Chris Barber: Britain’s Godfather of Jazz playing off key, and the day he entertained 1m people

Chris Barber, Britain's Godfather of Jazz, has been a leading light of this country's jazz scene for over half a century. He talks to Jack Watkins.

Reading the early pages of Chris Barber’s autobiography, Jazz Me Blues, it’s easy to get sidetracked by his connections.

His father Donald, taught by John Maynard Keynes at Cambridge, was a distinguished economist who turned down Clement Atlee’s offer of a safe seat that would have led to a job as Chancellor. His mother, Hettie, was the first Socialist mayor of Canterbury.

At St Paul’s School, Mr Barber was a classmate of Stanley Sadie, the musicologist who edited the first edition of The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Barber also chose the musical path, carving out a career that eclipsed them all.

This year is the centenary of the release of the first jazz records, by the New Orleans-based Original Dixieland Jazz Band. As most anniversaries are milked for maximum commercial yield in the 21st century, it’s surprising more of a fuss isn’t being made of it.

The 10-piece Big Chris Barber Band is doing its bit, however, with performances the length and breadth of Britain, including at Cadogan Hall, London SW1, on September 18: the material is a range of jazz or jazz-related styles, including New Orleans, ragtime and the blues, to the more complex arrangements of Duke Ellington and Modern Jazz.

'Improvising is part of the music, but you’re still meant to play proper notes... They thought that playing jazz meant playing off-key.'

You could hardly experience all this in better company. Mr Barber, who is now 87, has achieved true eminence as a trombone-playing bandleader and his commitment to raising standards among European musicians is as firm as it was in his earliest public concerts more than 65 years ago.

‘There are lots of young musicians who want to play jazz today, but not all succeed in doing it terribly well,’ points out the affable Mr Barber.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘The presentation doesn’t always have a lot of feeling behind it. We don’t try and sell our music as teaching people, but we do like to show we’re trying to play it in the right way and l like to tell people a little of the background to what they’re hearing, without going too deep.’

When Mr Barber first started out, standards were very low indeed. ‘You’d read a review about how good someone was, but when you went to see them, it was obvious they weren’t performing to a technically high level.

‘Improvising is part of the music, but you’re still meant to play proper notes, not something half-way between an A and a B flat. They thought that playing jazz meant playing off-key.’

Jazz reached peak popularity in Britain in the 1950s, but it’s not true that it wasn’t played here before then. ‘The Original Dixieland Jazz Band came over in 1919 for the opening night of the Hammersmith Palais,’ Mr Barber reveals.

‘The floor could accommodate 3,000 dancers. Imagine the noise of 3,000 people dancing the quickstep! However, they complained the band was too loud, even though it was playing without a microphone.’

Some interwar dance bands incorporated ‘hot’ numbers, such as Chinatown, and the popularity of the Charleston gave further room for jazz-influenced offerings. ‘There was something pretty close to jazz being played in some London nightclubs. American jazz players would work in the orchestra at places such as The Savoy. Kurt Weill’s The Threepenny Opera [1928] is set in Soho and the music is supposed to be that of a cheap, second-rate nightclub band playing bluesy stuff, so it was there, but it didn’t get wider recognition.’

Postwar, it was the enthusiasm of young British musicians like Mr Barber, Humphrey Lyttelton and Ken Colyer that catapulted traditional jazz to the forefront.

Lyttelton’s trumpet playing, inspired by the finest solo artist of them all, Louis Armstrong, convinced Mr Barber that it was something worth doing professionally. Colyer, who for a time headed Mr Barber’s band, preached that the New Orleans style of jazz, in which the front line of players improvise collectively, represented the music in its purest form.

'The night before the Coronation in 1953, we went out and marched and played in front of one million people.'

However, Mr Barber recognised that, for the music to be palatable to a wider audience, you needed to offer them a melodic hook. One of the finest examples of his work, which combined the New Orleans feel with a broader accessibility, was a version of an old song, Isle of Capri, which the band – under the name Ken Colyer’s Jazzmen – featured on its historic New Orleans to London LP in 1954. This 10in album was the first British jazz record to have a significant effect on the home market.

The Martinique, another Barber adaptation of an older piece, is a further classic worth seeking out, originally released as a 78rpm on the Decca label after Colyer’s controversial departure.

In later years, Mr Barber, a blues enthusiast, embraced other, more modern jazz forms, but he still features New Orleans marching band numbers such as Bourbon Street Parade in his shows. I sense he fears such sounds are struggling to be heard in an increasingly dense musical marketplace. He tells the story of how, in the earliest days, his band regularly performed before the cognoscenti in the basement of the Catholic Church of the Annunciation, at Bryanston Street, W1.

‘The night before the Coronation in 1953, we went out and marched and played in front of the one million people who were gathering overnight on the pavements around Marble Arch,’ he says.

‘No one noticed – we didn’t hear anyone say “Oh, did you hear that New Orleans jazz?” But there was a period, not so long ago, when they would have recognised it. Now, I think they’ve probably forgotten again. But we keep going, just doing the music as best we can, you know?’

The Big Chris Barber Band goes on tour from September 9 to December, with venues including Buxton, Harrogate, Peterborough and Basingstoke. See www.chrisbarber.net.

My favourite painting: Nicholas Cullinan

'...it perfectly captures the charisma, genius and tragedy of its subject.'

Credit: La La Land

La La Land: The apotheosis not just of Hollywood musicals, but of Hollywood music

La La Land is merely the latest, greatest example of the symbiosis between music and film which is as old

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

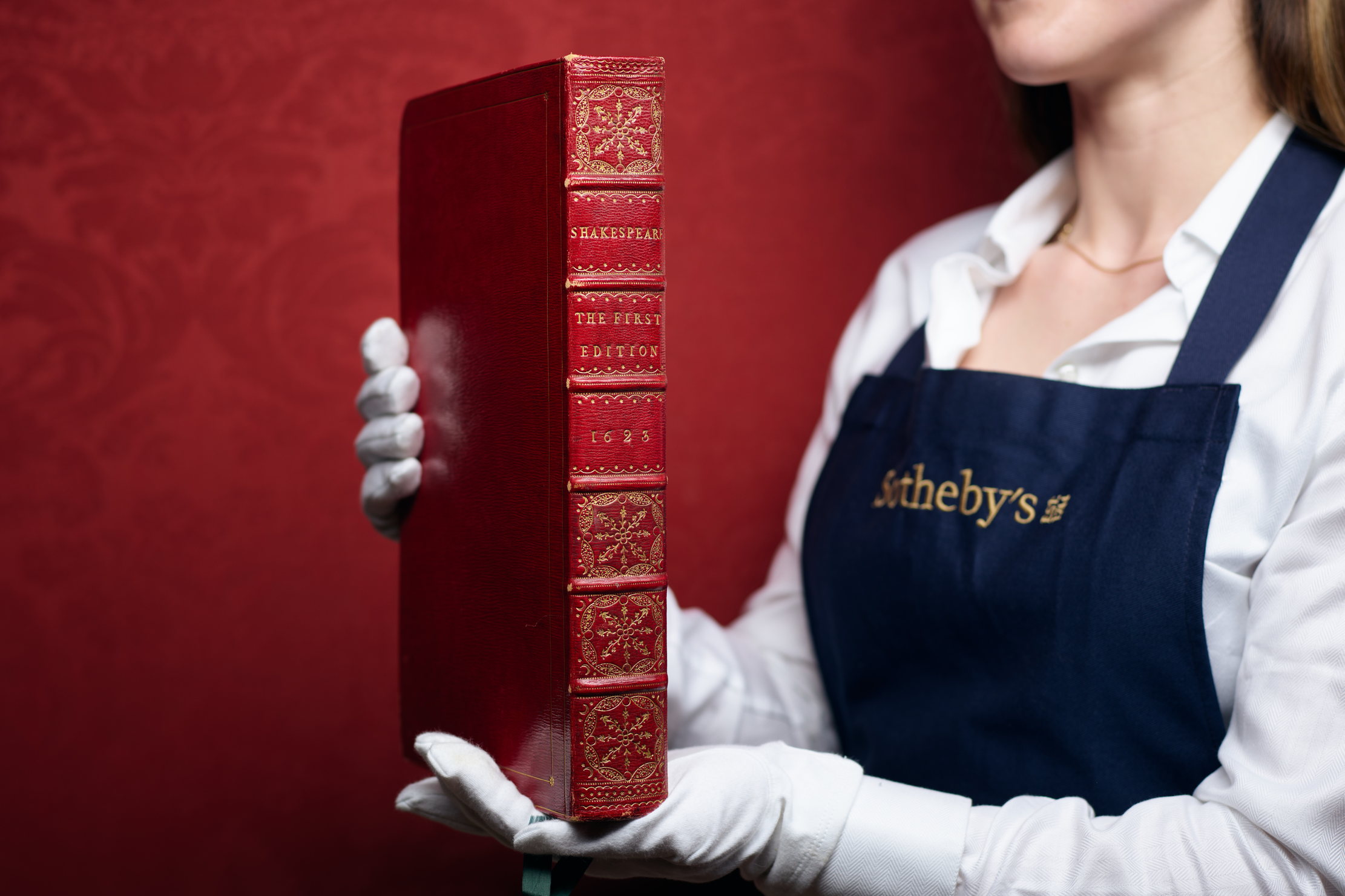

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow down

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow downThe glorious Andalusian-style villa is found within the Lomas de Marbella Club and just a short walk from the beach.

By James Fisher