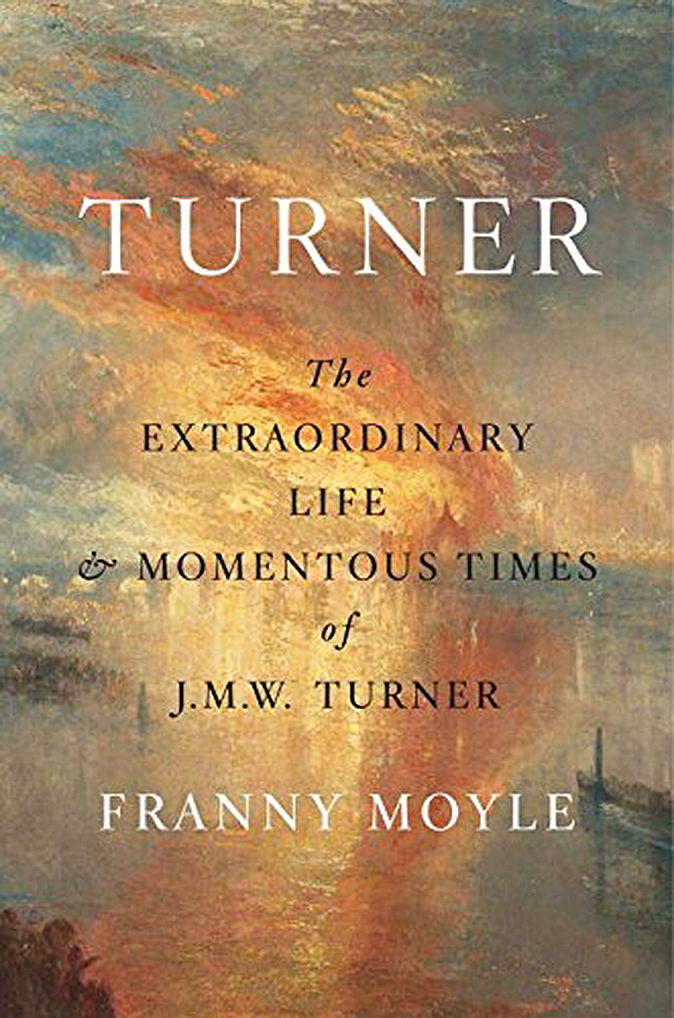

Book of the week: The Extraordinary Life and Momentous Times of J. M. W. Turner

Huon Mallalieu finds old traditions and newly discovered truths in this enjoyable retelling of Turner’s life.

The Extraordinary Life and Momentous Times of J. M. W. Turner By Franny Moyle (Penguin Viking, £25)

It is is extraordinary to think that there is still more to be written about Turner, given the shelves-full of biographies, studies and catalogues that have been published since Ruskin’s advocacy in the 1840s and Thornbury’s 1862 Life.

Most recent is the first volume by Eric Shanes (reviewed here April 27, 2016), with another and an expanded electronic version to come. Mr Shanes digs deeply into previously untilled archive material and it is likely that, when complete, his biography will leave only a few corners of the life still to be investigated, although the works themselves will no doubt still be reinterpreted and evaluated by new generations of art historians.

In the meantime, we have this further account of the life by Franny Moyle, who has come to biography by way of Arts pro- gramming and television pro- duction at the BBC. Her first book, Desperate Romantics: The Private Lives of the Pre-Raphaelites, was better than the TV series based on it, but sometimes relied more on good traditional stories than recent research. Her second biography, devoted to Constance Wilde, wife of Oscar —which I have yet to read—grew from a large cache of unpublished correspondence she uncovered and must change the conventional view of her subject.

Those books and her latest on Turner are linked in that each, in part, concerns the artistic life and development of 19th-century Chelsea. Turner opens and closes with the artist’s last years and death in the ‘secret’ second home by the river where he lived with Sophia Booth and was known locally as ‘Admiral Booth’. After his death in December 1851, various accounts were put about in order to avoid scandal, includ- ing an improbable-sounding tale of Hannah Danby, his former mistress and the housekeeper at his official residence in Mayfair, becoming worried at his long absence and finding the Chelsea address in a coat pocket.

On the off chance that he might be there, she is said to have turned up days before his death and then informed Henry Harpur, Turner’s cousin and solicitor, of his whereabouts. In fact, Harpur had already visited ‘many times’ during Turner’s last illness and it is not impossible that Sophia and Hannah had their own line of communication—perhaps Turner’s assistant at Queen Anne Street, who was the brother of his Chelsea barber.

In fact, several Chelsea people could connect the obscure ‘Admiral’ to the famous artist. Charles Martin, a fellow RA, lived within a couple of hundred yards at Lindsay House and, according to his son, was invited to visit at least once. The rector Charles Kingsley was uncle to Turner’s friend and patron the Rev William.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Here, Miss Moyle may have accepted the traditions too readily, but, elsewhere, she has delved profitably. Like Mr Shanes, she details the manoeuvrings undertaken by Turner and his father in order to have his mother committed to mental asylums at the least cost to themselves and also the duplicity that enabled Sarah Danby, Hannah’s aunt and predecessor, to continue to claim an ‘unsupported’ widow’s benefit.

Miss Moyle tells a very good story. She is sound on the art without allowing art historicism to weigh her down. She is also excellent on the complicated politics of the Royal Academy. We get a feel for the man in all his cantankerousness and eccentricity, but she also brings out the humour and —at least after he had made his own fortune—the generosity, especially towards his fellow artists.

One tiny nit to pick is the repeated description of the miniaturist James Nixon as the brother of Turner’s early patron, the Rev Robert Nixon. They were not brothers and almost certainly unrelated.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

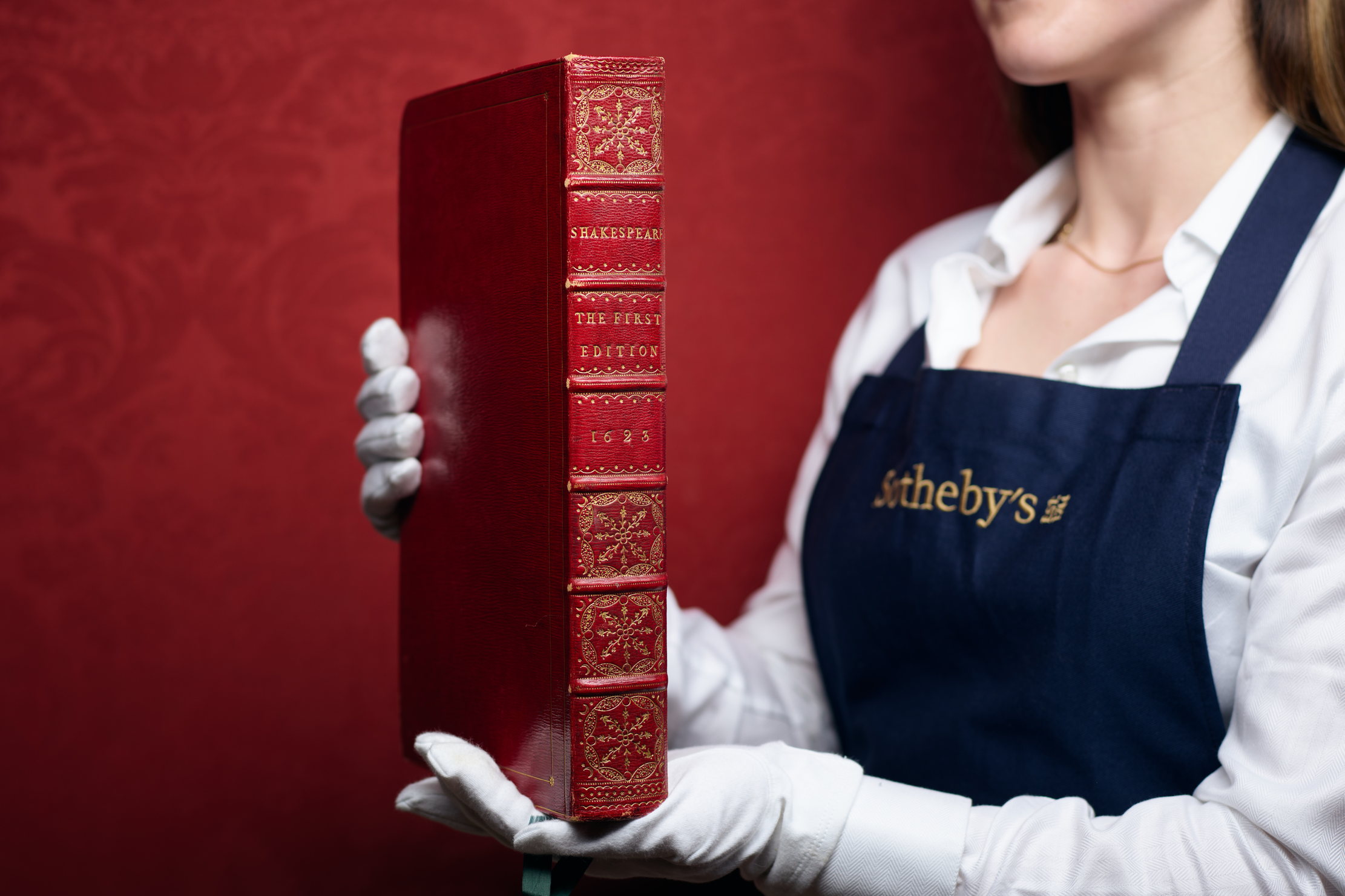

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow down

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow downThe glorious Andalusian-style villa is found within the Lomas de Marbella Club and just a short walk from the beach.

By James Fisher