Book of the week: Jacobites

Sarah Fraser enjoys a witty and pyschologically acute account of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s uprising.

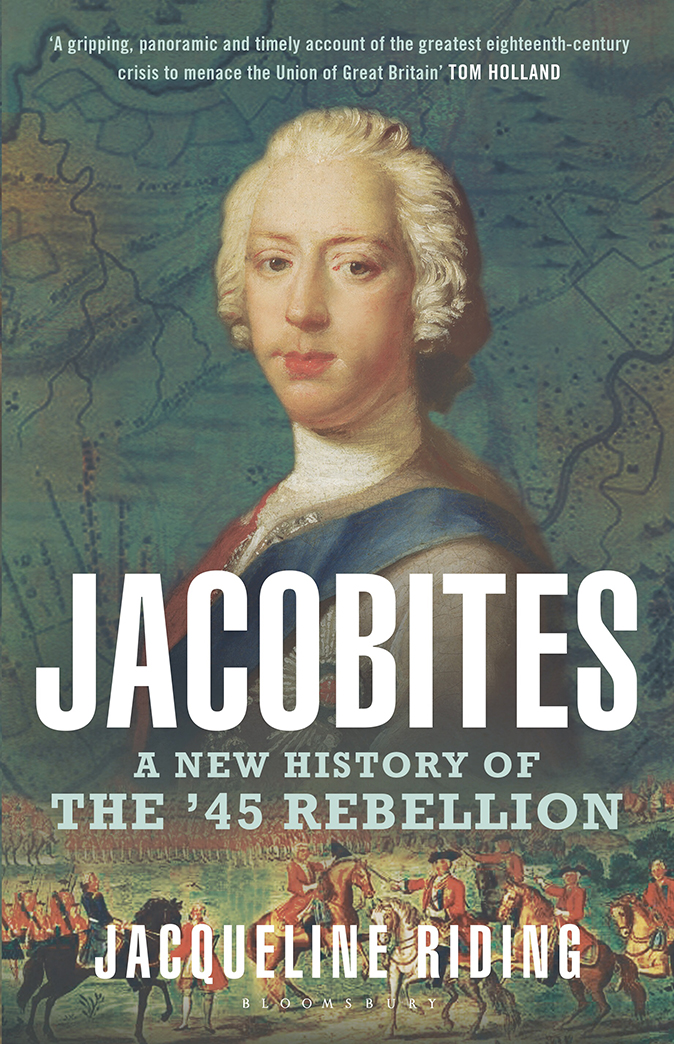

Jacobites by Jacqueline Riding (Bloomsbury, £25)

The story of Charles Stuart’s whirlwind plunge for the thrones of his ancestors is one of the great mythic dramas of British history. Reading Jacqueline Riding’s witty re-creation of that hectic odyssey, our own concerns—about the Union, Britain’s relationship with europe, terrorism threats—are fascinatingly refracted through her impeccably researched yet vigorously paced book. Jacobites deals with the tense, 14-month period between Charles’s decision to invade Britain and his furtive escape to France after Culloden.

To universal astonishment, the Jacobites had all Scotland within their reach just weeks after Charles landed. They could have remained in edinburgh to consolidate their gains and prepare to invade England, but this would have broken the Union, as Charles reconvened a Stuart Court and Edinburgh-based Scottish government.

Many of the Jacobite elite, the traditional Scottish ruling classes, wanted precisely that, in part because of the ‘frankly uninterested, London-centric’ Westminster political elite’s ‘attitude towards Edinburgh and Scotland’—illustrated, as the author points out, by the neglected state of Holyroodhouse, abbey and its environs.

Dr Riding also places the rebellion in the context of Britain in Europe. As she says, men like Pitt the Elder fiercely ‘opposed subsidies sent to assist Hanover during the War of the Austrian Succession’. Suspicions about their German king’s involvement of Britain in Continental Europe inspired many a Jacobite toast throughout the UK. From Versailles, Louis XV supported the Stuarts only in as far as it aligned with France’s aims. This was always the promise and limit of Bourbon support for their Stuart cousins.

Then there is the question of the Jacobites being ‘a mere parcel of desperadoes’, as one English clergyman loftily dismissed them. We labour under no illusion now as to what ‘a mere’ guerrilla, or inspired terrorist group, might achieve. British military leaders lamented the exhausting, enervating months playing catch up to a nimble, unpredictable, insurrectionary force. This fine new history of the ’45 rebellion shows us how all these issues played out.

Dr Riding has mined the archives to retrieve lost voices and her panoramic vision lets us hear the evolution of a national discourse—from disdain, to uncertainty, to panicked fantasying about cannibal Highlanders, to confidence, in the words of people like us. We hear them in concert with the big statements on tactics and strategic goals coming from the main actors in the tragedy— men such as Lord George Murray, the Duke of Cumberland and Prince Charles himself.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

About the Bonnie Prince, she is psychologically acute. His youthful conviction and charm carried more experienced, circumspect heads on a triumphant charge from the western Highlands to Derby.

The author hints that a greater, more solid character might have fought his way back from the catastrophe on Drumossie Moor to force at least mercy, if not territorial concession, from the British government. Charles was not that man and he condemned his followers to ‘pacification’ of the most violent, thorough-going kind, from which most never recovered.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.