Book of the week: Elizabeth Jane Howard: A Dangerous Innocence

Emily Rhodes enjoys a revealing portrait of a writer whose tempestuous love life was as thrilling as her depictions of romance.

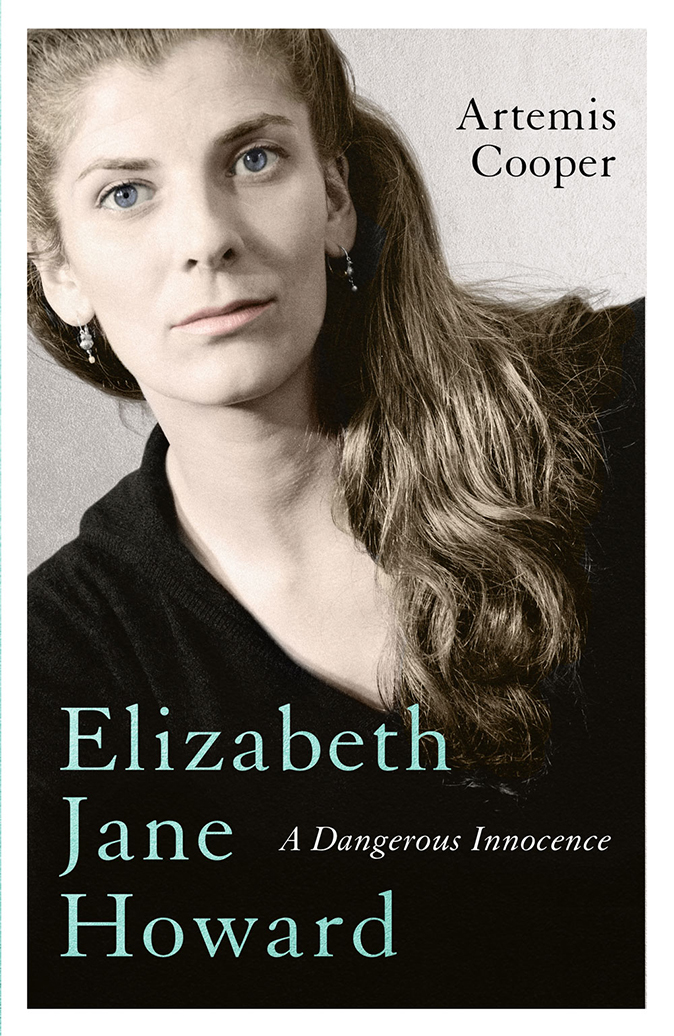

Elizabeth Jane Howard: A Dangerous Innocence by Artemis Cooper (John Murray, £25)

Elizabeth Jane Howard’s literary life was a potent cocktail of writing and sex. Her impressive career resulted in 15 novels—including her popular ‘The Cazalet Chronicles’—not to mention her work as a journalist, an editor for Chatto & Windus and artistic director of the Cheltenham Literature Festival. alongside these, and forming the meat of this riveting biography, Jane engaged in a string of love affairs, more often than not with members of the literati, including Arthur Koestler, Cecil Day-Lewis, Laurie Lee and Kingsley Amis, whom she married.

Artemis Cooper’s thorough, illuminating account draws on Jane’s own writing—her frank and revealing memoir Slipstream (2002)—as well as her personal correspondence and private papers, interviews and journalism. Miss Cooper takes care not to occlude Jane’s voice; instead, she sets the stage for her subject to speak.

So, in Jane’s own words, we enjoy, for instance, the hilarity of her sexual awakening at the skilled hands of (a married) Lee in Spain being somewhat undermined by needing the loo: ‘Desperate, I tried a door which revealed a middle-aged and completely bald man dressed only in a pair of black boots. He was angry, and then nothing like angry enough. I fled downstairs to the ground floor where there was the dining room or restaurant. I was wearing a night dress and cardigan...

‘The dining room was huge, brightly lit and absolutely full of men eating enormous hot dinners. Silence began to fall and increased to a breathless hush as I seized the nearest waiter by his sleeve and whispered “toiletta?” at him. He smiled, embarrassed, but eventually he got the point and indicated a sort of kiosk nearly in the centre of the room. it was small, vaguely round, and its walls stopped short a good foot from the floor. You could have heard a grain of rice drop as I made my way towards this goal, which was indeed a lavatory, of a kind.’

Miss Cooper notes that, in Slipstream, Jane wrote predominantly about her love affairs rather than her novels: ‘The question that absorbs her is why she made so many mistakes in her relationships.’ The same question absorbs Miss Cooper. She recalls interviewing her subject: ‘“I think you’re obsessed with my sex life,” she said sadly at one point. I blushed furiously and changed the subject. I wasn’t obsessed really, just fascinated.’

Fascinated indeed—not just for the juicy stories, but for the question that drives this biography: ‘How could this novelist, who wrote with such insight about men and women and what they do to each other, have taken herself through such bouts of emotional turmoil that invariably ended in disaster?’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Noting the frequency with which Jane’s life resurfaces in her novels, her biographer suggests, ‘she had to turn her experiences into fiction before she could make sense of them’. She also draws attention to Jane’s repeated use of ‘the character of the ingénue’, positing: ‘This childlike figure is the self she was so desperate to reclaim, the person she felt she had been before her mistakes had turned her into a glamorous, discontented femme fatale. if she could find the right man and marry him, she knew the healing process would start at once.’

‘A Dangerous Innocence’, the book’s subtitle, highlights the threat posed by this ingénue. Jane’s naïvety when it came to love proved perilous, not just for the many men who fell for her (and their wives), but also for herself. Her ‘insatiable desire for love and affection’ left her open to disappointment time and again; even in her seventies, she was taken in by a conman. Hers was a dangerous innocence indeed, but it makes for a wild ride—and a scintillating read—of a life.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.