the life and times of Charles Dickens, who died 150 years ago on 9 June, 1870.

-

In Focus: The greatest books ever written about theatre, as chosen by Michael Billington

In Focus: The greatest books ever written about theatre, as chosen by Michael BillingtonMichael Billington has been the theatre critic for Country Life (and several other publications) for decades. With theatres closed, he's turned his hand to picking out his 10 favourite books about theatrical life.