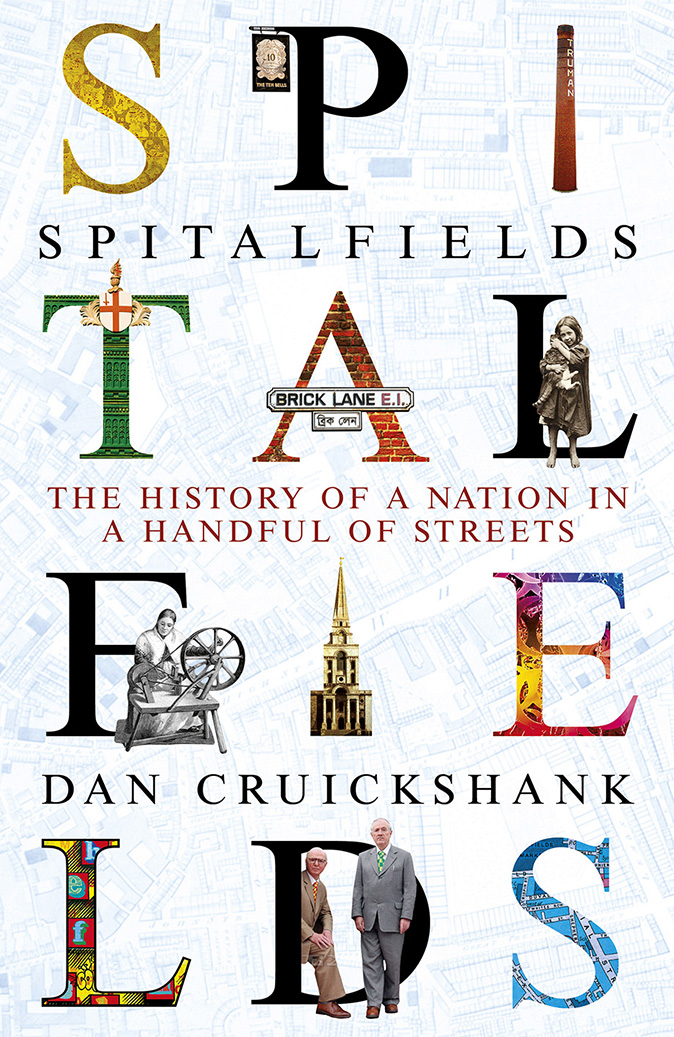

Book of the week: Spitalfields: The History of a Nation in a Handful of Streets

Dan Cruickshank’s history of Spitalfields also contains a warning about its future, discovers Michael Murray-Fennell.

Spitalfields: The History of a Nation in a Handful of Streets By Dan Cruickshank (Random House Books, £25)

Architectural historian Dan Cruickshank first moved to East London’s Spitalfields in 1977, into 15, Elder Street, the original occupant of which was almost certainly one of the Huguenot weavers whose skill with silk ensured the area flourished during the 18th century. since those early days, when Mr Cruickshank repaired the four-storey Georgian house and kept himself warm by burning discarded pallets from the nearby (and now closed) fruit-and-vegetable market, he has explored the neighbourhood in depth, on foot and through the archives.

Over the past four decades, he has also campaigned to save its buildings and streets from unsympathetic development. Now, he has written a history—10 years in the making—that does justice to Spitalfields’ story, but also warns of the district’s perilous future.

Spitalfields stretches approximately from the eastern edge of the City of London to Brick Lane. Mr Cruickshank traces the origin of its name across a number of 16th-century maps, first as ‘The Spitel’, then ‘The Spitel Fyeld’ and finally ‘The Spitel Fields’ or the hospital in the fields, referring to the medieval Augustinian Priory of St Mary, just outside the City wall. Here, the sick and the destitute were cared for and the tower was a landmark for travellers to London.

Spitalfields, Mr Cruickshank writes, was ‘border territory’, where outcasts and outsiders could seek refuge. From Roman times to today, he charts the different waves—persecuted French Huguenots, Irish Catholics, Jews from eastern Europe and, later, the Bangladeshi community—who all made it their home.

Throughout the book, Mr Cruickshank covers the raising of Spitalfields’ major buildings—the area’s iconic Christ Church by Nicholas Hawksmoor, for instance—but it’s the more modest architecture that interests him the most: the ‘humble and unglamorous—so in consequence unappreciated, undervalued and unprotected’. These include small Georgian workshops and a 1797 soup kitchen on Brick Lane that today is a Bangladeshi supermarket (the author visits it and feels among its aisles ‘the presence—even if very faint—of outcast Spitalfields, the shade of desperate people who gathered in this space for nearly one hundred years’).

He also fills the pages with the people who lived in Spitalfields over the centuries: Elizabethan actors and playwrights, 18th-century weavers with their flowerpots and singing birds and the Victorian poor who drew the attention of philanthropists, social reformers, and journalists. Riots and violence often erupted on the streets and Mr Cruickshank places these incidents within the context of the wider national and global social changes of the day.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In 1719, 4,000 weavers marched through Spitalfields protesting at the import of cheap cotton from India; 50 years later came the horrifying story of a weaver caught in the middle of a wage war being hunted through the streets by a mob and killed.

Change has always been a characteristic of Spitalfields and yet, at the end of the book, there’s a sense that the qualities that make the area so special and which have survived for so long are now under threat. Mr Cruickshank writes perceptively and honestly of the double-edged sword that is gentrification and of how the successful efforts by him and others in the 1970s and 1980s to rescue and repair the historic buildings have contributed to rising prices and rents.

Now, potential development schemes risk robbing Spitalfields of its rich mix of low-rise historic houses and street patterns, replacing them with monolithic, high-rise commercial buildings. This book then, as well as being a fascinating account of a unique area of London, is a timely warning that helps us to appreciate what the city and country risk losing.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'The Paper Mill estate is a picture-postcard in the Garden of England.

By Penny Churchill

-

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes