The remarkable tale of the bathing machine

When the British fell in love with the seaside, they invented a mobile building to convey them to the water. Kathryn Ferry tells the remarkable tale of the bathing machine.

From his tall plinth on Weymouth seafront, the towering figure of George III in his finery surveys the sandy bay he helped popularise. The Dorset resort is still defined by its Georgian buildings erected in the wake of the King’s first visit in 1789, but, like every good seaside town, Weymouth has been shaped by the shifting tastes of generations of tourists and the architectural layers of multiple eras. Even the beach huts here are historic and varied and there is much to absorb.

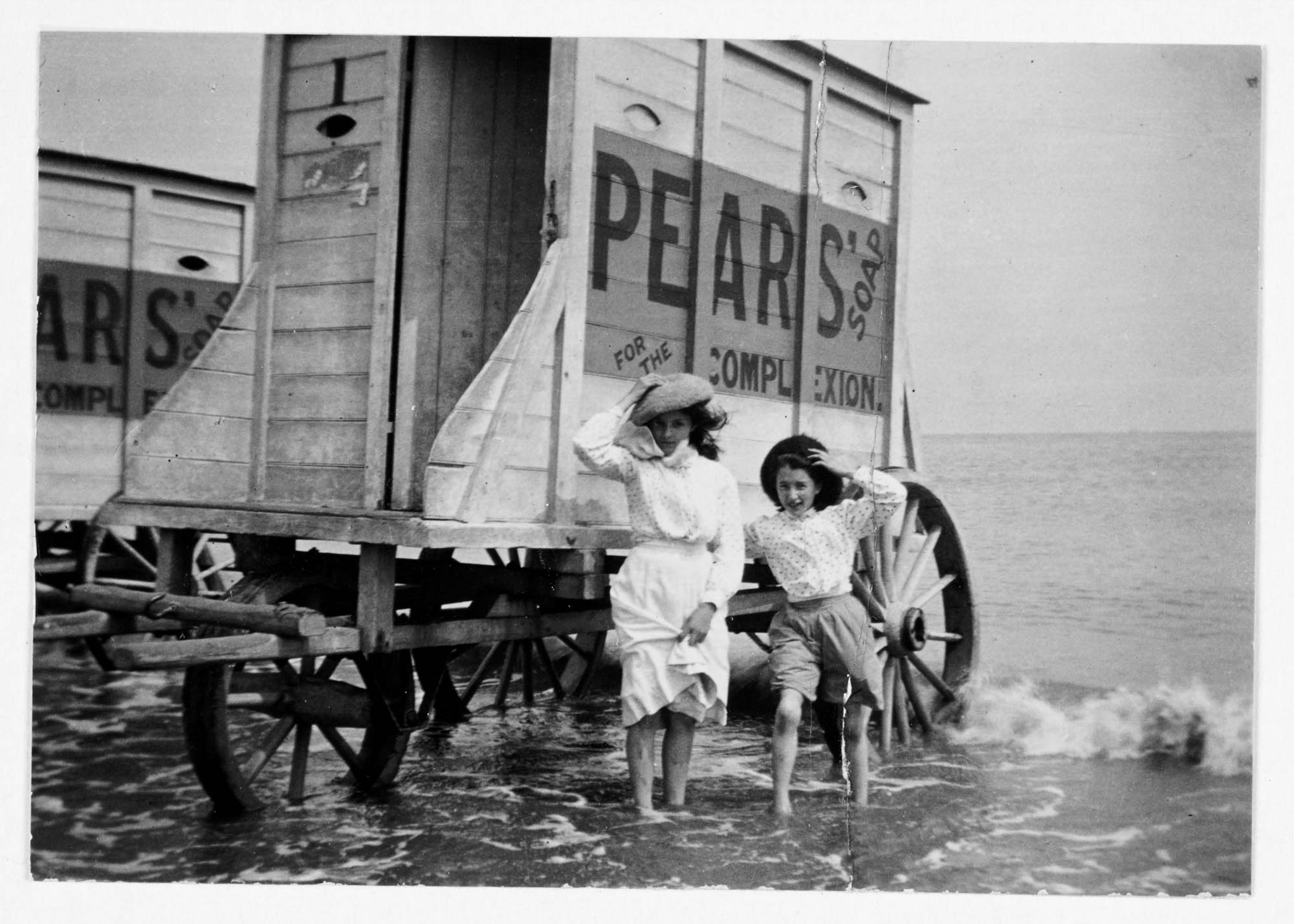

Beyond the King’s gaze, there are terraced post-war chalets around a paddling pool, rows of mock-Tudor style huts from the 1920s and a run of concrete huts with cast-iron columns that are unusual for being Grade II listed and for having a bowling green built on top of them. Along the beach itself are unique huts without walls; their design features a lockable box at the back in which is kept the canvas that provides privacy and a form of structural integrity when the owner is in residence. It is, however, the wheeled hut permanently stationed next to George III’s statue (Fig 9) that is the ancestor of them all, the much-derided, but surprisingly long-lived bathing machine (Fig 1).

For nearly 200 years, bathing machines, essentially mobile changing rooms, could be found all around our coastline, the interlocutors between Britons and the sea, a form of movable architecture that demonstrated as much variety in design as do their modern beach-hut successors. The bathing machine was a product of the 18th-century saltwater cure, aimed at helping patients who were undergoing the regimen of briny dips prescribed by their physicians. Georgians who journeyed to the coast did so for their health, convinced by both the lack of alternatives and the increasingly fashionable status of a seaside visit.

The North Yorkshire town of Scarborough (Fig 2) can claim to be the world’s first modern seaside resort, although it was not until several decades after the 1626 discovery of an iron-rich mineral spring in the cliffs above South Bay (later the focus of a spa or ‘spaw’) that the presence of the sea became more than a point of coincidence.

In his 1667 book Scarborough Spaw, Dr Robert Wittie of Hull asserted that the sea cured gout, balanced the humours and, in a thankfully unspecified manner, ‘killed all manner of worms’. The earliest known image of a bathing machine also comes from Scarborough and shows a solitary structure at the water’s edge, with small wheels and a pyramid roof. In a 1735 engraving by John Setterington, the door is held open by a footman as a naked man emerges ready to face his treatment in the lapping waves.

Ten years later, the same distinctive carriage was depicted by artists Samuel and Nathaniel Buck, now surrounded in the water by wheeled huts with gabled roofs. Uncertain how to describe this coastal novelty, the Bucks wrote of ‘A curious contrivance of Wooden Houses moveable on wheels’.

Other places adopted this means of conveying health-seekers across the beach and, as early as 1721, Nicholas Blundell, master of Little Crosby on Merseyside, recorded that he had escorted an acquaintance ‘to Leverpoole & procured him a Place to lodg at & a Conveniency for Bathing in the Sea’. In the 1750s, Dr Richard Russell of Lewes sent his aristocratic patients to the small fishing community of Brighthelmstone, now Brighton in East Sussex, to use what he called the ‘bathing chariots’.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The mechanical innovation that led to the generic term of bathing ‘machine’ happened in the Kentish resort of Margate in 1753 (Fig 3). A local Quaker by the name of Benjamin Beale designed a form of collapsible canvas hood for the rear of his vehicles. When the horse and driver had reached sufficiently deep water, about chest height according to one observer, the hood would be let down over its four hoops to create an enclosed bathing area of 8ft–13ft. Bearing in mind that women’s bathing costumes, if they were worn, were little more than shapeless sacks and men generally divested themselves of all clothing when being trundled into the waves, it is perhaps unsurprising that Beale’s modesty hood met with rapid success. In 1754, it was being advertised at Deal and Broadstairs as ‘the original NEW-INVENTED MACHINE for Bathing in the Sea’ and the name stuck.

Not everywhere adopted the hood and poor George III might well have regretted its absence at Weymouth when he went for his initial dip when recuperating from his first attack of the porphyria that caused his madness. Royal patronage was a massive boon for the town and, according to Fanny Burney, diarist and Keeper of the Queen’s robes, the locals had gone into patriotic overdrive with children and labourers sporting the motto ‘God Save The King’ in their hat bands. The women charged with ‘dipping’ His Majesty under the waves had stitched the same words in large letters around the waists of their flannel dresses and, when the disrobed and wig-less King stepped out of his bathing machine, a band of musicians emerged from a neighbouring machine to play the national anthem. The rest of his cure passed off more quietly and George III returned to Weymouth almost every summer between 1791 and 1802. A special bathing machine was created for his use, octagonal in plan and mounted on a sturdy chassis with large wheels, with the Royal Arms above the door. It is a replica of this that now resides on the seafront.

George IV chased his more racy seaside pleasures at Brighton, but sadly never commissioned a personal bathing machine to mirror the exuberant Indo-Chinese design of his Royal Pavilion. Queen Victoria rejected the crowded beaches of Sussex to enjoy her first dip in the sea from the calm of her seaside retreat on the Isle of Wight. Her bathing machine at Osborne House has been restored by English Heritage, although not all its original features have been reinstated. When first crafted by a Portsmouth coach builder, the 12ft by 7ft cabin had window and door handles of silver and, hung from a rail around the canopy shading its steps, a ‘silken net to prevent the Royal children from getting into the sea’. For maximum comfort, the wheels were eased by hand-powered winch along granite channels in a specially constructed slipway.

By the mid century, bathing machines had been universally adopted as the only morally correct way for Victorians to enter the sea. Pleasure replaced health as the prime motivation for seaside visits, but this did not mean a free-for-all; the distance to be maintained between male and female machines was specified in local bye-laws and anyone wishing to do more than paddle was required to pay for hire of a machine. Changing on the beach was simply not permitted (Fig 5).

By the 1890s, holidaymakers had begun to challenge the status quo, but, as the Architectural Review pointed out in July 1964, as the ‘first piece of veritable seaside furniture’, the bathing machine ‘had a potent visual and social influence on the beachscape’ (Fig 7). Sam Smith’s article considered bathing machines as a type of ‘folk art’ and the evidence for their local quirkiness means they can rightly be considered a form of seaside vernacular. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Northumberland, where the machines at Tynemouth and Whitley Bay (Fig 4) were clinker-built, fashioned like boats with their horizontal timber planking bent into shape between arched door openings. Along the East Anglian coast, from Felixstowe to Clacton, wooden walls were strengthened on the outside by an exposed frame that appeared as decorative arcading. A similar method of construction was used for threshing machines in the agricultural hinterland, suggesting an overlap of techniques and probably labour.

The standard Sussex bathing machine changed little over time, causing an 1871 critic, styling himself Piscator, to scornfully describe the Brighton type as ‘an overgrown dog kennel’. Rival operators on the same beach used colour to make their machines distinctive. In 1999, the cabin of a machine from the Hounsom family fleet was found on an allotment at Eastbourne, having been sold off in the 1920s. During its restoration by the owner of the Langham Hotel, paint analysis revealed that it had originally been painted in vertical stripes of bright red and yellow. The most eccentric operator was to be found at Ramsgate in Kent where, in 1856, ‘Pearce — the poet Pearce — owns gorgeous, decorated machines, some striped yellow and red, like the Arab’s garb, others painted green as an opening bud, others blue as the eyes of Ondine. The bard Pearce is not ashamed of what he is, but has painted over his machines in bold yellow letters “P. H. Pearce, poet”’.

Artistic representations of the beach can offer further design insights, for example in the 1914 painting Along the Shore by Joseph Southall, in which a trio of fashionably dressed women and a child walk in front of Southwold bathing machines, one pale green, the other pale pink. By the First World War, men and women were allowed to enjoy so-called ‘mixed bathing’ and many bathing machines had already taken up a static position on the sands, no longer being pulled in and out of the water for each customer (Fig 6). As soon as bathing costumes were allowed to be worn on the beach and not only in the sea, they could fully embrace their modern potential as fashion garments.

In the 1880s, Felixstowe in Suffolk pioneered the purpose-built beach huts that would ultimately render the bathing machine obsolete. When Eric Ravilious painted the empty machines lined up along Aldeburgh beach in 1938, he did so as remnants of a passing age. Interestingly, the double-compartmented blue and white machines, with their highlights of red on barge boards and finials, were described in the 1964 Architectural Review article as ‘undoubtedly the loveliest of all’.

By 1945, thousands of bathing machines had been scrapped or re-purposed. At Weymouth, the royal machine remained in regular use by members of the bathing public until 1914. Two years later, it was auctioned off; the purchaser, Mr Clifford Chalker, removed the wheels and turned them into candlesticks, then converted the changing cubicle into a summerhouse. This was dismantled in 1930 and put into storage, finally coming out in 1971 when it was donated to Weymouth Museum.

In recent decades, the renewed popularity of beach huts has seen them transformed into icons of the Great British Seaside. In common with their wheeled ancestors, they display an eclectic mix of place-specific designs and add a much-loved splash of colour to our seafronts. If you know where to look, you can still find former bathing machines in use as modern-day beach huts. On the sands at Southwold, a couple of day huts betray their origins in the double doors that once gave access to the separate changing rooms of a bathing machine (Fig 8).

More impressively, at Ventnor, on the Isle of Wight, the Blake family has been in business since 1830. When fashions changed, the Blakes removed the wheels from their bathing machines, cut them in half and turned them into the beach huts that are still eagerly rented out today. Despite their simplicity and diminutive scale, these huts hold within their walls the very story of how we fell in love with the sea.

Curious Questions: When and why did we start bathing in the sea?

Despite the British love of seafaring, voluntarily taking a dip in the sea was almost unheard of until relatively recently.

Britain's best seaside architecture: The playful details that shaped our coastal towns, from funicular railways to Victorian masterpieces

What is it that makes the buildings of the seaside so distinct? Kathryn Ferry looks at the vibrant architecture of

-

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)With more buyers looking at London than anywhere else, is the 'race for space' finally over?

By Annabel Dixon

-

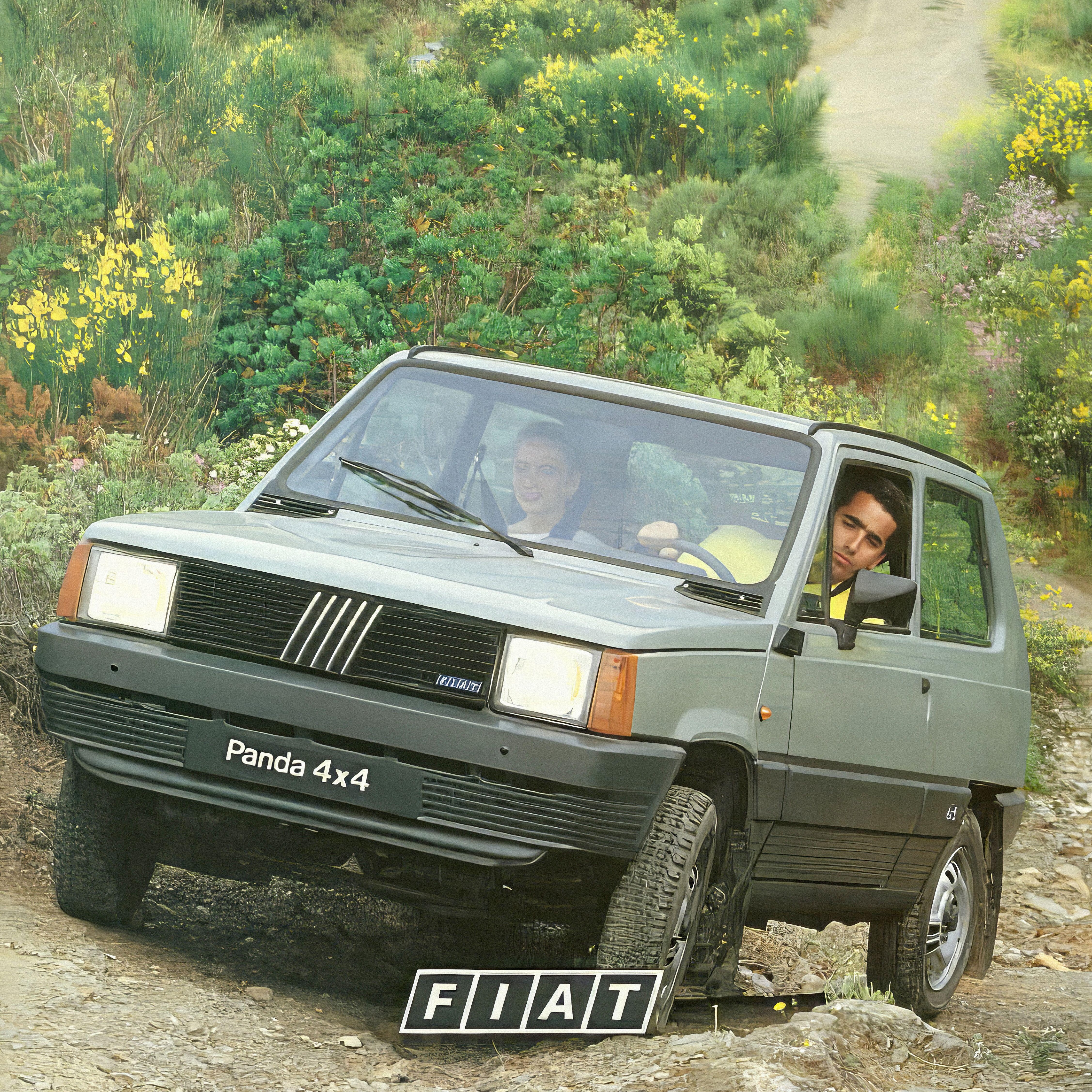

Helicopters, fridges and Gianni Agnelli: How the humble Fiat Panda became a desirable design classic

Helicopters, fridges and Gianni Agnelli: How the humble Fiat Panda became a desirable design classicGianni Agnelli's Fiat Panda 4x4 Trekking is currently for sale with RM Sotheby's.

By Simon Mills