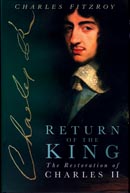

Book review: Return of the King: The Restoration of Charles II

An illustrious author gives a personal touch to a scholarly tale, says Sir John Ure

Return of the King: The Restoration of Charles II Charles FitzRoy (Sutton Publishing, £20)

Lord Charles FitzRoy has special qualifications to write this book: as a son of the 11th Duke of Grafton he is a direct descendent of the Duchess of Cleveland and Charles II who on the night of the king's triumphal entry into London at the Restoration 'retired into the willing arms of his new mistress, the voluptuous Barbara Villiers' (later to become Duchess of Cleveland and to give birth to the first Duke of Grafton).

But the author has much more than a family link: he has researched the events leading up to the Restoration with scholarly skill. Exactly how problematical this restoration was is often forgotten, as the most popular source of information on the subject is the opening volume of Pepys's diary, and Pepys was only involved in the final, happy and uncontested stage of the King's return by sea from his exile in Breda.It is the author's achievement that he has analysed and recounted the close infighting between the different contending factions after the death of Oliver Cromwell and during the short-lived tenure of his son the likeable, but ineffectual Richard Cromwell.

That succession was aptly described by the royalist who declared 'the Vulture died, and out of his ashes arose a Titmouse'. The different Cromwellian generals and the members of the notorious Rump Parliament all had their own ideas on how the English people should be governed. In the end, it was a nationwide desire to avoid further internal strife and anarchy a sentiment appreciated and manipulated by General Monck that allowed the King to return almost by default. This was no dashing cavalier uprising, but a cautious, negotiated, consensus decision.

Indeed, so unopposed was the King's ultimate return that he memorably remarked: 'I doubt it has been my fault, that I have been absent so long for I see nobody that does not protest he has ever wished for my return.' It was Charles II's great achievement that he managed, largely by making the Church of England as inclusive as possible, to hold this consensus together. The nation was tired of Puritanism, but not prepared (as James II was to discover to his cost) for a reversion to Catholicism. The Merry Monarch had a shrewd eye for public opinion, as well as for voluptuous ladies.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producers

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producersStormzy, Rihanna and the Rolling Stones are just a part of the story at Osea Island, a dot on the map in the seas off Essex.

By Lotte Brundle

-

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The Season

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The SeasonHere's how to navigate this summer's top events in style, from those who know best.

By Madeleine Silver