Book of the week: Evelyn Waugh: A Life Revisited

A new addition to the shelf of Waugh biographies is crisp, diligent and sympathetic, says James Fergusson.

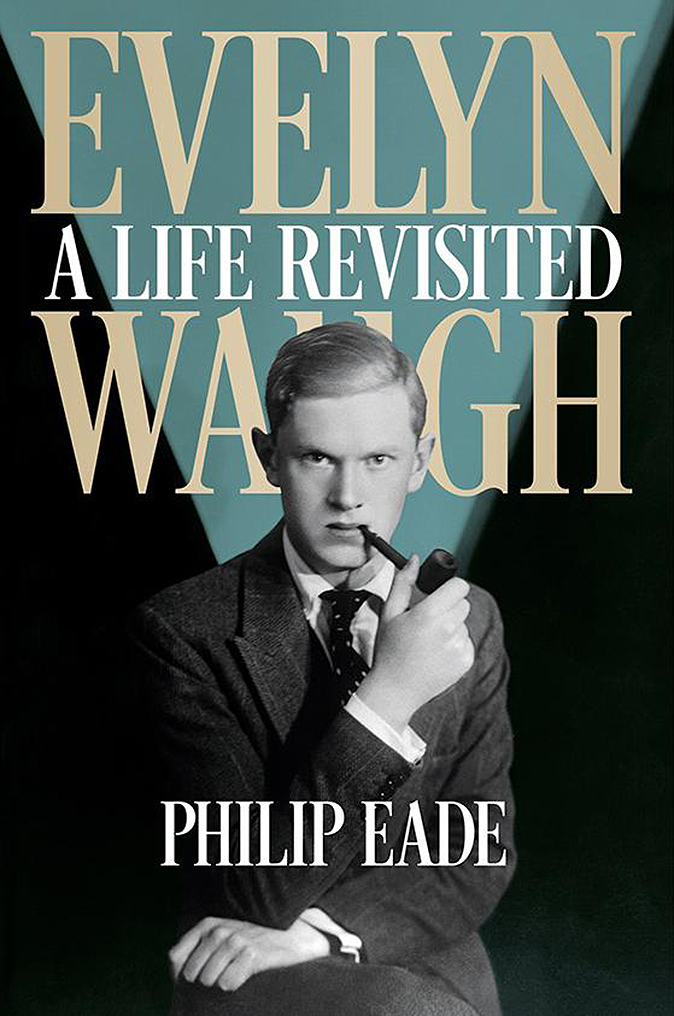

Evelyn Waugh: A Life Revisited Philip Eade (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £30)

For Anthony Powell, Evelyn Waugh was ‘the most naturally gifted writer of his generation’. He was also, Powell wrote on Waugh’s death, ‘one of the few people I have known who could be uproariously funny when drunk’ —which, from a reading of Waugh’s published diaries, was (when he wasn’t writing) most of the time. Often, he was more than drunk; he was ‘D. D.’—disgustingly drunk. That he wrote so much and so well was down to discipline and absence; he disappeared for weeks, to a pub outside Oxford or a hotel in Devon, and forsook all else.

The novels, each of such apparent facility, were the fruit of hard labour: Decline and Fall and The Loved One, both deliciously funny; A Handful of Dust, a dark masterpiece; the rich, nostalgic Brideshead Revisited; Scoop, the journalists’ favourite; and, perhaps his finest work, the wartime trilogy Sword of Honour. Their author was enormously successful in his lifetime, but, at the end, said his son Auberon, possessed by sadness.

What was it that made Waugh so impossible and unhappy? ‘Imprisoned in every fat man,’ wrote Cyril Connolly, the butt of some of Waugh’s cruellest jokes, ‘a thin one is wildly signalling to be let out.’ Waugh embodied contradictions. He was the fat man in tweeds in whom lurked, somewhere, the young ‘faun’ Harold Acton had discerned at Oxford. He was a man of kindness who could be brutal, even to his family. The father of seven children, he was, said his first wife, ‘I think... a homosexual at base’.

Waugh has been the subject of several thorough biographies: by his friend Christopher Sykes in 1975, by Martin Stannard (in two volumes) in 1986–92 and by Selina Hastings in 1994. Donat Gallagher has unearthed much further material and Alexander Waugh, Evelyn’s grandson, published Fathers and Sons, an extraordinary ‘autobiography of a family’, in 2004.

It was at the suggestion of Alexander, who is now editing a multi-volume ‘Complete Works’ for Oxford University Press, that Philip Eade undertook a new ‘half-centenary’ life. Among the unpublished material he draws on are love letters from Waugh to Teresa ‘Baby’ Jungman and the archive of Michael Davie, the editor of Waugh’s diaries and the only Waugh researcher to whom his first wife spoke openly.

Laura Waugh, Evelyn’s widow, sold rights to the diaries, without apparently reading them, to David Astor at The Observer in 1972; Davie was assigned the task of editing them. After they appeared, sensationally, in March–May 1973, he offered to work them up for book publication, to which end he wrote to and interviewed many of the protagonists.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

His invaluable archive, including interviews with Alastair Graham, one of Waugh’s Oxford lovers, and Evelyn Nightingale (née Gardner), Waugh’s first wife, ‘She-Evelyn’ or ‘Shevelyn’, now belongs to Alexander. ‘I looked very like a boy,’ Shevelyn told Davie. Does Waugh’s sexuality matter? Not strictly, but it may explain some of his torturous melancholy.

He had an awful relationship with his father, Arthur, a decent man who doted on Evelyn’s elder brother, Alec; his mother early upbraided him for his ‘quick and unkind tongue’. At his first school, he was a bully who terrified Cecil Beaton. At Lancing, ‘there were two Evelyns’, said his devotee Dudley Carew. ‘One was deadpan, like Buster Keaton. The other had bulging eyes and a ferocious voice.’ The one with bulging eyes became the public man, feared and frequently loathed.

Yet Waugh could show remarkable self-awareness. He was confessional as he proposed marriage to Laura Herbert (‘I am restless & moody & misanthropic & lazy’) and, in The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, he gave a vivid portrait of a man, himself, driven mad by prescription drugs: ‘Shocked by a bad bottle of wine, an impertinent stranger or a fault in syntax, his mind like a cinema camera trucked furiously forward to confront the offending object close-up with glaring lens; with the eyes of a drill sergeant inspecting an awkward squad, bulging with wrath that was half-facetious... He offered the world a front of pomposity mitigated by indiscretion, that was as hard, bright, and antiquated as a cuirass.’

Waugh was a genius. Mr Eade’s biography is crisp, diligent and sympathetic; his fresh material adds texture to this oft-told story and he particularly champions his subject over his war record in Crete. But the overall picture remains bleak. ‘Poor Wu,’ wrote Diana Cooper, a clear-eyed friend. ‘He does everything he can to alienate himself from the affection he is yearning for.’

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

‘It had the air of an ex-rental, and that’s putting it politely’: How an antique dealer transformed a run-down Georgian house in Chatham Dockyards

‘It had the air of an ex-rental, and that’s putting it politely’: How an antique dealer transformed a run-down Georgian house in Chatham DockyardsAn antique dealer with an eye for colour has rescued an 18th-century house from years of neglect with the help of the team at Mylands.

By Arabella Youens

-

A home cinema, tasteful interiors and 65 acres of private parkland hidden in an unassuming lodge in Kent

A home cinema, tasteful interiors and 65 acres of private parkland hidden in an unassuming lodge in KentNorth Lodge near Tonbridge may seem relatively simple, but there is a lot more than what meets the eye.

By James Fisher