Curious Questions: Why is an artist's final performance called their 'swansong'?

Martin Fone, author of 50 Curious Questions, investigates.

Some artists find it hard to call it a day. Elton John is embarking upon a 300-concert world tour to mark his retirement from touring. It will span three years.

Dame Nellie Melba spent eight years, between 1920 and 1928, performing what she called final concerts, prompting the Australians, famed for their inventive use of language, to spawn the phrase 'more farewells than Nellie Melba'. Frank Sinatra caught the same bug, performing more farewell tours than you could shake a stick at.

But it's Neil Young who summed it up best (as is often the case) in an interview with the Rolling Stone magazine in March 2018: 'When I retire, people will know, because I’ll be dead.'

As a child I was fascinated by the fables attributed to Aesop. In The Swan and the Goose, the cook goes to the outhouse in the dark to get the goose to put in the pot. He picks the swan by mistake and it is only saved when it bursts into song, an early reference to the propensity of a swan to sing just before its demise. Given the uncertainty surrounding the dating of these fables, it may not be the earliest.

There are references to the volume of a swan’s call in Hesiod and the clarity, sonority and sweetness of its song in Alcman and Pindar, but it was Aeschylus, in his play Agamemnon (dated to 458BC) who gave us the image of a swan bursting into song just before its death. Clytemnestra describes Cassandra’s death throes as 'singing her last death-laden lament like a swan.'

By the 3rd century BCE, the notion that a swan sings a mournful song immediately before its death had attained proverbial status. But is there any truth to it?

Pliny the Elder, in his Naturalis Historia from around 77 CE, was emphatic in his refutation: 'observation shows that the story that the dying swan sings is false.' Yet while it is true that swans are not noted for their vocal abilities – there is the Mute Swan, after all – they do indeed make noises.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Whooper Swan, which was to be found in Ancient Greece, makes a honking sound, hence its name, and when it dies, because it has an extra tracheal loop in its sternum, its collapsing lungs make a long, drawn-out series of notes. Beautiful it may not be – the Encyclopaedia Britannica describing it in 1823 as akin to 'a clarionet when blown by a novice in music' – but a sound it certainly is. It was enough to convince the Prussian naturalist, Peter Pallas, towards the end of the 18th century, that this was the origin of story.

Swans here in Britain are protected so I cannot vouch for the veracity of the story from personal experience. I will have to rely on the testimony of a zoologist, D G Elliot, who winged a tundra swan in flight and noted, in 1898, that as it made its long glide down towards terra firma, it gave out a series of 'plaintive and musical' notes which sounded 'like the soft running of the notes of an octave.'

However loose the association between a swan’s song and its death is in reality, you can’t keep a beautiful image down. Writers down the ages, perhaps more influenced by Aesop and Aeschylus than the killjoy Pliny, have been drawn to it. Chaucer, in his Parlement of Foules, wrote of the jealous swan singing before his death and Portia in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice says, 'then, if he loses, he makes a swan-like end, fading in music.' Even Leonardo da Vinci repeated the canard, writing that, 'the swan … sings sweetly as it dies, that song ending its life.'

Turning to swansong used specifically as a noun, the Scottish evangelical cleric John Willison referred to King David’s 'swan-song'in his Scripture Songs, written in the middle of the 18th century: in the second of his Five Sacramental Sermons, he wrote, 'you may sing that swan-song.'

The phrase was sufficiently well-known for Samuel Taylor Coleridge to use in his epigram On a Volunteer Singer, to make a joke – a joke that I'll be sure to remember next time I’m made to suffer through a karaoke session:

Swans sing before they die; ‘twere no bad thing Did certain persons die before they sing.

The specific association of a musician with a swansong can probably be traced back to Franz Schubert. He died tragically young in 1828 at the age of 31, officially from typhoid but more likely syphilis. A year later, Tobias Haslinger published a collection of songs which Schubert had written just before his death, under the title of Schwanengesang. This was the composer’s farewell to the world.

Whether they know it or not, artists who perform their swan-song are stepping into Schubert’s shoes. As he was only 5'1" and was nicknamed Schwammerl – ‘little mushroom’ – those shoes are unlikely to have been that big...

Martin Fone is the author of 50 Curious Questions, available via Amazon.

Credit: Alamy

Curious questions: Are you really never more than six feet away from a rat?

It's an oft-repeated truisim about rats, but is there any truth in it? Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions',

Credit: Jamon Iberico

Curious Questions: Do delicious hams from little acorns grow?

Jamón Iberico is undeniably delicious – and undeniably pricey. Martin Fone took a trip to Spain to find out how it

Credit: apples and oranges Photo by Best Shot Factory/REX/Shutterstock

Curious Questions: Can you actually compare apples and oranges?

It's repeated so often these days that we've come to regard it as a truism, but are apples and oranges

Curious Questions: Do you get wetter running or walking in the rain?

Does running in the rain get you out of it quicker? Or do you just run into more water more

Credit: Corbis via Getty Images

Curious Questions: What is the biggest potato ever grown?

As harvests come in across Britain, we always enjoy pictures of giant vegetables appearing at various shows. But the tale

Toby Keel is Country Life's Digital Director, and has been running the website and social media channels since 2016. A former sports journalist, he writes about property, cars, lifestyle, travel, nature.

-

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagne

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagneAn upwardly mobile spaghetti Bolognese, lasagne al forno, with oozing béchamel and layered meaty magnificence, is a bona fide comfort classic, declares Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025Thursday's Quiz of the Day asks exactly how popular Baywatch became.

By Toby Keel

-

Curious Questions: Why do golf balls have dimples? And why are tennis balls furry?

Curious Questions: Why do golf balls have dimples? And why are tennis balls furry?As the weather picks up, millions of us start thinking about dusting off our golf clubs and tennis rackets. And as he did so, Martin Fone got thinking: why aren't the balls we use for tennis and golf perfectly smooth?

By Martin Fone

-

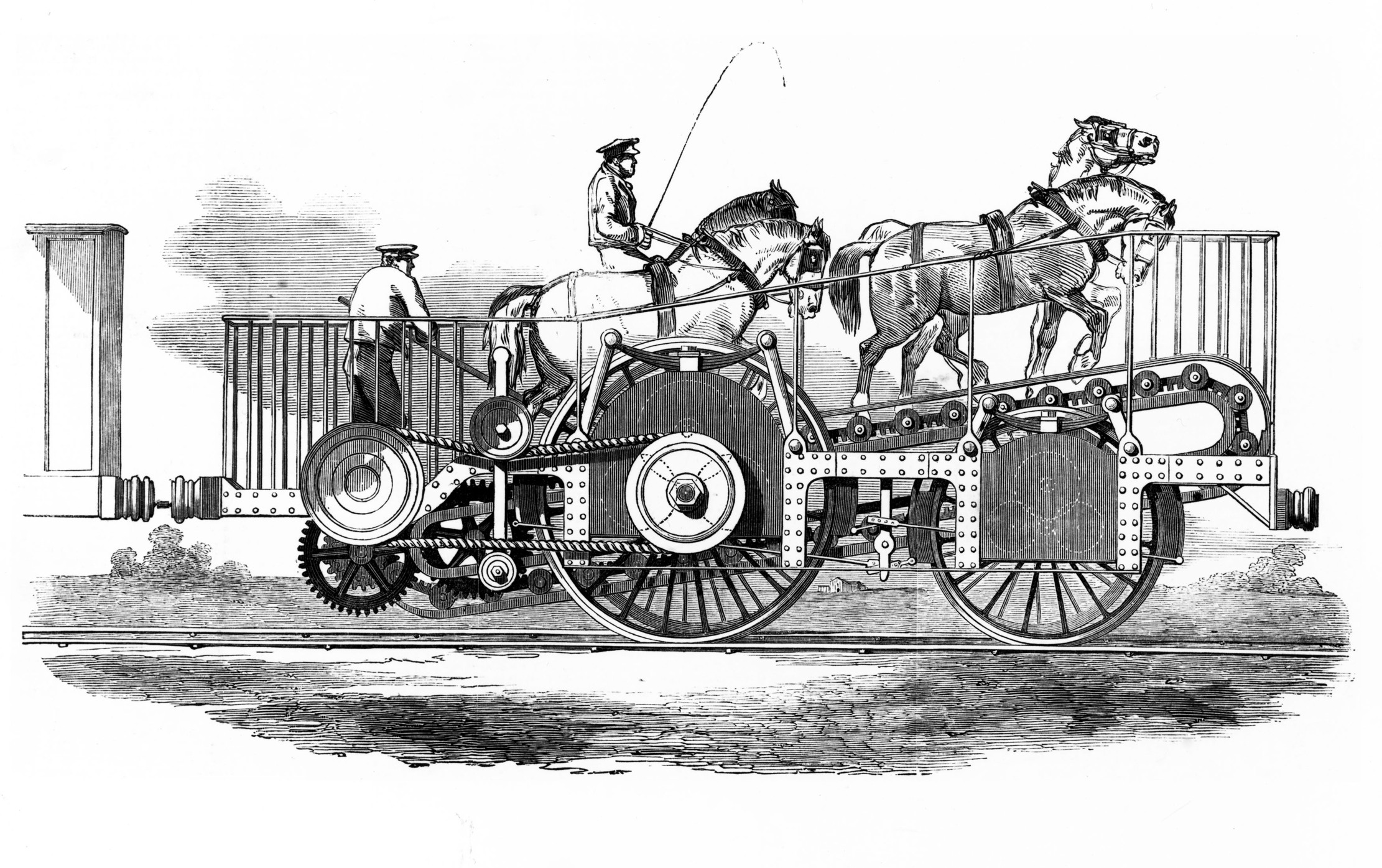

Curious questions: How a horse on a treadmill almost defeated a steam locomotive

Curious questions: How a horse on a treadmill almost defeated a steam locomotiveThe wonderful tale of Thomas Brandreth's Cycloped and the first steam-powered railway.

By Martin Fone

-

You've got peemail: Why dogs sniff each other's urine

You've got peemail: Why dogs sniff each other's urineEver wondered why your dog is so fond of sniffing another’s pee? 'The urine is the carrier service, the equivalent of Outlook or Gmail,' explains Laura Parker.

By Laura Parker

-

Curious Questions: Which person has spent the most time on TV?

Curious Questions: Which person has spent the most time on TV?Is it Elvis? Is it Queen Elizabeth II? Is it Gary Lineker? No, it's an eight-year-old girl called Carole and a terrifying clown. Here is the history of the BBC's Test Card F.

By Rob Crossan

-

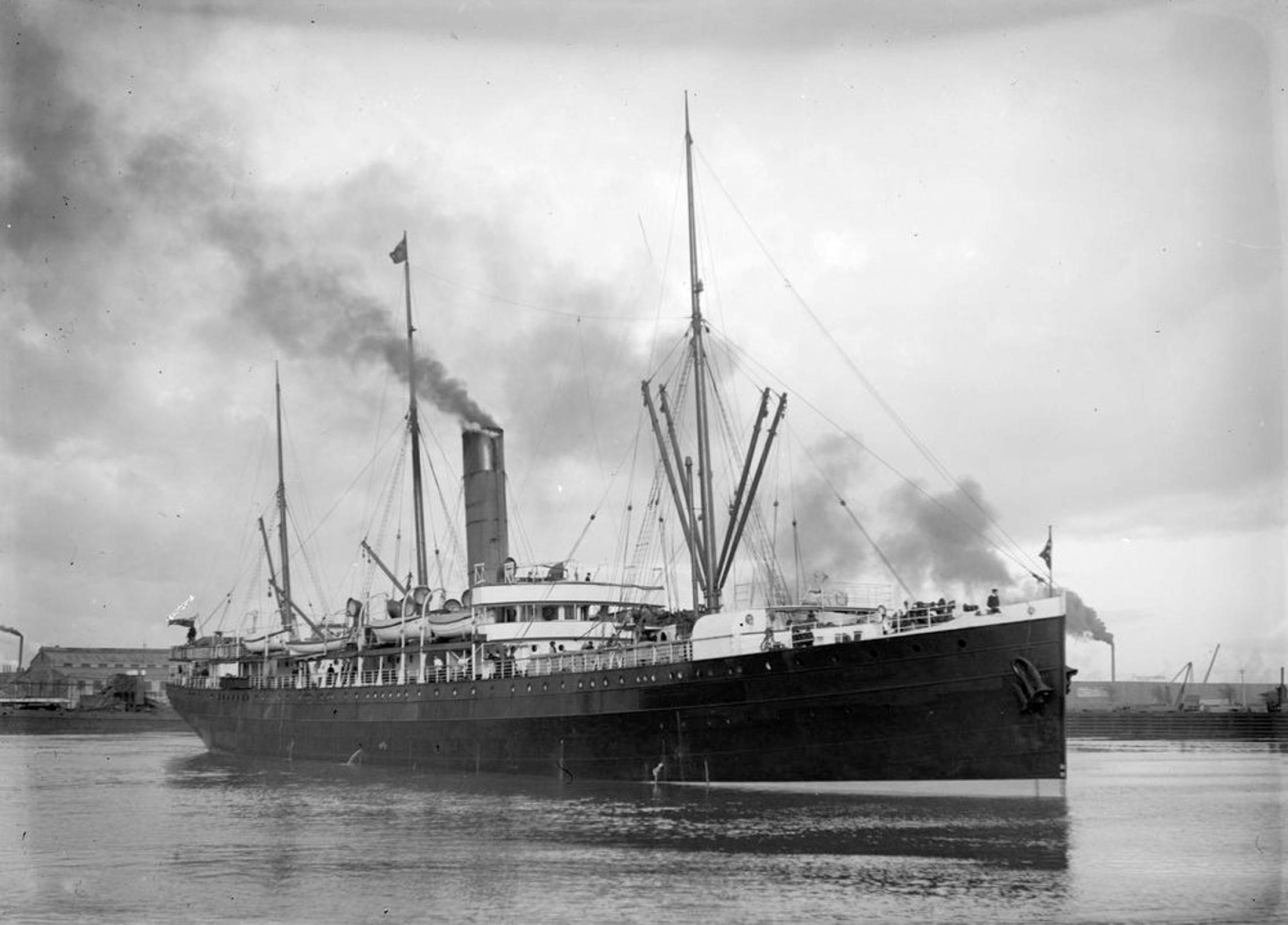

The ship that was in two different centuries, two different years, two different months, two different days and two different seasons, all at the same time

The ship that was in two different centuries, two different years, two different months, two different days and two different seasons, all at the same timeOn December 31, 1899, the SS Warrimoo may have travelled through time — but did it really happen?

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Was music's famous 'Lady of the Nightingales' nothing more than a hoaxer?

Curious Questions: Was music's famous 'Lady of the Nightingales' nothing more than a hoaxer?Beatrice Harrison, aka ‘The Lady of the Nightingales’, charmed King and country with her garden duets alongside the nightingales singing in a Surrey garden. One hundred years later, Julian Lloyd Webber examines whether her performances were fact or fiction.

By Julian Lloyd Webber

-

Curious Questions: Who wrote the Happy Birthday song?

Curious Questions: Who wrote the Happy Birthday song?There are few things less pleasurable than a tuneless public rendition of Happy Birthday To You, says Rob Crossan, a century after the little ditty came into being

By Rob Crossan

-

Why do we get so many April showers?

Why do we get so many April showers?It's the time of year when a torrential downpour can come and go in minutes — or drench one side of the street while leaving the other side dry. It's all to the good for growing, says Lia Leendertz as she takes a look at the weather of April.

By Lia Leendertz