In Focus: The cello's incredible range, 'the whole way from bass to soprano, very rich and mellow', set to star at the Proms 2021

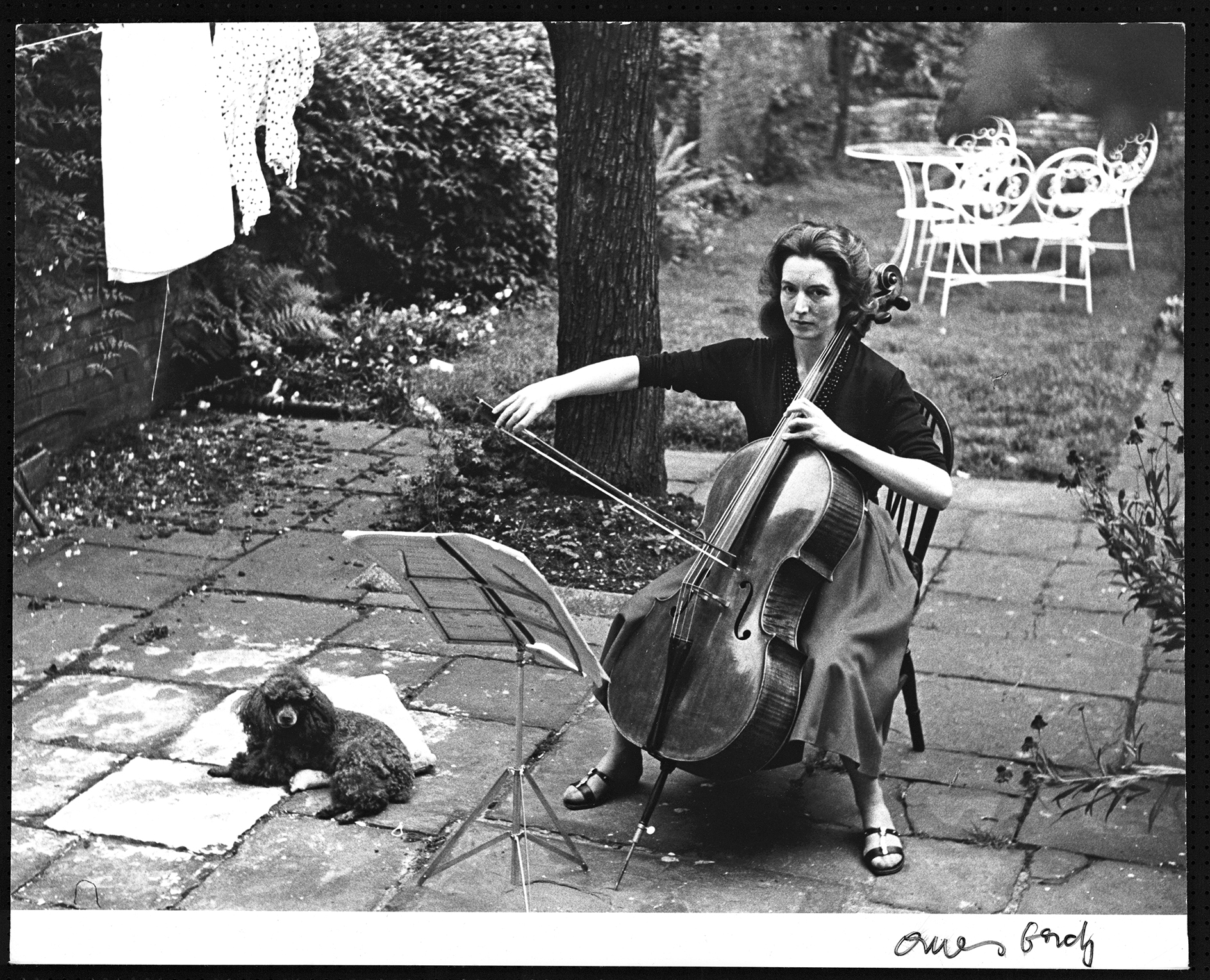

The four great cello concertos will feature in the same Proms season for the first time in history. Pippa Cuckson discovers why this mellow instrument evokes such emotion.

This year’s BBC Proms provide an unexpected feast of cello music. It is the first time in 126 years that the four warhorses of the concerto repertoire — Elgar, Dvořák, Saint-Saëns and Walton — have all been played in the same season, although, says Proms director David Pickard, the programming owes more to pandemic-related pragmatism than design.

‘These concertos seem to fit for the times we are in, because of the emotional languages they speak, but also the practicalities of social distancing,’ David explains. ‘The repertoire this year is dictated by the number of players on stage and it so happens all these concertos have manageable orchestral forces.

‘They are being performed by astonishing cellists from home and abroad,’ he adds. ‘We tend to think of the Elgar as quintessentially English and connected to Jacqueline du Pré, so to have it reflected back to us by someone who is German [Johannes Moser] will add another dimension.’

This happy accident of planning showcases the sheer range of this most beloved of stringed instruments and the fascinating links between current virtuosi and some of the past greats, whose memory is inevitably eclipsed by du Pré, Rostropovich and Tortelier.

The ‘happening’ young cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason tackles the Dvořák concerto. This Czech masterpiece has been performed 35 times at the Proms, although never more famously than in 1968 by Mstislav Rostropovich. By chance, it was the day after Soviet tanks rolled into Prague. The Russian orchestra was booed, although not ‘Slava’, who was in tears throughout. At the end, he held the score aloft, as if to show where his sympathies lay.

Comparisons are inevitable and there is keen interest in what magic Mr Kanneh-Mason can conjure from the 1700 Matteo Gofriller cello bought for him for last month by private investors. He says it has ‘an uncanny capacity to respond to — almost to anticipate — my style of playing’. There is a notion that stringed instruments absorb the character of previous players, although some find this fanciful.

Argentine virtuoso Sol Gabetta has two historic cellos on loan, most recently the Stradivarius played by Guilhermina Suggia, a celebrated inter-war figure who was the long-term muse of Pablo Casals and was painted by Augustus John. ‘I feel really honoured to play these instruments, but it is also a huge responsibility,’ says Miss Gabetta. ‘They teach me every day what they want and do not want. If a cello is not challenged enough it will lose some of its colours. It’s like a partner and you need to know it very well to get the best out of it. I usually need about three years!’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

She plays the Saint-Saëns A minor Concerto, which was last performed at the Proms by Steven Isserlis in 2007 and then not since the First Night in 1964, by Amaryllis Fleming. (To square that circle, Miss Fleming then learned in later life that she was John’s biological daughter.)

Miss Gabetta feels that the Saint-Saëns, which opens with a startling cascade down the fingerboard, has unfairly dropped off the concert promoter’s radar. ‘You often study it at a conservatory and afterwards it is forgotten. It’s perhaps a bit short [19 minutes], but the clear structure makes it impossible for the soloist to hide — every note counts,’ she observes. ‘The phrasing and the meaning of the bel canto is probably at its peak in this repertoire.’

The goal of playing any instrument is artistic expression, but it has to be said that the cello’s initial attraction can be plain visceral, sometimes the butt of racy observation. Amaryllis Fleming was the half-sister of Ian Fleming and, in his short story The Living Daylights, James Bond muses about the incongruity of female cellists, concluding: ‘They should invent a way for women to play the damned thing side-saddle.’

‘Yes, it is a very physical instrument to look at,’ agrees Jesper Svedberg, the BSO’s principal cellist. ‘It’s big and stretchy and it takes a lot of power to play it. You only have to think of how du Pré went up and down it with all that flamboyancy.

‘Then there is the register, very close to the human voice, covering the whole way from bass to soprano. It’s very rich and mellow, yet can also be the singing voice. In the Elgar concerto, much of the register used is quite high, so you get that effect of soaring over the rest of the orchestra, and listeners find that so exciting. And in the romantic repertoire, the cellos get a lot of the melodies. That makes it very rewarding to play, regardless of what the soloist is doing.’

Mr Isserlis is less convinced about personality transfer to an instrument, especially, as he jokes, ‘as a French aristocrat owned mine and he ended up on the guillotine!’ He used to play the De Munck-Feuermann Stradivarius, named after two other distinguished former players. The Royal Academy of Music now loans him the Marquis de Corberon Stradivarius formerly played by Zara Nelsova, whom Mr Isserlis met many times as a student.

‘It’s more a case of certain personalities being attracted to certain instruments,’ says Mr Isserlis. ‘I have set up this cello differently. Zara had it quite “tight”, whereas I use older-type strings, quite relaxed, to enhance the poetry of the sound. I’ve played the two Strads side by side and they are utterly different, although their souls are strongly there.’

Nelsova studied with Feuermann and Casals and was dubbed ‘Queen of the Cello’ in the 1950s. She gave the London premieres of works by Hindemith, Bloch and Shostakovich and was the pre-eminent Elgar interpreter until du Pré.

Nelsova also championed the Walton concerto under the composer’s baton. This less familiar masterpiece will be performed by Mr Isserlis at his 15th Proms appearance: ‘Walton himself thought his cello concerto was his best. He slaved away over it and was incredibly insecure. To me, it’s one of the most beautiful pieces ever written, strong and dramatic.’

It is the personal favourite of the Proms director, too. ‘I fell in love with the Walton when I was 12,’ reveals Mr Pickard. ‘It has such immediacy and energy. To have a world-class cellist playing something we don’t hear that often is what the Proms is all about.’

The BBC Proms runs until September 11 — www.bbc.co.uk/proms. Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto in A Minor with Sol Gabetta on August 2; Elgar Cello Concerto with Johannes Moser on August 9; Walton’s Cello Concerto with Stephen Isserlis on August 12; Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor with Sheku Kanneh-Mason on September 5.

In Focus: Music in a time of Covid-19, from drive-in operas to the 'Spotify of classical'

Classical music has been hit hard by coronavirus, but there are all manner of ways for musicians and music lovers

In Focus: How the violin virtuoso Nicola Benedetti is changing the way we teach music

The violinist Nicola Benedetti speaks to Claire Jackson about virtual teaching, playing Elgar and lobbying the government.

In Focus: The trench cello which brought the joy of music to the First World War

The men who spent years in the trenches of France and Belgium found all manner of ways to bring a

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagne

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagneAn upwardly mobile spaghetti Bolognese, lasagne al forno, with oozing béchamel and layered meaty magnificence, is a bona fide comfort classic, declares Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025Thursday's Quiz of the Day asks exactly how popular Baywatch became.

By Toby Keel