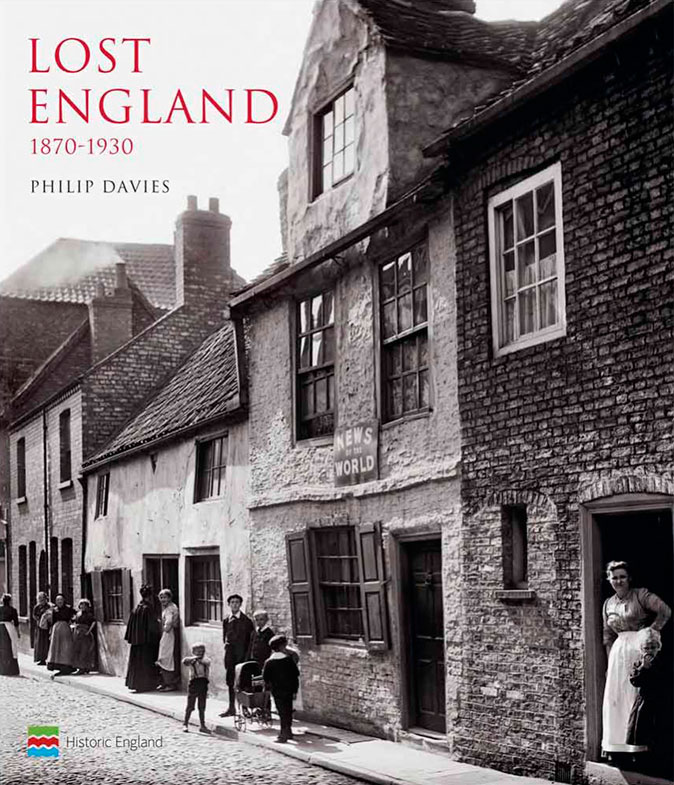

Book of the week: Lost England

Marcus Binney applauds a new book of photographs of metropolitan and rural England between 1870 and 1930.

The title Lost England suggests a treasury of lost wonders of English architecture recorded in deeply etched early black-and-white photographs. here, however, it means something completely different. Rather in the way we now use BCE (replacing BC) to mean ‘Before Common Era’, we might call the view of pre-1930 England presented in this sumptuous 560-page tome BME— Before the Modernist Era.

The buildings illustrated are almost all still with us, but they offer no glimpse of pioneering Modernism or the concrete eyesores that have placed such a blot on our high streets and city squares. Instead, they range from Thaxted’s medieval guildhall and Abraham Darby’s Iron Bridge in Shropshire to Preston’s imposing Grecian art gallery and the Liverpool Liver Building. Many have been handsomely restored and are well cared for.

Lost England: 1870–1930, which forms a sequel to Philip Davies’s best-selling Lost London: 1870– 1945, comprises an absorbing picture gallery of almost every monumental building type that graces England’s towns and cities: town halls and museums, law courts and libraries, universities and hospitals, opera houses and theatres. The public buildings of the northern cities rank high among the splendours and many can be visited to some degree.

Showy Victorian and Edwardian commercial premises in a rich mix of materials and colours also figure strongly, lively examples including Alexandra house in Leicester and the frothy Venetian Albert Buildings in the City of London. Also notable are the intentionally mighty premises of dozens of prosperous insurance companies, such as the terracotta-encrusted Star Life building in Manchester and the spiky Gothic Scottish Provident Institution in Birmingham.

Town halls form an astounding group. Leeds, by Cuthbert Brodrick, is as richly columned and pilastered as Castle Howard, Birmingham has a Corinthian temple to rival La Madeleine in Paris, Wakefield is an exhilarating Art Nouveau masterpiece and the Guildhall in Hull by Sir Edwin Cooper is grand enough to stand in new Delhi. Gone, alas, is George Gilbert Scott’s Preston, whose clock tower ran St Stephen’s Tower a close second—demolished following fire damage.

By contrast, Luton has a gleaming Portland stone town hall of 1936, which replaced the 1847 one burnt down after the Mayor failed to invite a single ex-serviceman to dinner at the Peace Celebrations in 1919.

Although the main focus is on cities, the book includes many evocative photographs of county and market towns, market crosses and spas and a rich gallery of medieval, Tudor and Victorian timber-framed houses and inns.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Some of the churches demand an architectural pilgrimage. Holy Trinity in Hull is the largest parish church in England and Boston’s Stump is so named because it was built—in the early 1500s—with the tallest parish church tower in the land.

Who took all these wonderful images? Surprisingly, we are not told, although a number are credited in the acknowledgements to Francis Frith. This was the age of large-format plate-glass photography, at which Country Life of course excelled. The medium achieved a range of sharp detail in both foreground and distance never since equalled, but here the skies, by contrast, are rather blank.

The effect on some photographs is rather deadening and, given that early photographers often coaxed out skies through careful printing, it raises the question as to whether the original photographers’ prints (far, far the best) were used or whether new prints were made from the old, mainly glass, negatives, or modern copy negatives used.

There is much fascinating material here about architecture, but it would have been nice to have had a bit more on the photography.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

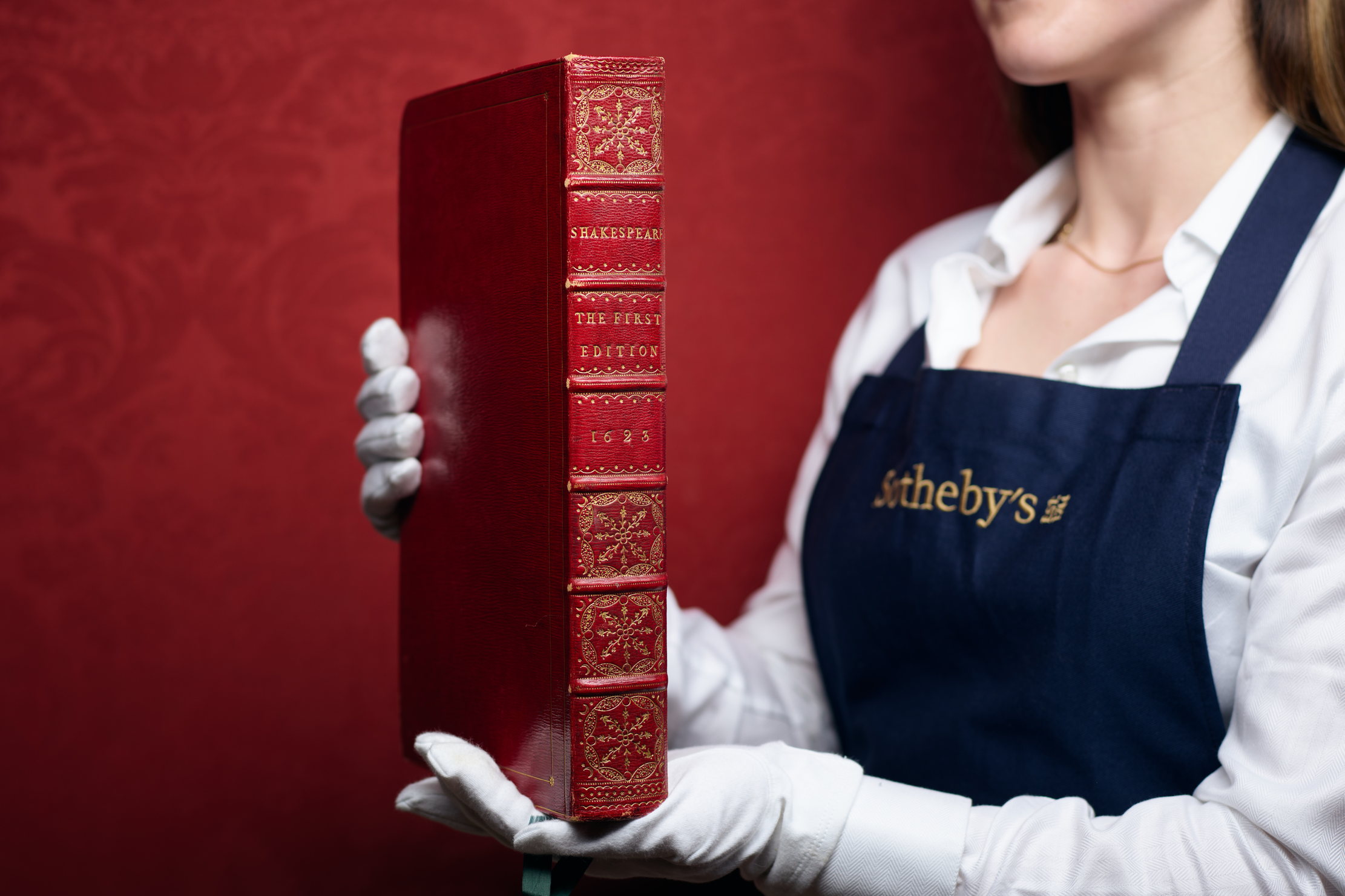

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow down

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow downThe glorious Andalusian-style villa is found within the Lomas de Marbella Club and just a short walk from the beach.

By James Fisher