Book of the week: Outlandish Knight

A new biography of Steven Runciman delves beyond the gossip to shed new light on a fascinating and complex personality, says Barnaby Rogerson.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

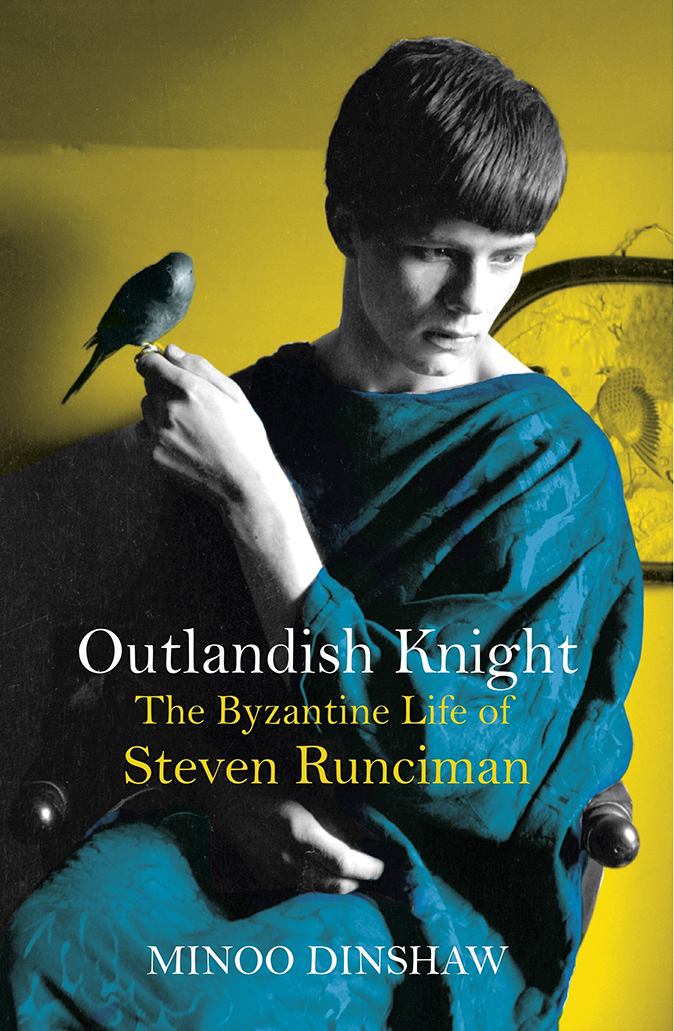

Outlandish Knight By Minoo Dinshaw (Allen Lane, £30)

This is a thumping 640- page biography about the great Byzantine historian best known for his three-volume A History of the Crusades, who, when interviewed by Country Life (July 2, 1998), remarked: ‘When I read biographies of my friends, I pray I shall not find a biographer.’

To further that end, Prof the Hon Sir Steven Runciman, Grand Orator of the Orthodox Church, Laird of the Hebridean Isle of Eigg and possessor of dozens of other wonderfully exotic titles and honours, liked to cover his tracks. Evidence was incinerated in an annual holocaust of letters, the exchange of which was otherwise one of his great pleasures. Yet, towards the end of his life, he was at work on an autobiography—all the better to frustrate a rival account—and had already compiled a hugely entertaining but partial memoir, A Traveller’s Alphabet.

Was this modesty about a biography all part of an elaborate game of manners? Runciman could spend years intriguing for a job only to ape surprised reluctance when finally offered it, or complain about being exhausted and exploited by yet another foreign lecture tour while actually loving every minute of ‘backing into the limelight’. He presented himself as an aloof and totally self-sufficient character, a scholar hermit in a tower of books, but also arranged for friends to drag him out for ceaseless rounds of parties.

It made life more artful, but it was also a vital survival skill for a man of his age and time. It helped protect him from the scandal, blackmail and thuggery that pulled down so many other homosexuals of his generation.

Other masks were also adopted. It often suited Runciman, who made the Dumfriesshire tower house of Elshieshields his final home, to project a Scottish Borders identity, charged with all the medieval romance of ruined abbeys and ancient feuds. In fact, the family fortune went no further back than his tough grandfather, a chapel-going Geordie and self-made shipping millionaire hewn from the Newcastle docks.

Another personal embarrassment was that his own father, a distinguished MP and long-serving member of the Liberal Cabinet, ended up deeply immersed in Neville Chamberlain’s betrayal of Czechoslovakia.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It would have been easy to turn a biography of Runciman into a hatchet job. Minoo Dinshaw has instead structured a complex book that reaches beyond these revelations to show us how his subject’s elective personae actually empowered his creativity. Without Runciman’s relentless snobbery, which fuelled his observation at a youthful distance of the Bulgarian and Romanian courts, he might never have become such a trusted intimate to the Greek royal family, which lent his anthropological zeal for Court gossip the human colour with which to animate the bare medieval chronicles of the past.

Similarly, the cool, emotional detachment of a lifelong bachelor allowed him to invest extraordinary levels of emotional energy into his writing.

As a result, Runciman broke out of the self-obsessed and critical academy in which he had been brought up—Eton, followed by Cambridge, where he got a First—and wrote passionate, vivid narrative history that achieved a vast, international audience.

He also somersaulted over centuries of Western-centric tradition to look at the past from the other side of the coin, be it the Arab face of the Crusades, the Sicilian reaction to conquering outsiders, the Bulgarian influence on Byzantium, the real faith of persecuted heretics or magic and the universalism of the Byzantine Orthodox tradition. And, like a multi-lingual story-telling bard of old, he told the sad stories of the deaths of kings that left his audience’s cheeks streaked with tears.

I was delighted to learn that this hero of mine was also a loving uncle, a good cook, an enthusiastic gardener, a considerate landlord and a collector of pretty objects and colourful friends. This biography is both funny and erudite and empathetic but critical as it chronicles a fascinating caste of dangerously charming spies, poet-scholars, scheming Oxbridge academics, dashing majors and clever queens.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.