Book of the week: SAS: Rogue Heroes

Barney White-Spunner is swept along by this riveting account of the renowned special fighting force—the individuals as well as their actions.

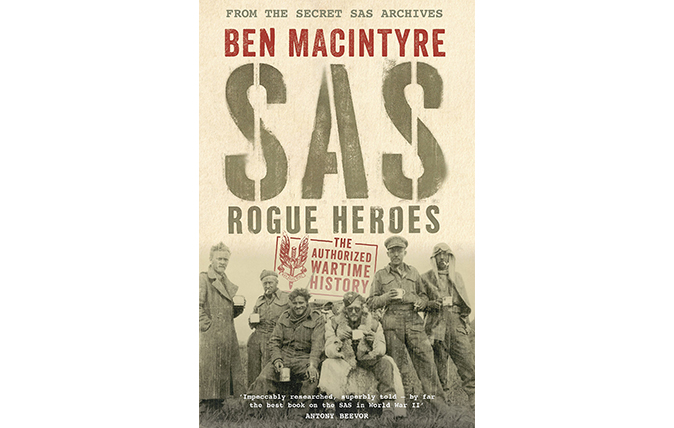

SAS: Rogue Heroes Ben Macintyre (Viking, £25)

The SAS has long excited the British public. Images of its daring activities, from the North African desert during the Second World War to London’s besieged Iranian Embassy in 1980, have become iconic. The regiment has also long excited authors, largely because of the British Government’s flat refusal to comment on anything connected with the Special Forces—and quite right, too: there are some things that must remain a matter of trust between the taxpayer and those we elect to govern us, whose primary responsibility remains our security.

The Second World War is, however, long enough ago for the usual caveats to be relaxed. Ben Macintyre has now written the ‘authorised’ history of the regiment, covering the period from 1941, when it was founded in North Africa, to 1945. He emphasises that this is an authorised as opposed to an official history, because, although he had access to the regimental archive, and particularly its war diary, he offers his own interpretation of its exploits. The end result is both well informed and very readable.

It would be almost impossible to make this story dull. Lying in a hospital bed in Cairo recovering from a parachuting accident caused by an illicit jump with an improvised canopy that got caught round the aeroplane’s tail fin, an otherwise undistinguished Scots Guards officer dreams up the idea of dropping small groups of determined men deep behind enemy lines to raid enemy airfields.

Against all the odds and the layers of ‘fossilised shit’, as he rather unkindly called the army staff, he gathered a group of 60 like-minded men and planned their first parachute operation for November 1941. Launched, against advice, in the teeth of a storm, it was a disaster; 21 men returned out of 55. However, David Stirling was not deterred. Although parachuting would remain core to SAS operations, the preferred method of insertion now became via the Long Range Desert Group, which had already been successfully inserting small reconnaissance parties through the great sand sea of the Qattara Depression.

The SAS went on to play a major part in the defeat of Axis Forces in North Africa. Rommel wrote in his diary that it had as much effect psychologically on his men as it did physically, although Paddy Mayne, Stirling’s second in command, destroyed more aircraft during the war than any other individual—he just did so on the ground.

Support from Churchill, whose son, Randolph, Stirling cleverly recruited to his ranks, ensured the regiment’s future and it would also play a key part in operations in Europe, particularly over D Day.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

What is so interesting about this book is that the author looks at each SAS man as an individual. There’s a long-held myth that SAS members are all super-fit psychopathic killers. This is, of course, rubbish and he points out that Stirling set the pattern for recruiting the intellectual, the linguist and the specialist, as long as they were fit, brave and determined.

Above all, Rogue Heroes is the story of men in combat and how it affects them. SAS casualties during the war were extraordinarily high, partly because of the nature of its operations, but also because of Hitler’s now infamous ‘Commando Order’, which ordered all Allied soldiers taken behind enemy lines to be summarily executed. Many SAS soldiers were betrayed by Schurch, the British Fascist, who was an enemy agent and the only serving British soldier to be hanged for espionage during the war.

In addition to its physical effect on the ground, it’s worth contemplating two other really valuable contributions made by the wartime regiment. First, it gave a huge boost to morale in North Africa at a time when many British soldiers considered Rommel unbeatable. Second, and we should all be very grateful for this, it was the forefather of today’s Special Forces, who do so much to keep us all safe.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Burberry, Jess Wheeler and The Courtauld: Everything you need to know about London Craft Week 2025

Burberry, Jess Wheeler and The Courtauld: Everything you need to know about London Craft Week 2025With more than 400 exhibits and events dotted around the capital, and everything from dollshouse's to tutu making, there is something for everyone at the festival, which runs from May 12-18.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Everything you need to know about private jet travel and 10 rules to fly by

Everything you need to know about private jet travel and 10 rules to fly byDespite the monetary and environmental cost, the UK can now claim to be the private jet capital of Europe.

By Simon Mills