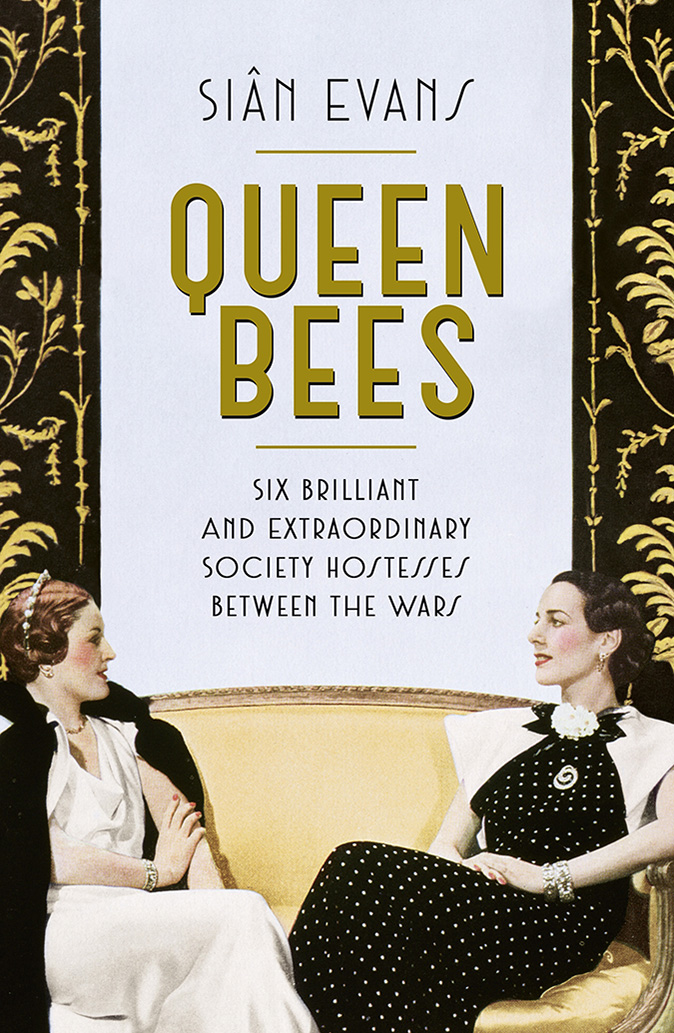

Book of the week: Queen Bees

This new book casts a spotlight on the women who led English Society at the beginning of the last century, says Martin Williams.

Queen Bees by Siân Evans (Two Roads, £20)

London it has been said, is a man’s town. One need only think of Savile Row and Jermyn Street, Horse Guards and Clubland, to appreciate why. So it is perhaps ironic that, for the first few decades of the last century, the capital should have been carved up between the indomitable hostesses whose exploits are chronicled by Siân Evans in her wonderfully readable new book.

Of the sextet, the most widely known was probably Nancy Astor, the first sitting female Member of Parliament, but, in terms of influence, she was more than matched by her fellow Queen Bees: Mrs Ronnie Greville (Maggie), Mrs James Corrigan (Laura), Lady Colefax (Sybil), Lady Cunard (Emerald) and the Marchioness of Londonderry (Edith). At the time, reporters and commentators were punctilious in calling them by their married names and titles, and it is by those same names and titles that their legends have descended.

In virtually every other respect, the Queen Bees far outshone their drone-like husbands, reigning as the arbiters of fashion and the makers (or breakers) of careers and reputations.

English High Society has always been permeable, admitting outsiders of peculiar talent and tenacity. Even so, it is astonishing that, in an era so governed by implicit beliefs in class and breeding, Miss Evans’s protagonists were able to climb to the top of the heap.

Of the six, only Lady Londonderry was aristocratic. Sybil Colefax was the wife of a barrister who was knighted and Maggie Greville derived her substantial fortune from her Scottish brewer of a father— who was not married to her mother, a domestic servant, at the time of her birth. three weren’t even English: like Nancy Astor, Laura Corrigan and Emerald Cunard were Americans and both grew up in impecunious circumstances.

Reading this book, it is abundantly clear that considerable dexterity was required by the Queen Bees to sustain their roles in their gilded hive. Unpalatable facts about their antecedents were expunged, enemies were neutralised and alliances formed. To some degree, each was a self-creation. When she was well into middle age, Lady Cunard abruptly declared that she would no longer answer to ‘Maud’, adopting instead the more flamboyant moniker of ‘Emerald’.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

When the trajectory of one Queen Bee crossed with another, sparks could fly. Aggressively pursuing the latest ‘lions’ to add lustre to their guest lists, their rivalries were intense. Virginia Woolf observed with wry amusement the look on Lady Colefax’s face when a message arrived from Lady Cunard, inviting the famous author to dinner. It reminded her, she said, ‘of a tigress when somebody snatches a bone from its paws’.

Ruthless, snobbish, cruel and downright silly, the Queen Bees could be all of those things, yet they subscribed wholeheartedly to the principle of noblesse oblige and, when war was declared in 1939, they more than proved their mettle.

Nancy Astor worked tirelessly for the relief of her bombed-out constituents in Plymouth. Draped in jewels, Maggie Greville defied the Luftwaffe from her suite at the Dorchester (one might as well go out in style, after all). And Mrs Corrigan spent years flitting through France, selling valuables to Hermann Goering, then using the proceeds to fund the Résistance.

Still, old habits die hard. Returning to London after many adventures, she was spotted by Noël Coward at a New Year party hosted by Loelia, Duchess of Westminster. ‘Everybody was there,’ he later reported, ‘from Laura Corrigan to Laura Corrigan.’

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

John Sutcliffe — The man, the myth and the paint-naming legend behind Dead Salmon and Elephant's Breath

John Sutcliffe — The man, the myth and the paint-naming legend behind Dead Salmon and Elephant's BreathBy Carla Passino