Border by Kapka Kassabova: 'a moving study of the tragic borderland between Greece, Bulgaria and Turkey'

Transcending boundaries.

Border by Kapka Kassabova (Granta, £14.99)

In 2006, I crossed from Bulgaria to Greece through a brand-new frontier post, its surveillance equipment still wrapped in plastic. It marked the softening of borders as Bulgaria prepared to join the EU. The Iron Curtain’s anti-tank defences were still visible in the scrubby no-man’s land. So remote and forgotten was this corner of Thrace that, as I entered Greece, two huge dogs crossed the road and I realised they were wolves.

This stretch of border, where Bulgaria abuts Greece and Turkey, is the subject of this timely and moving book. National borders were established after the Balkan Wars and the demise of the Ottoman Empire, when millions of people were exchanged and forced to begin new lives in new territories. Soon, that border became a barricade, imprisoning not just a nation, but the entire Eastern Bloc. Now, the barricade is being re-erected against the latest migratory swathe.

The author meets individuals who tried, and mostly failed, to get out and others now trying desperately to get in. She also explores ethnically complex communities inhabiting its fringes, which were closed off for generations.

In the 1970s and 1980s, sandal-wearing East Germans chose this exit route because it was supposedly less rigorously patrolled than their own, but they were usually betrayed by Bulgarian shepherds. They spent years in gaol, if they were lucky, and were shot or beaten to death if not. One mistakenly thought he had made it to Greece and was spotted resting in a meadow peeling a celebratory apple—he died in hospital. The Bulgarian barracks commander showed off the young man’s knife as a trophy—the author meets the guilty shepherd’s son. She attempts to disentangle these stories, but they are a typically Balkan web of lies, intrigue, intensity, self-pity and self-defence, which makes them all the more compelling.

"Brilliantly ventriloquises the voices of this mysterious, plundered part of Europe"

A Bulgarian living in Scotland, Kapka Kassabova holidayed on this border as a child. Although her upbringing in Sofia was relatively privileged, she shared the sense of entrapment—having emigrated to the West, she empathises with those lured to follow. In a wonderfully told episode, she is escorted over the Bulgarian frontier by a people-smuggler, a Pomack called Ziko, only to be trapped for days in a smoke-filled den in Greece with Ziko and his boozed-up pal, a couple of small-time crooks. She is free to leave, but imprisoned by her confusion, her lack of Greek and her politeness.

She explores other liminal spaces: the interface between reality and magic in the fire-walking rituals of the Strandja Mountains, her panicked descent into somewhere between sanity and madness when she eventually flees from Ziko down the Rhodope mountains—near where I saw the wolves—before he might or might not sell her on the black market.

Her writing powerfully weaves history, folklore, reportage and personal reflections. She can be lazy—beautiful places are ‘stunning’, the conquering Ottomans ‘rocked up’ and the way she derides British involvement in Greece during the Second World War and the subsequent civil war feels glib. (For more nuanced insights, read An Affair of the Heart by Dilys Powell.)

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

That aside, Border is illuminating, passionate and sometimes funny. It brilliantly ventriloquises the voices of this mysterious, plundered part of Europe, revealing the ironies of nationalism and the profound way in which ethnicity and displacement can affect the human psyche.

Border by Kapka Kassabova is published by Granta at £14.99

- - -

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

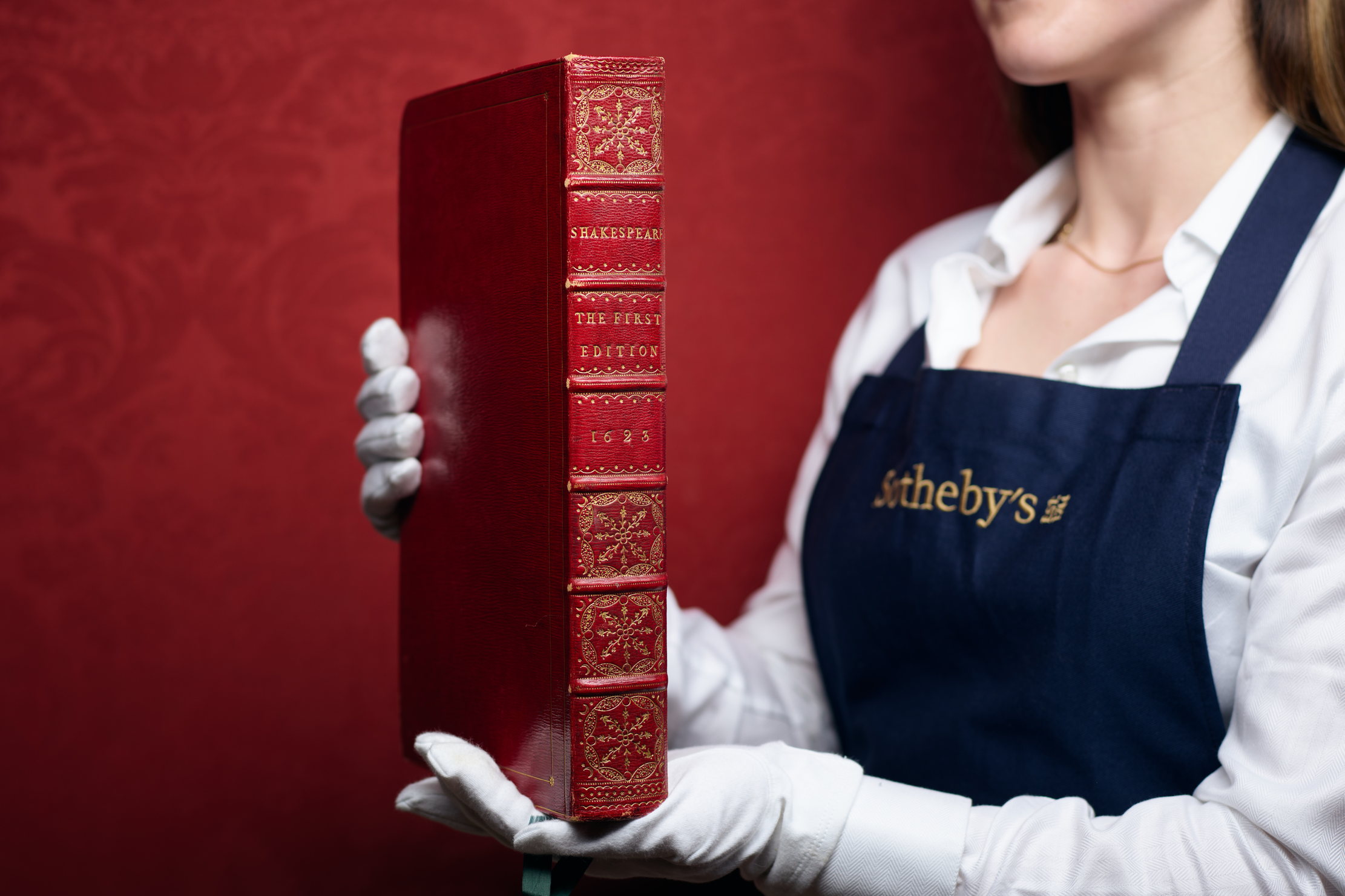

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow down

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow downThe glorious Andalusian-style villa is found within the Lomas de Marbella Club and just a short walk from the beach.

By James Fisher