Book Reviews: New war/history books

Philip Eade is moved by the effect of war on ordinary individuals

To order any of the books reviewed or any other book in print, at

discount prices* and with free p&p to UK addresses, telephone the Country Life Bookshop on Bookshop 0843 060 0023. Or send a cheque/postal order to the Country Life Bookshop, PO Box 60, Helston TR13 0TP * See individual reviews for CL Bookshop price

War/history

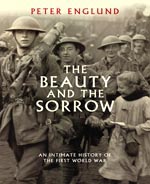

The Beauty and the Sorrow Peter Englund (Profile, £25,*£22.50)

The Quick and the Dead Richard van Emden (Bloomsbury, £20, *£18)

A Train in Winter Caroline Moorehead (Chatto & Windus, £20, *18)

With the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War now less than two years away, the Swedish historian and sometime war correspondent Peter Englund has come up with a new and innovative way of viewing the conflict, through the eyes of 20 ordinary individuals of various nationalities, ranging from a German schoolgirl to a Venezuelan cavalryman in the Ottoman army.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Their 1914-18 stories are told in a series of vignettes, arranged in chronological order and based largely on their own accounts.

One of the protagonists loves the war from start to finish, but the vast majority come to hate it and several are brought close to despair. Three die, two end up as prisoners of war, two become great heroes. A further two finish the war as physical wrecks, another loses his mind. Mr Englund's richly atmospheric ‘intimate history', is not, as he writes, about what the war was, but, rather, about what it was like.

The same could be said of Richard van Emden's book, in which the focus is on the suffering of the relatives left at home, although many of the letters quoted here testify to the horror and futility of what their men endured at the Front. The letters are unbearably poignant, not least those from soon-to-be fallen teenage soldiers from the trenches before they went over the top-many were convinced, justifiably, that they were about to die.

Some 192,000 British wives lost their husbands during that war, and twice as many children were left without fathers. One widow, on arriving at the Somme in 1919 to find her husband's grave, said: ‘I never expected this. I have tried to think of it, and of him in it, and of what hell looks like. But I never imagined such loneliness and dreadfulness and sadness in any one place in the world. One cannot imagine it. I thought I knew what it was like, but I only thought. I never felt until now.'

The heart-rending detail in Mr Emden's book is matched by Caroline Moorehead's profoundly shocking story of the 230 French women resisters who were sent by train from Paris to Auschwitz-Birkenau in January 1943. If they fared better than the trainloads of Jewish arrivals, 90% of whom went straight to the gas chambers, these ‘political prisoners' were, nonetheless, subjected to unbelievable brutality.

A few of the unfortunate Frenchwomen were gassed or shot, but the majority dropped dead in the mud and snow during the interminable roll calls or when being slave driven or beaten by SS guards. The squalor and overall deprivation in the camp meant that gangrene, typhus, dysentery and pneumonia were all rife, and Miss Moorehead's description of the conditions makes it incredible that as many as 49 survived. When she began her research in 2008, seven of the women were still alive, and, in telling their stories, she has produced an outstanding and important book, compelling and deeply troubling.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

About time: The fastest and slowest moving housing markets revealed

About time: The fastest and slowest moving housing markets revealedNew research by Zoopla has shown where it's easy to sell and where it will take quite a while to find a buyer.

By Annabel Dixon

-

Betty is the first dog to scale all of Scotland’s hundreds of mountains and hills

Betty is the first dog to scale all of Scotland’s hundreds of mountains and hillsFewer than 100 people have ever completed Betty's ‘full house’ of Scottish summits — and she was fuelled by more than 800 hard boiled eggs.

By Annunciata Elwes