The best First World War books

Barney White-Spunner sorts through the vast crop of books on all aspects of the First World War

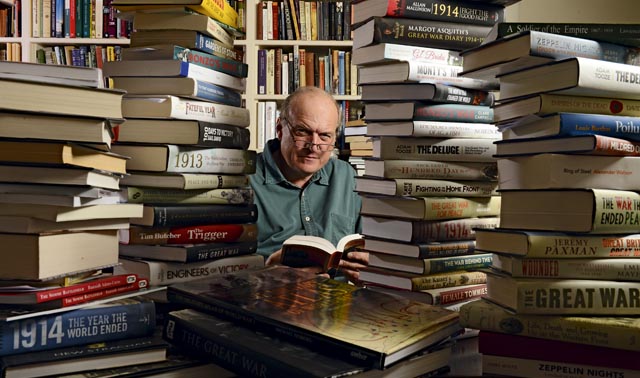

You can see from the accompanying photographs just how many books about the First World War we have been asked to review. I can count more than 56 now on my rather over-flowing sofa, but I still rejoice every time Rob the postman delivers yet another parcel.

It would be very wrong if historians were not taking this opportunity to analyse what caused this most dreadful of wars, why we had to fight for those four bloody years and what it meant to be either in the trenches or to experience the destruction of a once predictable life at home.

That we should be so mindful of their sacrifice is a fitting tribute to the more than 70 million men who were mobilised, of whom nine million paid the ultimate price (which works out at roughly 230 killed every hour of the war). Hopefully, every word written today, every action and every political move examined may just mean that future generations won’t have to suffer a similar catastrophe.

The sheer quantity of new books on the subject means, however, that a reviewer is pushed to do justice to the quality of the product. I must start with Michael Neiberg’s quite excellent The Military Atlas of World War I (Amber Books, £24.99 *£23.99). In the UK, we’ve become too focused on the Western Front and we tend to forget the global nature of the war. Not only does this atlas bring commendable clarity to that often difficult to follow campaign in France and Flanders, but it reminds us just how much the rest of the world suffered as well.

Did you know that, in 1914, French West Africa stretched from the Mediterranean to the Congo and that those colonies produced 569,000 men pour La France? Or that the Chinese Labour Corps provided 175,000 men for Britain and France in a vain attempt to secure their support against further Japanese incursion? This is an essential precursor for anyone wanting fully to understand just why this was a world war.

Another book to look at rather than read is The Great War (Jonathan Cape, £40 *£32), a wonderful photographic record; some of the shots will be well known to you, but most will not and, as a collection, they portray an image of just what those seemingly well-laid-out lines meant for those who fought there and the chaos, heat and flies that stalked them.

It’s still difficult to answer succinctly when someone asks you why fighting broke out in August 1914. For some, the war was the inevitable result of competition between archaic monarchies more concerned with dynastic survival than the interests of their subjects and the huge losses the result of their generals’ incompetence. For others, it was as important in the defence of freedom in Europe as the Second World War.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Margaret MacMillan’s The War That Ended Peace (Profile Books, £25 *£18) takes us a long way to understanding. This is a compelling, single-volume study of the background to the war, as well researched as it is enjoyable to read.

For those who want to read on, it’s still hard to beat Barbara Tuchman’s magnificent duo of The Proud Tower (1966), her story of the western world in the first decade of the 20th century, and The Guns of August (1962), being the history of the opening moves in the war itself and recently republished by Penguin (£10.99 *£9.89). Tuchman has that remarkable gift of making often complicated history read as if it were the most exciting adventure story. I’ve just listened to both volumes in my car on audiobooks and have found myself driving deliberately slowly to prolong the pleasure.

Two very different stories of the whole war are Jeremy Paxman’s Great Britain’s Great War (Viking, £8.99 *£8.54) and Hew Strachan’s The First World War (Simon & Schuster, £9.99 *£9.49). Mr Paxman writes with more sympathy than he has generally shown to hapless politicians interviewed on Newsnight, offering a sensitive portrait of what the war meant to the British people and how we reacted to its various pressures. It’s a very well-constructed story, combining the personal with the general and as hard hitting as you would expect without overdoing the gratuitous hindsight.

Mr Strachan offers, by way of contrast, the best one-volume political/military history of the whole conflict. Written with pace and clarity, it’s almost required reading for anyone trying to understand the anniversaries that will be marked over the next four years.

Some wonderful diaries are published for the first time this year and they offer predictably different perspectives. Corporal Louis Barthas was a French barrelmaker, conscripted at the beginning of the war, who kept notes of his major battles on the Western Front, including Verdun, which he transcribed into a manuscript in 1919.

Now published for the first time in English (it’s already well-known in France) as Poilu (Yale University Press, £25 *£22.50), his is one of the very best first-hand accounts of what the war meant to the ordinary soldier. His writing is lucid, cynical and conversational, recording what mattered to the men actually fighting, including some fairly damning testimony of his officers.

A most enjoyable anthology of extracts from various different First World War diaries and letters is From Downing Street to the Trenches (Bodleian Library Publishing, £19.99 *£17.99). Taken from papers in the Bodleian, its contributors range from politicians such as Asquith to regimental soldiers such as Ernest Makins of The Royal Dragoons and to Lawrence of Arabia and Bertrand Russell. Its great interest is how revealing it is about a lot of people whose private thoughts are often so different from their public persona.

It includes some entries from Margot Asquith, but I also recommend her Great War Diary 1914–1916, thoroughly edited by Michael and Eleanor Brock (Oxford University Press, £30 *£24), which is the chatty, high-society view of the Prime Minister’s wife from the outbreak of war until he had to go in 1916.

Less frivolous than it may at first seem, very interesting on the politics and high command and showing her gradual realisation of what the war really meant, it’s nonetheless a different view, as far as Londoners are concerned, from that of Jerry White’s Zeppelin Nights (Bodley Head, £25 *£20), the story of what living in the capital was like during the war years. The air raids form only part of the much wider picture of the cold, hunger and privation that was the daily lot of so many of the population.

We haven’t yet had very many books that look at the purely military aspects of the war; no doubt we will. But Allan Mallinson’s 1914 Fight The Good Fight (Bantam Press, £25 *£20) gets us off to a very strong start. He’s particularly good on why the British Expeditionary Force was as it was in 1914, the social and military pressures that had shaped it and how things could have worked out very differently in those first few months of fighting.

Lastly, although there seems no end to the stream, a most important and fascinating work is David Crane’s Empires Of the Dead (William Collins, £8.99 *£8.54), the story of how Fabian Ware, a volunteer ambulance commander, horrified at the cavalier treatment of the dead in 1914, started his move for the proper recording and burial of every Allied soldier who was killed, leading to the foundation of the Imperial (now Commonwealth) War Graves Commission.

Those immaculate cemeteries, which stand so sadly and yet so proudly all over northern France and Flanders today, are as much a monument to his vision as they are a reminder to us of the cost of such a terrible war.

Lt Gen Sir Barney White-Spunner KCB, CBE was Commander of the Field Army. He has written the story of The Household Cavalry, ‘Horse Guards’ (£30), and is bringing out a book on Waterloo next year

* Follow Country Life magazine on Twitter

-

‘It had the air of an ex-rental, and that’s putting it politely’: How an antique dealer transformed a run-down Georgian house in Chatham Dockyards

‘It had the air of an ex-rental, and that’s putting it politely’: How an antique dealer transformed a run-down Georgian house in Chatham DockyardsAn antique dealer with an eye for colour has rescued an 18th-century house from years of neglect with the help of the team at Mylands.

By Arabella Youens

-

A home cinema, tasteful interiors and 65 acres of private parkland hidden in an unassuming lodge in Kent

A home cinema, tasteful interiors and 65 acres of private parkland hidden in an unassuming lodge in KentNorth Lodge near Tonbridge may seem relatively simple, but there is a lot more than what meets the eye.

By James Fisher