Curious Questions: Why is the pantomime dame always played by a man?

Every year, millions of people across Britain will chuckle their way through a pantomime featuring a man playing the main female role, and usually a girl playing the lead male role. How it came to be so is a fascinating tale.

Let's blame it on the weather – and the lack of light at this time of year. The dark winters of the frozen north have long been broken by feasts of light and cheer. For the Romans, lamenting the loss of Mediterranean sunshine, the festival of Saturnalia was life-affirming. In a reversal of the natural order, men became women, old became young, slave became master.

The idea endured past the Dark Ages, with medieval and Tudor aristocratic households whipped up into a fever of festive chaos by a Lord of Misrule. Henry VIII enjoyed Misrule, but banned the concurrent practice of Boy Bishops in 1542, believing that it damaged the dignity of the church – presumably he was keen to retain what little remained following the stripping of churches and the dissolution of the monasteries a few years previously. Today, however, the tradition has been revived, with Girl Bishops being allowed, too, a development that would probably have been considered even more topsy-turvy in Tudor times.

The link between such shenanigans and the pantomime dame tradition that emerged in the 19th century is closer than it might first appear. Cross-dressing had been part of the theatrical tradition since its earliest days, but it’s this seasonal subversion of the normal order that lies at the heart of the creation of Widow Twankey et al.

Female actresses, though banned in Shakespeare’s day, had returned to the British stage long before panto became popular. It was in the 1660s, in fact, when Margaret Hughes became England’s first professional actress, and male actors were (for a while) even banned from playing female roles. It was the same on the Continent: in Spain, for example, cross-dressing had been a staple age of the comedia of Golden Age theatre, but in the 17th century laws were passed which, for a while, prohibited women dressing as men on stage.

By the early 19th century, however, such concerns had relaxed – and British pantomime, derived from Italian commedia dell'arte, was the beneficiary. At the time traditional folk stories were replacing classical sketches as the basis of panto, and the cross-dressing of the commedia evolved into a key part of the fun. Thus it was that the tradition emerged of a principal boy played by a young woman, and a co-starring dame played by an old man. It might be predictable and obvious, but it’s also subversive, amusing and incredibly enduring.

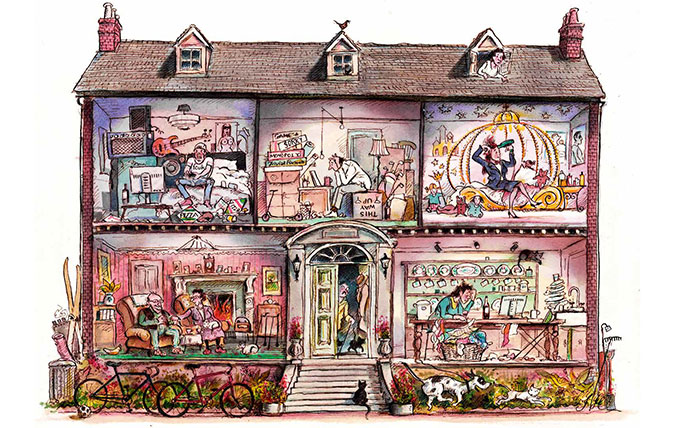

This format was probably set in stone by the clown Grimaldi – the A-list superstar of his day – who first immortalised the role of the Baroness in an 1820 staging of Cinderella. The first buxom, booming Widow Twankey of Aladdin was invented by a distant cousin of the elegant Lord Byron, the playwright H. J. Byron, who also created Buttons and cast men as the Ugly Sisters. He named the Widow in his 1861 production, after a tea popular at the time; ‘she’ was played by James Rogers. Today, it’s a tradition that is as popular as ever.

Why we still love pantomime ('Oh no we don't'...'Oh yes we do'...)

Corny, hammed-up, ritualistic – and yet Pantomime is still a hugely lovely theatrical format. Perennial pantomime villain Kit Hesketh-Harvey explains

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Credit: Country Life

Six ways to stop your children moving back home – and what to do if they come anyway

Kit Hesketh-Harvey explains why the 'boomerang generation' keep on coming back - and how to stop 'em.

Credit: Alamy

In defence of round-robin letters: Boastful, delusional, unintentionally hilarious

The smugness and often staggering insensitivity of the Christmas round-robin letter is enough to drive one to drink, but Kit

Octavia, Country Life's Chief Sub Editor, began her career aged six when she corrected the grammar on a fish-and-chip sign at a country fair. With a degree in History of Art and English from St Andrews University, she ventured to London with trepidation, but swiftly found her spiritual home at Country Life. She ran away to San Francisco in California in 2013, but returned in 2018 and has settled in West Sussex with her miniature poodle Tiffin. Octavia also writes for The Field and Horse & Hound and is never happier than on a horse behind hounds.

-

This Suffolk home is a perfect escape from the world and it comes with its own stretch of river and 20 acres

This Suffolk home is a perfect escape from the world and it comes with its own stretch of river and 20 acresThis idyllic home in Suffolk is the perfect village home.

-

We remember Prunella Scales in the Country Life Quiz of the Day, October 28, 2025

We remember Prunella Scales in the Country Life Quiz of the Day, October 28, 2025The actor passed away today and is best known for her role opposite John Cleese in the TV programme 'Fawlty Towers'.