Book of the week: The Last Royal Rebel

David Gelber is gripped by a new biography that redefines the reputation of Charles II’s amoral but courageous illegitimate son.

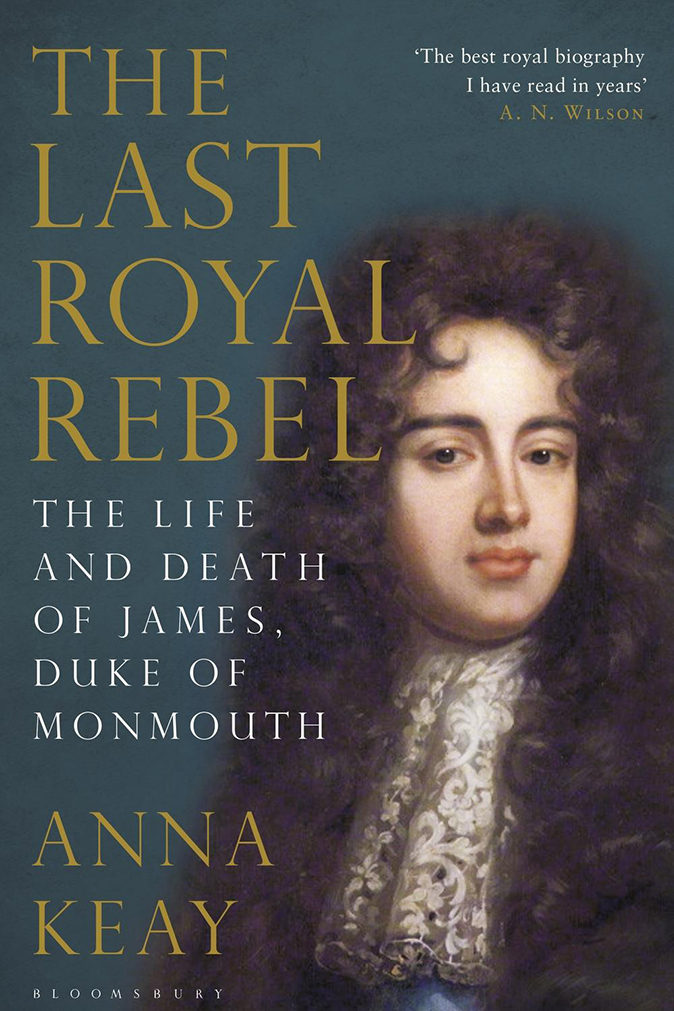

The Last Royal Rebel Anna Keay (Bloomsbury, £25)

Buy this title for for £22 at the Country Life Bookshop

No man who appeared so attractive to his contemporaries, figures in history as so worthless and contemptible,’ declared the historian F. C. Turner of James, Duke of Monmouth. Few scholars have departed from this scornful assessment of the eldest and most indulged of Charles II’s illegitimate children. Indeed, in his philandering, carousing and weakness for any passing fashion, Monmouth has become an emblem of the dissi- pation of the Restoration Court. The names of the hundreds of West Country folk who paid with their lives after his unsuccessful rebellion against his uncle, James II, in 1685 have stood as a roll call of his defects.

In this powerful new biography, Anna Keay turns the prevailing image of Monmouth on its head. She makes a persuasive case for him as a serious and even principled political actor. She argues, too, that he was a brave and resourceful soldier, ‘in person wherever any action or danger was’. Her book could serve as a manual for the gainful employment of any illegitimate child born to a sovereign.

In spite of the book’s title, there was nothing regal about Monmouth’s early years. He was born in Rotterdam in 1649, months after the execution of Charles I, the bastard son of a penurious and exiled monarch by a woman condemned as a whore. He spent his first decade as a refugee, dragged across Northern Europe as his mother groped for cash and lodging.

He didn’t set eyes on his father until the age of seven and, at nine, had still not grasped the basics of the alphabet, yet three years after Charles II’s return to London, he found himself at the pinnacle of English society, ‘smothered... in love’ by the King, showered with honours and betrothed to one of the most eligible heiresses in the land.

Enjoying all the trappings of royalty save a place in the order of succession, he was sent by Charles to lead English armies and diplomatic missions in the Low Countries and France, his illustrious descent adding prestige to whatever party he joined.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Dr Keay is too serious a scholar to ignore Monmouth’s shortcomings. In his heyday, one contemporary noted, ‘all the gay and beautiful of the fair sex were at his devotion’. As he awaited execution, Monmouth himself confessed that he had ‘for a long time lived a very dissolute & irregular life... being guilty of frequent breaches of the conjugall vow’. Instead, she teases out the connections between the personal and the political.

Sex, she demonstrates, was not merely a subject for bawdy jokes, but a matter of national importance. Before the Restoration, Cromwell’s government sought to exploit Monmouth’s very existence to prove that Charles was morally unqualified to rule. Charles’s inability to father an heir with Catherine of Braganza and the obnoxiousness of the next in line, his Catholic brother James, to swathes of the population meant that royal reproductive practices became a burning political issue.

In this environment, Dr Keay reveals, the King’s affection for Monmouth had far-reaching and eventually fatal consequences. Charles never seriously considered legitimising Monmouth. Nevertheless, by fondly referring to him as ‘our dearly beloved son’, omitting the qualifier ‘natural’ to signify his illegitimacy, he inadvertently stoked rumours that he had secretly married Monmouth’s mother.

During his father’s lifetime, Monmouth quashed suggestions that he was the king’s rightful heir, but after Charles’s death in 1685, he allowed himself to be talked into leading a futile uprising against his uncle. After his army’s defeat at Sedgemoor, he fled the battlefield. The former Court gallant was eventually captured in a ditch and beheaded as a traitor.

This penetrating and superbly researched biography is a reminder, above all else, of the dangers of showing too much love.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to last

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to lastKitchen and joinery specialist Artichoke had several clever tricks to deal with the fact that natural wood expands and contracts.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025Friday's quiz is an Easter special.

By James Fisher