The ship that was in two different centuries, two different years, two different months, two different days and two different seasons, all at the same time

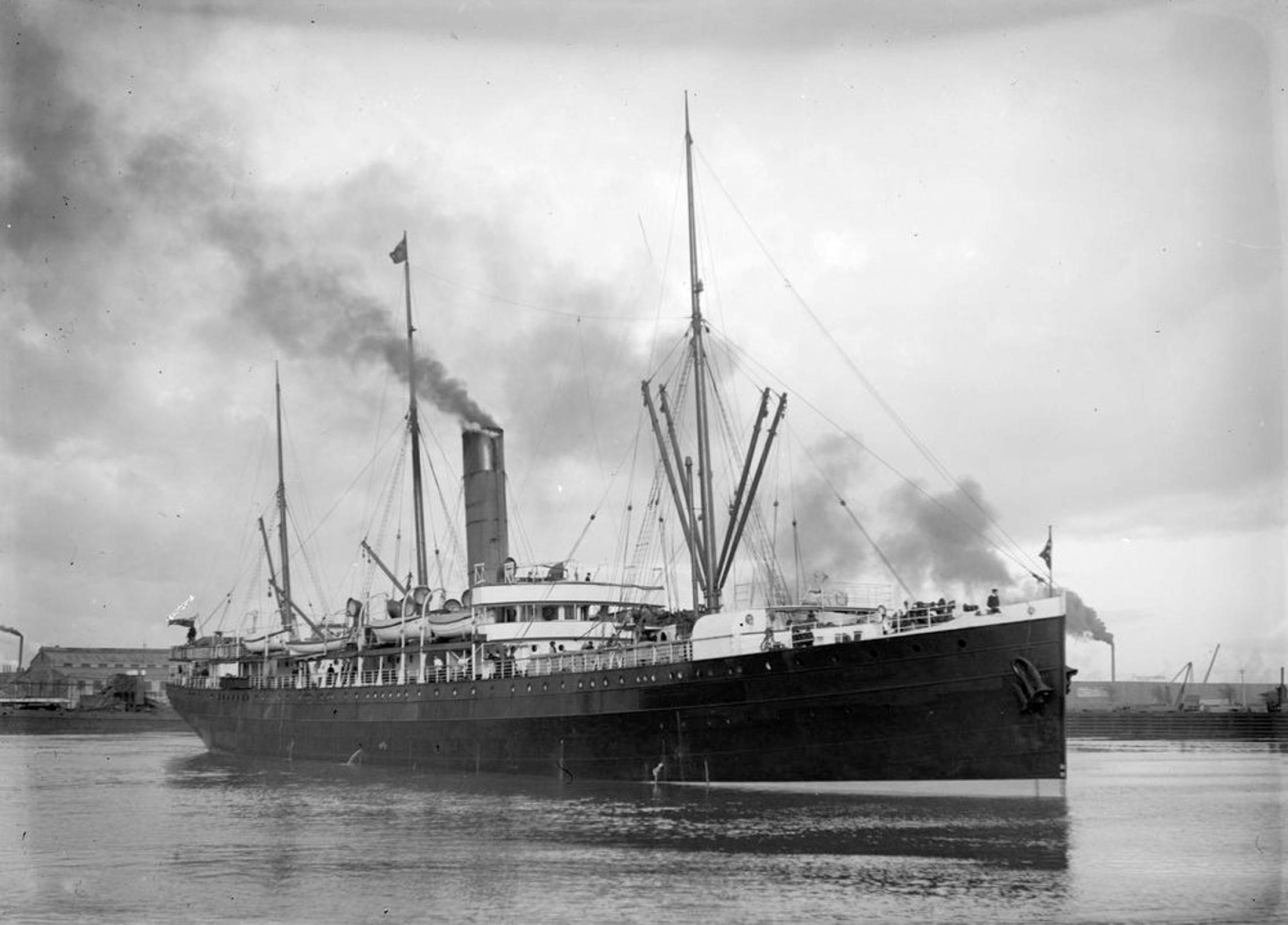

On December 31, 1899, the SS Warrimoo may have travelled through time — but did it really happen?

On October 1, 1884, forty-one delegates from 25 nations assembled at the Diplomatic Hall in Washington D.C at the invitation of the US President, Chester Arthur, their mission to establish the Prime Meridian. As it travels around the Sun, the Earth rotates on its axis in a counterclockwise direction (from west to east), which means that different parts of the globe receive the Sun’s direct rays at different times. The need for a world standard for time and date only became apparent with the boom in global commerce, the growing interdependency between nations, and the increasing sophistication of communications systems.

The delegates voted by 22 votes to one to accept the meridian passing through the Observatory at Greenwich as the Prime Meridian, from which all longitudes would be calculated both east and west until the 180⁰ meridian was reached. San Domingo, now Dominican Republic, voted against Greenwich’s primacy with Brazil and France abstaining, the latter not adopting the Greenwich meridian on their maps until 1911.

There would be twenty-four time zones of 15 degrees each, twelve running eastwards from the Greenwich meridian to the 180⁰ meridian and twelve westwards. All countries would adopt a universal day, lasting twenty-four hours, beginning at midnight in Greenwich and counted on a 24-hour clock.

The conference also selected the 180⁰ meridian as the location for the International Date Line (IDL), marking the boundary between one calendar day and the next, passing through the sparsely populated Central Pacific Ocean and causing, at least to western eyes, least inconvenience. Crossing the IDL eastwards would decrease the date by one while moving westwards would advance it by one. It was never defined in international law, allowing countries through whose waters it passed to move it for their convenience, giving it an erratic path on a map.

One of the most recent changes occurred when Samoa effectively erased December 30, 2011 from the country’s calendar as it crossed westwards over the IDL. Crowds gathered around the main clock tower in the capital, Appia, and cheered as the clock struck midnight on December 29th, instantly transporting them to New Year’s Eve. Geographical proximity creates some oddities. Just two miles of the Bering Sea separate Big Diomede Island, part of Russia, from Little Diomede, part of the US, but as the IDL passes between the two, the Russian territory is always one day ahead.

For sailors and passengers alike crossing the IDL was a high water mark in a voyage across the expanse of the Pacific Ocean. Mark Twain, travelling on the SS Warrimoo, from Vancouver to Sydney in 1895 at the start of a world lecture tour, wrote about his experience in Following the Equator (1897), characteristically pointing out the absurdities that arose.

'While we were crossing the 180th meridian', he wrote, 'it was Sunday in the stern of the ship where my family were, and Tuesday on the bow where I was. They were there eating half of a fresh apple on the 8th, and I was at the same time eating the other half of it on the 10th — and I could notice how stale it was, already'.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

'A child was born in steerage at the precise moment, he reported, and there was no way to tell which day it was born on. “The nurse thinks it was Sunday, the surgeon thinks it is Tuesday'

A child was born in steerage at the precise moment, he reported, and there was no way to tell which day it was born on. 'The nurse thinks it was Sunday, the surgeon thinks it is Tuesday'. Twain feared for the child’s future, surmising that the doubts as to its birth date will lead to 'vacillation and uncertainty in its opinions about religion and politics, and business, and sweethearts' making it characterless and doomed to fail in life.

On the same voyage, Twain crossed the equator, but for mariners the Holy Grail was to cross the Equator at the 180th meridian, a feat that entitles a sailor in the US Navy to become a Golden Shellback. An even rarer honour is the Emerald Shellback or Royal Diamond Shellback, bestowed on American and Commonwealth sailors respectively who have crossed the Equator at the Prime Meridian.

Although immortalised by Twain, the SS Warrimoo entered the annals of history in its own right in a most extraordinary way. Initially, there was little unusual aboard ship on the evening of December 31, 1899. The ship was mid-Pacific, en route to Sydney, and the navigator was observing the stars to calculate its precise position. As usual, he gave the results to the master, Capt John Phillips, but it was the first mate, Symons, who realised the significance of their position, LAT 00 31′ and LON 179 30′. They were just a few miles from the intersection of the Equator and the IDL, presenting the chance to perform a rare nautical feat that would knock golden and even emerald shellbackery into a cocked hat.

Calling his officers together to check and double check the ship’s position, Phillips adjusted the Warrimoo’s position slightly to hit the precise spot, reduced engine speed and, aided by calm weather and clear skies, at midnight the ship lay precisely on the intersection of the Equator with the IDL.

The consequences were positively mind-blowing. Its bow was in the Southern Hemisphere and in the middle of summer, while its stern was in the Northern and in midwinter and, as it was straddling the IDL, it was also in the eastern and western hemispheres. The date at the rear of the ship was December 31, 1899 but at the front it was New Year’s Day, 1900. In other words, the Warrimoo was in two different days, two different months, two different years, two different seasons and two different centuries all at the same time. Just for good measure, it was also in all four hemispheres at once.

The $64,000 question, though, is whether it really happened. The Warrimoo was in the area at the time, The Sydney Morning Herald reporting in January 1900 the arrival of the ship after setting out from Vancouver on December 15, 1899, albeit that the equator was crossed on December 30th and without any mention of when the IDL was crossed.

It was not until 1942 that it emerged that the SS Warrimoo had crossed the equator and IDL on the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve, 1899. An article in the Ottawa Journal reported that Capt Phillips, by then long retired and living in Sydney, had produced 'the record of a remarkable achievement' after browsing through his old log books. However, there seems to be no other documentation to corroborate his claim.

Sceptics question whether with the navigational techniques used at the time Phillips could have, with absolute certainty, positioned the Warrimoo at the right place at the right time. And then there is the century question. The common scientific and historic consensus is that a century consists of 100 years and that, as there was no year zero, the first century of the Christian Era ran from 1 to 100, the second century from 101 and so on. Rather than greeting a new century the bow of the Warrimoo was merely entering the final year of the 19th century.

The Golden Shellbacks show that crossing the equator at the IDL at sea is rare, but not unusual, and while passing from one month to another and from one year to the next at the same time is rarer still, the Warrimoo’s story loses even more of its sheen when it is stripped of its century straddling element. However, never let the facts get in the way of a good story.

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?

The history of the Olympics is full of curious events which only come to prominence once every four years. Martin

Curious Questions: Why do all of Britain's dolphins and whales belong to the King?

More species of whale, dolphin and porpoise can be spotted in the UK than anywhere else in northern Europe and

Curious Questions: Do dock leaves really cure nettle stings?

Renowned as a ‘land robber’, docks don’t have much going for them, other than alleviating nettle stings — but do

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.