The real-life farm and animals that give life to George Orwell's Animal Farm

It's 75 years since George Orwell published Animal Farm, and while the book is an allegory based on Soviet Russia it still shows off the writer's surprising first-hand knowledge of real farm life. Julie Harding explains more.

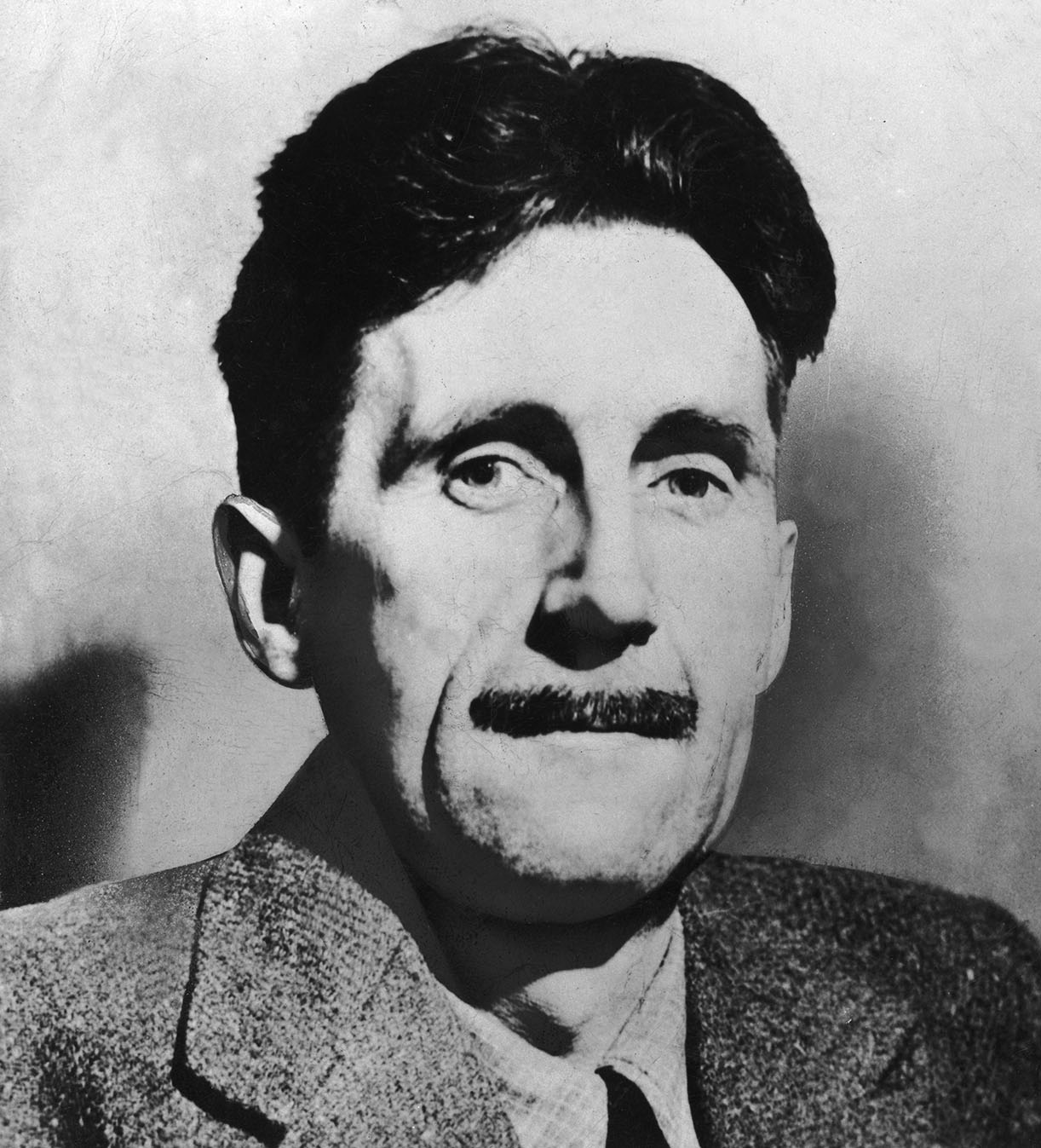

‘I saw a little boy, perhaps ten years old, driving a huge cart-horse along a narrow path, whipping it whenever it tried to turn. It struck me that if only such animals became aware of their strength we should have no power over them.’

When George Orwell wrote this passage in his preface to the Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm in 1947, explaining the genesis of his allegorical novella, the book had already been read in Britain and beyond for almost two years.

Animal Farm would become Orwell’s first commercial success and the one that would begin to cement his reputation as a literary giant. He would follow it with his dystopian Nineteen Eighty-Four, a novel he wrote when isolated from the rest of the world on the Hebridean island of Jura, dying of tuberculosis.

Animal Farm’s path to the bookshops was strewn with obstacles. Several publishing houses shied away from the scathing satire on the Soviet Union, Britain’s wartime ally — a political ‘potato’ that was way too hot to handle as the author pulled the last sheet of manuscript paper from his typewriter in 1944, with VE Day and the erection of the Iron Curtain just around the corner. However, when Fredric Warburg ran with it, the public purchased in their droves, the first edition of 4,500 copies apparently selling out within days.

This public was beguiled by Animal Farm’s moral fable — with echoes of Aesop and political-allegory parallels to Gulliver’s Travels — in which a bunch of animals, led by a pig (Old Major), stages a peaceful coup, overthrowing Farmer Jones, but subsequently living far from happily ever after as another pig (Napoleon), who takes control of the farm republic, becomes ever more nefarious and merciless in his exploitation of the other livestock.

In the ensuing decades since its publication, Animal Farm has become a standard school text, with subsequent generations familiar with Orwell’s readable, jaunty prose style, ‘hidden’ meanings and the animals’ alter-egos.

Animal Farm might have been consigned to the dusty attics of history long ago had Orwell’s rendering of his animal protagonists not been so on point and credible — the sheep lemming-like, the pigs intelligent and top of the pecking order and the aged donkey, Benjamin, stubborn and knowing.

They are rooted in Orwell’s real farming experiences and they demonstrate his profound and deep-seated understanding of animal character traits, behaviour and husbandry requirements. ‘Major was already ensconced on his bed of straw… He was twelve years old and had lately grown rather stout, but he was still a majestic-looking pig, with a wise and benevolent appearance in spite of the fact that his tushes had never been cut,’ Orwell writes with a farmer’s knowledge at the beginning of the book.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘My father was very observant of everything, and would quite quickly absorb the various characteristics of farm animals and subsequently pigeonhole them in his mind as to how clever or not they appeared to be,’ reflects Richard Blair, the son Orwell (real name Eric Arthur Blair) adopted aged three weeks in 1944, with his wife, Eileen.

‘I guess in Animal Farm, he started with the pigs and placed the animals in descending order as he saw them.’

According to Mr Blair — and also D. J. Taylor, who wrote the prize-winning biography Orwell: The Life — Orwell’s fascination with Nature and the animal world was sparked in childhood and remained undimmed up to his death in 1950. When he was young, he would explore the countryside around the family home in semi-rural Shiplake, near Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, where the sights, sounds and smells of the farmyard would have been all around.

Horses played a part in his life. Living in Burma during the 1920s, Orwell would have observed them at close quarters, both as a mode of transport and in his role in the Indian Imperial Police, connections that helped his equine portraits to sparkle with life. He writes fondly of the horse in Animal Farm:

‘Boxer was an enormous beast, nearly eighteen hands high, and as strong as any two ordinary horses put together. A white stripe down his nose gave him a somewhat stupid appearance, and in fact he was not of first-rate intelligence, but he was universally respected for his steadiness of character and tremendous powers of work.’

Between 1936 and 1940, Orwell famously lived at The Stores in the Hertfordshire village of Wallington, where he introduced livestock into his everyday life.

‘The Stores was where Orwell was able to put into practice his accumulated knowledge of gardening and, as there was a little ground for livestock, he began to bring in chickens, for eggs and for ultimately eating,’ remembers Mr Blair. ‘He had a fondness for goats as he preferred goats’ milk to cows’.

‘Was he successful as a smallholder? Well, I think we have to agree that he was no professional, but very much in the category of an enthusiastic amateur. He was often given tips by the local people on how to perform physical tasks, such as double digging, how to make shelter for the chickens and fertiliser for his vegetables.’

In a rare and iconic picture, Orwell is in the garden at The Stores, crouching down submissively, feed bowl in hand, close to his goat Muriel. At the moment Dennis Collings clicked the camera button, she turned her horned head away from her owner.

‘My father was very fond of Muriel and, snakes notwithstanding [Orwell once slit open an adder from head to tail], he was very fond of all his animals and I think that he had great empathy with them. His were all well looked after, but he was of that generation where they were also a source of food. He could be pragmatic about animals that could be slaughtered and eaten, such as chickens, geese, lambs and pigs. He saw no conflict in this regard.’

Muriel is the presumed precursor of her namesake in Animal Farm, a literate white goat, but Orwell expends far more words to describe the real creature in his letters and diaries than he does the fictional one in his novella. His diary entry of May 31, 1939 runs:

‘M’s mating no good. When bringing her back found she had not been milked since taking her there (ie, 48 hours) and her udders were very distended. Milked her and obtained a quart.’

The diaries also make extensive references to his hens and their egg-laying capabilities. Seventeen laid on May 31, for example, and ‘sold 50 at 2/- a score’. ‘[Orwell’s domestic diaries] offer crucial insights about his personality, his literary style, his love of the simple life, his emphasis on the constant struggle to see clearly “what is in front of one’s nose”,’ writes The Orwell Society chair Prof Richard Keeble on www.orwellsociety.com.

Mr Taylor, who has been working on new critical introductions to all six of Orwell’s books (copyright expires this year) as well as compiling Orwell: The New Life, set for publication in 2023, adds: ‘Orwell’s relationship with animals was really quite intense. After Eileen died, a friend complimented him on the care he took of Richard, and Orwell said: “Well, I’ve always been good with animals.” He also said “some of my best experiences have been with animals”.’

Orwell evidently gleaned much of his animal-husbandry knowledge from his voracious reading of Smallholder magazine, to which he subscribed. He would snip tips from the pages and stick them in his diaries. Agricultural periodical Farmer and Stock-breeder even merits a mention in Animal Farm: ‘Snowball had made a close study of some back numbers… which he had found in the farmhouse, and was full of plans for innovations and improvements.’

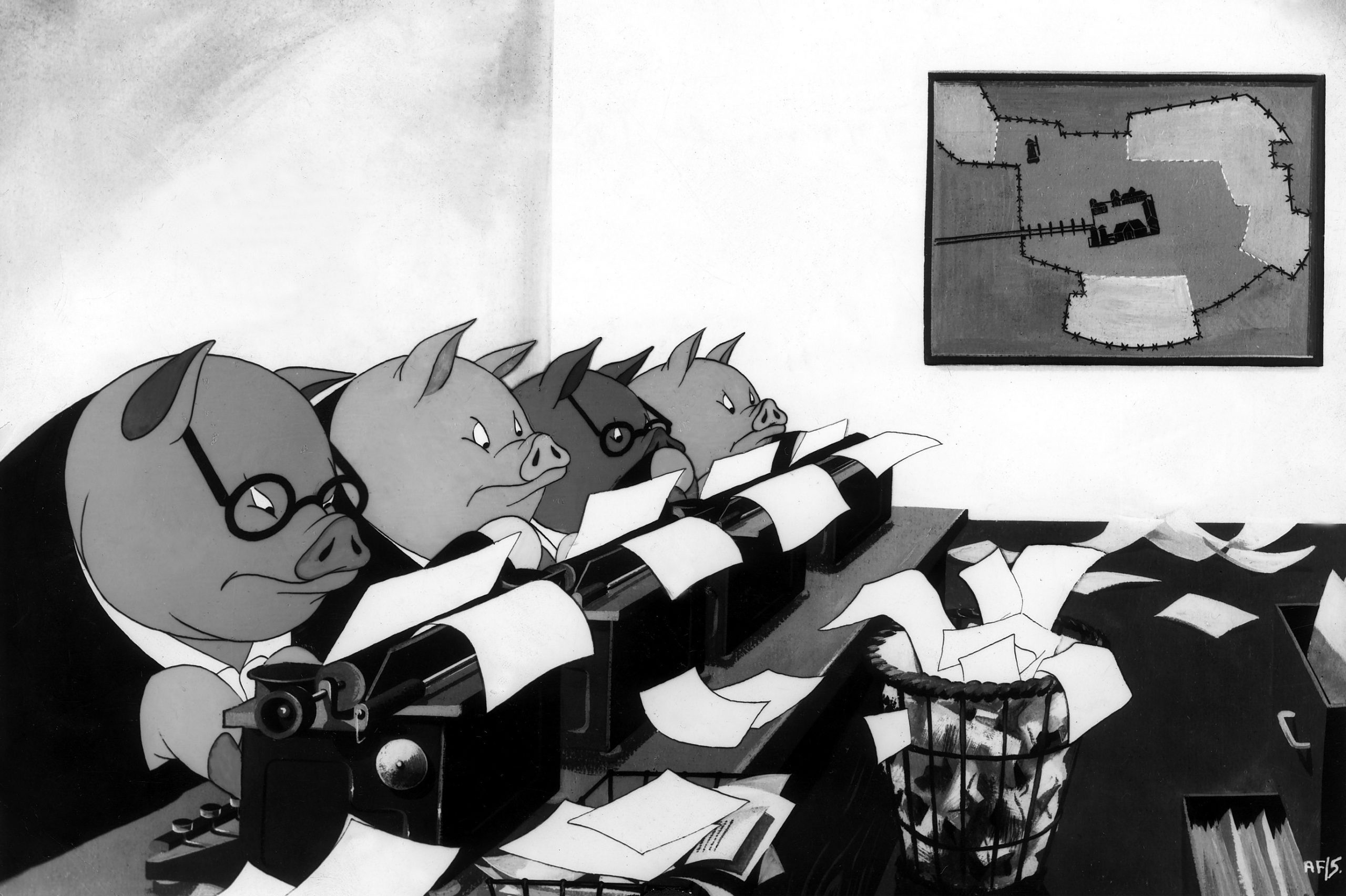

Pigs, however, were a step too far for Orwell. Although Eileen would sign letters with her nickname, ‘Pig’, Orwell’s fondness for livestock didn’t extend to the stocky-bodied omnivores. ‘He writes from Jura something along the lines of, “Pigs are disgusting brutes. We’re really looking forward to this one going to the butcher”,’ notes Mr Taylor.

Indeed, although specific evidence linking Orwell closely to larger livestock types before Animal Farm is spartan, plenty exists after his arrival at Barnhill on Jura. ‘Barnhill was essentially a farm and, eventually, we had live-stock there: chickens, sheep (not many) and a few cows, one of which was tested in order to give TB-free milk,’ Mr Blair recalls.

The late John Hammond waxes lyrical in A George Orwell Companion: A Guide to the Novels, Documentaries and Essays about the ‘skilful manner’ in which Orwell renders animal portraits in Animal Farm:

‘It is a book that could only have been written by an author who liked animals and understood their ways and foibles. Orwell clearly sympathises with the animals at each stage of their experiences: this empathy, this ability to reach inside their minds and describe their thoughts and emotions, as if from the inside, is one of the most attractive features of the story and is one of the many reasons why the satire is so successful. A story in which the animals were merely caricatures without individual traits would not have been nearly so effective.’

Who’s who in Animal Farm: the animals’ alter egos

The pigs

- Napoleon (tyrannical rebellion leader): Joseph Stalin

- Snowball (eloquent and intelligent, later scapegoat for the ills on Animal Farm): Leon Trotsky

- Old Major (wise and articulate, the initial inspiration for rebellion): Vladimir Lenin or Karl Marx

- Squealer (manipulative, Napoleon’s mouthpiece): Vyacheslav Molotov, Stalin’s head of communications and propaganda

The horses

- Boxer (loyal 18hh workhorse): Russia’s working classes

- Mollie (shallow, materialistic, pulls a carriage): the bourgeois middle classes

- Clover (a motherly mare): the women of the revolution

The others

- The sheep: an acquiescent population

- The goat, Muriel: the educated working classes

- The donkey, Benjamin (insightful and cynical about the revolution): Orwell himself?

In praise of ponds, the water havens that 'teem with life as fantastic as anything in science-fiction'

A chance reading of George Orwell brought John Lewis-Stempel to the realisation that he'd neglected his own ponds. He explains

Credit: Alamy

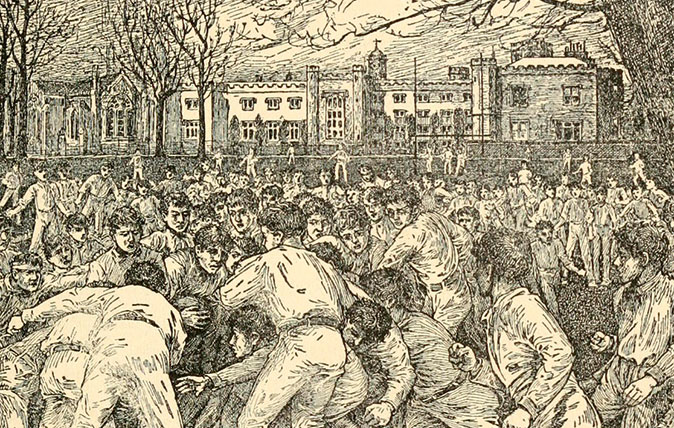

Stiff Upper Lip review: A book that asks 'powerful questions that parents can't ignore'

James Fergusson examines a passionate polemic against boarding school which raises serious questions.

Red telephone boxes: 7 fantastic alternative uses for a British icon

Distinctly British, but rendered obselete by the march of the mobile, the red telephone box is finding new purpose, as

What it's like to live for five days on an uninhabited Scottish island

Marooned on the uninhabited Scottish island of Scarba with only his terrier for company, Patrick Galbraith discovers the realities of

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.