Book of the week: The Roy Strong Diaries 1988–2003

Despite moments of grief and dismay, Sir Roy’s latest volume of diaries is happier than his last, says Michael Hall.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

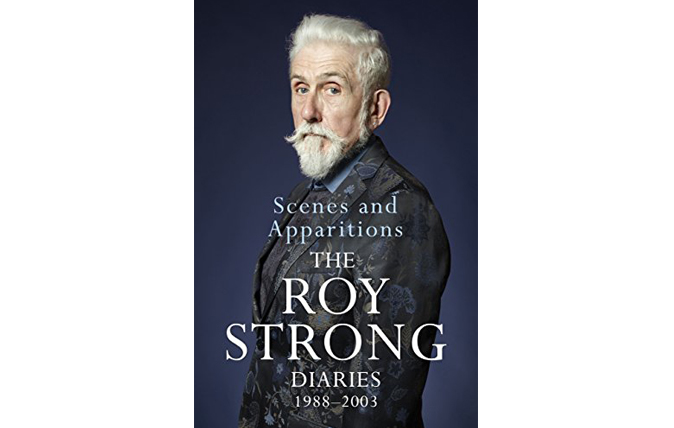

Scenes and Apparitions: The Roy Strong Diaries 1988–2003 (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £25)

Sir Roy Strong’s previous volume of diaries is so firmly imprinted on my memory that I’d forgotten it came out as long ago as 1997. Covering the years 1967 to 1987, it was a sharp self-portrait of a cultural leader at the centre of metropolitan life, as director of first the National Portrait Gallery and then the V&A. This new volume begins just after he has—with relief—quit the V&A for life as a freelancer in the country, earning his money from television, books and journalism—not least for Country Life.

Like everyone in his situation, Sir Roy frets about deadlines and finding enough money to pay the next tax bill, but, compared to the last volume, which was eye-openingly frank about the miseries of running a major museum, this is a happy book. Although it encompasses tragedy—the murder of his friend Gianni Versace—and concludes in grief, with the death from cancer of his wife, Julia Trevelyan Oman, it is, in essence, a portrait of emotional and creative fulfilment, in marriage, friendships, work and, in particular, the celebrated garden that he and his wife created at their Herefordshire home, the Laskett.

Sir Roy tells us that he often didn’t keep a daily diary, but would write up events that seemed to him worthy of record. as a result, there are some splendid set-piece descriptions of occasions ranging from Elton John’s 50th-birthday party (‘like an over-grown schoolboy dressed as Prince Charming at the ball’) to a concert for the Queen Mother at Buckingham Palace (‘any sense of style and much else seems to have left the place’).

there is plenty of comedy, often at Sir Roy’s expense: when he sits for a portrait by Lord Snowdon, the result ‘was a cross between Heathcliff and a rent boy in old age, but, as Tony said, “there’s the cover for your next book”’. There’s a very funny account of entertaining the irredeemably urban Antonia Fraser and Harold Pinter at the Laskett—their ‘Mercedes was iced up so Julia went to the garage and brought back her plastic scraper. Harold stood and looked on as Julia cleaned the windows and then, when she’d finished, stepped forward and said: “You’ve missed that bit.” Exit Pinters’.

Gardens and gardeners feature prominently—Susana Walton at La Mortella, Ian Hamilton Finlay at Little Sparta and Rosemary Verey’s 80th-birthday party are highlights. Sometimes the array of names is dizzying: boldly, Sir Roy has dispensed with footnotes, relying instead on a (less than comprehensive) list of characters at the back of the book. at first, I was disconcerted, but the absence of notes keeps the book buoyant and easy to read.

There is shadow as well as sunshine in the garden. Sir Roy is dismayed by the British political establishment’s indifference to heritage, which develops an aggressive edge after the Labour landslide of 1997. By the time of the 2001 general Election, he has come to detest New Labour: ‘I loathe their derision of the monarchy, Church, law, of any ancient established institution or tradition.’ That explains why his major books of the period, notably The Story of Britain, have such a strong political agenda.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Sir Roy’s liberal Anglo-Catholic faith is central to his life and, in 2000, he was made high Bailiff and Searcher of the Sanctuary at Westminster Abbey. This gave him an official place at many of the great royal ceremonies of the past 15 years, including the ‘extraordinary and very moving’ lying-in-state and funeral of his old friend the Queen Mother in 2002.

The year before, the Royal Maundy had been distributed at the Abbey: ‘It brought tears to my eyes. The ancient prayers made me realise that these must have been used for centuries. Gloriana herself must have heard them.’ Nobody but Sir Roy could have written that and I fervently hope that he doesn’t keep us waiting another 20 years for the next instalment.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.