In Focus: How the violin virtuoso Nicola Benedetti is changing the way we teach music

The violinist Nicola Benedetti speaks to Claire Jackson about virtual teaching, playing Elgar and lobbying the government.

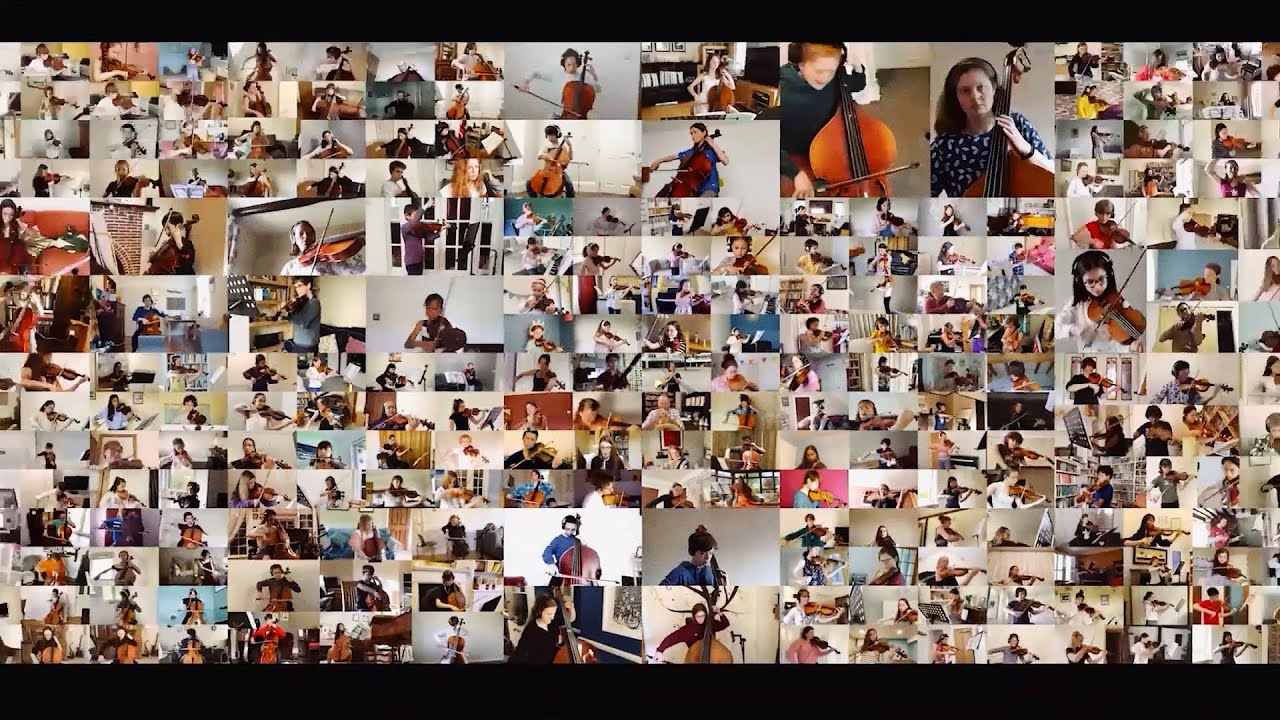

A patchwork of string players waves and smiles at the camera. The participants, aged two to 92, are dotted across the world, from Scotland to Siberia. A cat peers over a music stand as one young musician wrestles with a tricky phrase, trying to emulate the posture demonstrated by the violinist on his phone.

His music teacher is international soloist and educator Nicola Benedetti. Students are not using YouTube videos — Miss Benedetti is there, on the screen in real time, talking directly to 7,159 participants from 66 countries as part of the Virtual Benedetti Sessions.

The sessions were not intended to be delivered this way. The series is part of a project launched by the Benedetti Foundation, which has already hosted large-scale, in-person workshops in Glasgow, London and Dundee. The foundation’s strapline is ‘unite, inspire, educate’ and the lessons are open to musicians at every level.

‘We were about to head to Northern Ireland for the next leg. When we realised that wasn’t possible, we launched the virtual sessions,’ explains Miss Benedetti. ‘We’ve been overwhelmed at the response. I’d even claim that the project has prevented a number of people from giving up their instruments. It’s very gratifying.’

The Virtual Benedetti Sessions culminated in a concert like no other. Miss Benedetti presented virtual ensemble performances, which combined pre-recorded videos and a clock to count in viewers playing along at home. Thanks to latent internet speeds, it’s impractical to play live music in a group without some pre-recorded anchor points. One highlight was a special version of Paganini’s Caprice No 24 (re-worked for 12 solo violins) with violin luminaries, including Alina Ibragimova, ‘passing’ the melodies across the screen.

It’s difficult to believe that the foundation is still a fledgling organisation. It was registered as a charity in September 2019, the same year that Miss Benedetti, who turned 33 last month, was appointed a CBE, following her receipt of the Queen’s Medal for Music (2017) and an MBE in 2013.

‘It’s crazy to think how many workshops we’ve done in that time,’ she says. ‘We receive no Government funding — our work is possible through individual donations and the generosity of our chairman. Fundamentally, we try to put an injection of energy into music education, prioritising parts that can often be left behind: the creativity and story-telling in particular.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

As teachers begin the unenviable task of catching up with learning that might have been missed during school closures, there is a real risk that music will be pushed even further down the pecking order. Miss Benedetti’s attempts to reignite interest in music education, especially stringed instruments, recalls that of another great violinist and educator, the late Yehudi Menuhin. The connections are perhaps unsurprising. Ayrshire-born Miss Benedetti studied at Surrey’s prestigious Yehudi Menuhin School under Baron Menuhin himself.

As well as her educational work (she’s president of the European String Teachers Association (UK) and supports the National Youth Orchestra Young Ambassadors scheme), the violinist is frequently drafted in to advocate for music more broadly. A few days before our interview, Oliver Dowden, Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, summoned Miss Benedetti, the trumpeter Alison Balsom, cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason and conductor Sir Simon Rattle at short notice to thrash out ways the classical-music community can move forward despite the current social-distancing restrictions.

The quartet released a statement concluding: ‘We are poised and ready for collaboration, to urgently save our industry and thousands and thousands of jobs — but also to help lift people out of this awful situation.’ The Prime Minister subsequently pledged a £1.5 billion rescue package for the Arts.

Next month, Miss Benedetti releases a new recording of the Elgar Violin Concerto, performed with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Vladimir Jurowski. Elgar’s music, having fallen from favour during the late 20th century, is enjoying a renaissance. ‘I would like to think that there is an increased appreciation of that open-hearted Romanticism you can hear in the concerto,’ she considers. ‘Fashions change in music, as elsewhere. We may be seeing a reoccurrence of a need for emotional complexity.’

Earlier this year, Miss Benedetti received her first-ever Grammy for her recording of the Wynton Marsalis Violin Concerto with the Philadelphia Orchestra and conductor Cristian Macelaru. Her next album will be ‘more conceptual’, she says. ‘I’m looking into the social history surrounding the violin itself.’

Her own violin was made by Antonio Stradivari in 1717, one of about 500 Stradivariuses left in the world. ‘It belongs to Jonathan Moulds, who kindly allows me to play it,’ she notes. ‘Having a long-term relationship with an instrument of such prestige is an enormous privilege.’

We will be able to hear that glorious instrument in concert again very soon. Miss Benedetti joins Miss Ibragimova and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment for a special live-streamed Prom this September (date to be confirmed). As her online videos feature animated red curtains drawing across an imaginary stage, the violinist is counting the days until she can play on a real one. ‘This period has been incredibly disorientating,’ she says, ‘I cannot wait to return to the Royal Albert Hall.’

In Focus: The Mansions of Cornwall, as they existed in 1846

A rare survey of over 80 Cornish country houses has been found and reprinted – Adrian Tinniswood takes a look.

In Focus: Henry and John Crealock, the Victorian military brothers who turned their hands to art

Huon Mallalieu considers the careers of Henry Hope Crealock and John North Crealock, the Victorian army officers and sometime-artists whose

Credit: David Milne, Tent in Temagami, 1929, Collection of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound, Ontario, bequest from the Douglas M. Duncan Collection, 1970. © The Estate of David Milne

In Focus: The Canadian hermit's work that is a dystopian alternative to Monet

Canadian artist David Milne moved from city to country, eventually ending up as a hermit in a remote part of

In Focus: The Rembrandt portrayal of Christ which contains the fingerprints of the great master himself

A wonderful Rembrandt that went under the hammer recently contains a fascinating imprint of its creator, as Huon Mallalieu reports.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

The big reveal: A first look at Country Life's RHS Chelsea Flower Show stand

The big reveal: A first look at Country Life's RHS Chelsea Flower Show standInterior designer Isabella Worsley reveals her plans for Country Life’s ‘outdoor drawing room’ at this year’s RHS Chelsea Flower Show.

By Country Life

-

Schreiber House, 'the most significant London townhouse of the second half of the 20th century', is up for sale

Schreiber House, 'the most significant London townhouse of the second half of the 20th century', is up for saleThe five-bedroom Modernist masterpiece sits on the edge of Hampstead Heath.

By Lotte Brundle