Dover Castle, Kent: England's strongest castle

Jack Watkins looks at the story and impact of The Great Tower at Dover Castle, the imposing creation of Henry II that still stands strong almost 900 years later.

Dover, sitting squarely on the south-east coast of England, has long been recognised as one of the country’s most strategically important sites, with a hill fort built here during the Iron Age; behind and flanking it are eight miles of tall chalk cliff, rising almost vertically from the sea, broken only by the estuary of the River Dour as it empties into the sea. The Romans used this site to erect a tall lighthouse, which would later be attached to a Saxon church. After the Battle of Hastings, William the Conqueror strengthened the defences of the castle here, possibly rushing up the earth banks around the Saxon church and the Roman lighthouse.

In the 16th century, the pharos became a bell tower. Under Henry II, Dover became the first castle in Europe to be defended by concentric rings of high wall studded with towers: a principle of military architecture that was to endure until artillery forced the adoption of new defensive techniques in the 18th century. Dover Castle, which was in active military use until the Second World War, remains one of the first sights to greet foreign visitors arriving by sea.

How to visit Dover Castle

Dover Castle is right at the heart of Dover itself, adjacent to both the town centre and the ferry port — and thus easily accessible by road and rail. There's free parking for those not arriving on foot.

English Heritage members can get in free, but otherwise tickets are expensive — £24 for an adult — but as with Stonehenge, it's not one to begrudge: the castle is a major income generator for English Heritage, helping subsidise countless other sites across the country. And as well as the castle itself, there are also wartime tunnels, and underground hospital, Roman lighthouse and more within the 80 acre site. You can find out more at www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/dover-castle.

England's strongest castle

Whether the Norman Conquest of England was, as maintained by those notable authorities W. C. Sellar and R. J. Yeatman in 1066 And All That, ‘a good thing’ has been much debated by scholars. What’s not in doubt is that the Normans introduced the castle, a monument type that, in its purest medieval definition as a fortified noble residence, was unknown to the Saxon kingdom.

Within 100 years of the Conquest, according to R. Allen Brown, the great historian of the Norman period, castles ‘stood thick in every county’. In the haste to erect motte-and-bailey castles as quickly as possible, the towers were made of earth and timber, but, during the 12th century, the use of stone was increasingly common, signalling the arrival of the more substantial, thick-walled rectangular keeps.

It might seem that these hulking structures represented a technological advance. However, in France in AD1000, the master castle-builder Fulk Nerra, Count of Anjou, was already building massive stone keeps, such as Langeais on the Loire, the ruins of which still stand today. How fitting, therefore, that the building of England’s strongest, Dover Castle’s Great Tower, was not overseen by a Norman, but by one of Fulk’s Angevin descendants, Henry II, the first of the Plantagenet line on his ascent to the English throne in 1154.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Normans had erected a castle at Dover soon after William the Conqueror’s victory at Hastings, raised above a pre-existing Iron Age earthwork on the cliffs above the harbour. Little is known about this structure or of subsequent extensions before Henry II’s costly remodelling between 1179 and 1189.

Henry’s Great Tower, at 83ft high, with the corner towers rising 12ft higher and with walls up to 21ft thick, was a formidable stronghold. The King’s engineer Maurice also built an elaborate system of outworks, including an inner-bailey curtain wall with 14 square towers and two gatehouses. The concentric lines of defences were among the first of their kind in Europe; not for nothing did 13th century chronicler Matthew Paris dub the castle 'Clavis Angliae' — the key of England.

However, Dover Castle also expressed power and prestige that went beyond the purely militaristic. By the 1180s, the cult of St Thomas Becket had taken hold, drawing pilgrims from afar to worship at his Canterbury Cathedral shrine. In the late 1170s, notable visitors had included Count Philip of Flanders and Louis VII of France.

Henry, recognising an opportunity to create an impressive royal showcase through which to welcome Continental entourages, invested heavily in the castle’s service facilities, as well as in its defensive capabilities. The floors were linked by spiral staircases in the north-east and south-west corners and a plumbing system was based on an extensive network of lead pipes distributing water sourced from rainwater gutters and a well 289ft deep.

The tower was visually striking from a distance, with white Caen stone used in broad horizontal strips contrasting with the grey Kentish ragstone, which was also used as a construction material. Inside were two chapels, one of which was dedicated to St Thomas, with decorative stonework on the arches and capitals similar to those at the cathedral.

Elsewhere, decoration was relatively restrained and mainly confined to the second-floor halls. The tower’s fireplaces were a 15th-century insertion. In 2009, English Heritage redecorated the king’s hall, king’s chamber and other rooms to convey a sense of how they might have looked in Henry’s day. As historian Kevin Booth says, 'apart from the late-18th-century brick vaults over the upper halls, the tower remains much as conceived and built in the 12th century.'

This was the last of the mighty Dover Castle's rectangular keeps, and it has proved to be one of the most enduring, still looking down from the crest of the hill over the town today, offering an intriguing backdrop to walks along the famous white cliffs.

For opening times to Dover Castle, Kent, visit www.english-heritage.org.uk

Britain’s best medieval castles

They still stir the emotions in the 21st century, but imagine the impact the rectangular castle keeps of the Anglo-Norman period had in their heyday. The first of them to be built in this country was William the Conqueror’s White Tower in London, originally 90ft high to the battlements. Highly defensible, it also brought together the scattered structures of a traditional Continental palace, such as a hall, chapel and service rooms, under one roof.

The visceral impact of the White Tower — which was lime-washed by Henry III, hence being ‘white’ — is somewhat lessened by its incorporation within what was then called London Castle, and which we now know as The Tower of London, as well as by the later addition of cupolas on the corner towers and the insertion of large windows.

The near-contemporary Colchester Castle in Essex, was even larger than the White Tower, but lost its upper storey in a failed attempt at demolition in the English Civil War.

Rochester Castle, Kent, built in the reign of William II (1087–1100), remains the most visually intimidating of the surviving stone keeps.

These huge structures were expensive to build in comparison with motte-and-bailey castles. Inevitably, the latter proved less durable, although Berkhamsted Castle in Hertfordshire is a visually striking ruin.

Spectacular Scottish castles and estates for sale

A look at the finest castles, country houses and estates for sale in Scotland today.

Somerset born, Sussex raised, with a view of the South Downs from his bedroom window, Jack's first freelance article was on the ailing West Pier for The Telegraph. It's been downhill ever since. Never seen without the Racing Post (print version, thank you), he's written for The Independent and The Guardian, as well as for the farming press. He's also your man if you need a line on Bill Haley, vintage rock and soul, ghosts or Lost London.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025Wednesday's quiz tests your knowledge on literature, National Parks and weird body parts.

By Rosie Paterson

-

10 of Scotland’s most magical white sand beaches

10 of Scotland’s most magical white sand beachesWhat better day to celebrate some of Scotland's most stunning locations than St Andrew's Day? Here's our pick of 10 of the finest white sand beaches in the country.

By Country Life

-

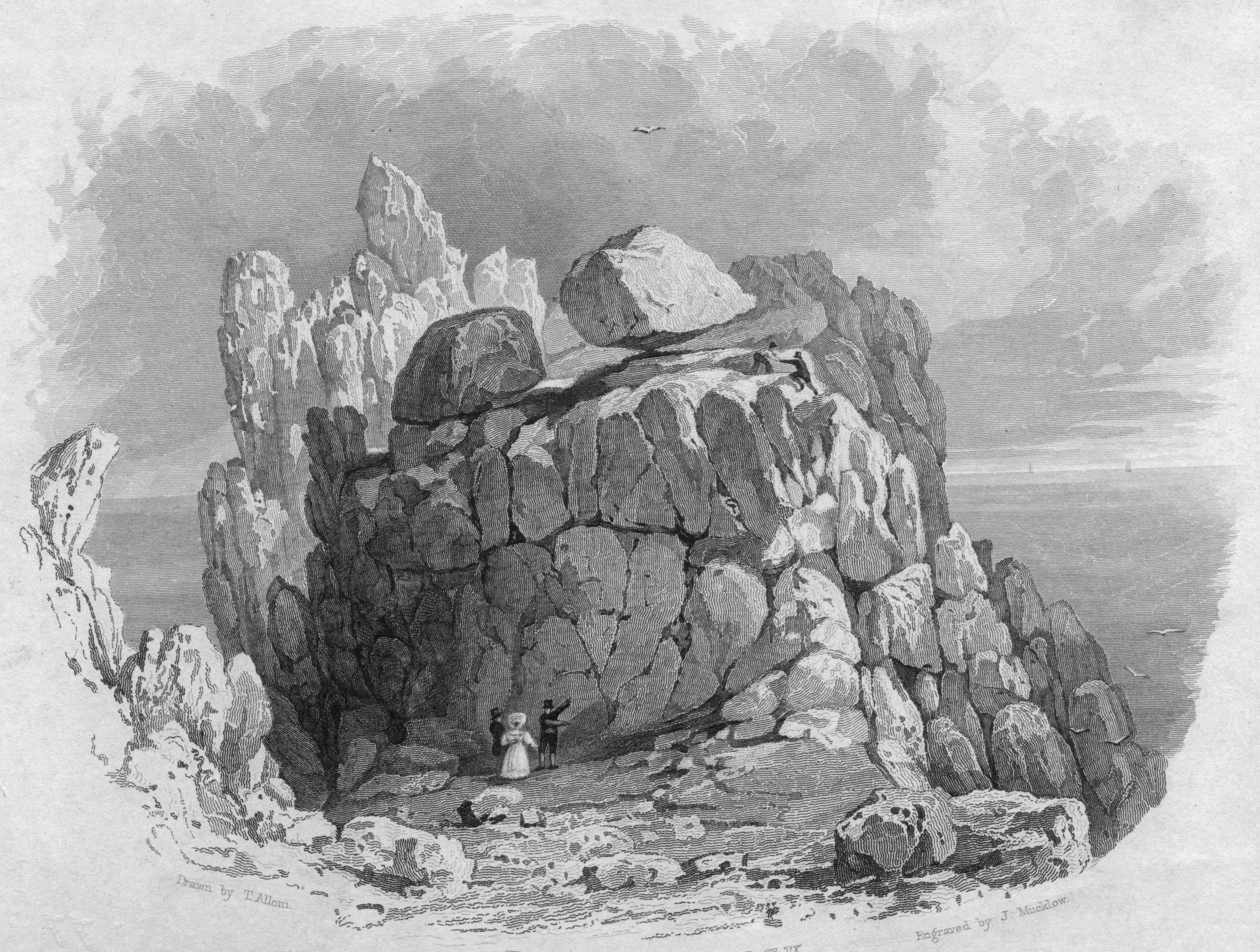

Curious Questions: Who dislodged Britain's most famous balancing rock?

Curious Questions: Who dislodged Britain's most famous balancing rock?A recent trip to Cornwall inspires Martin Fone to tell the rather sad story of the ruin and restoration of one of Cornwall's great 19th century tourist attractions: Logan Rock at Treen, near Land's End.

By Martin Fone

-

Henley Festival: 13 things you'll see at the 'posh Glastonbury'

Henley Festival: 13 things you'll see at the 'posh Glastonbury'Revellers in ball gowns and dinner jackets, turning up on board £200,000 boats to dance and party while knocking back magnums of vintage champagne? It can only be the extraordinary Henley Festival, the high-end musical extravaganza that's a sort of Glastonbury-on-Thames for the (very) well heeled. We sent Emma Earnshaw along to see what it was like.

By Emma Earnshaw

-

The best open air theatres in Britain

The best open air theatres in BritainAmid the sweet chestnuts, walnuts and cobnuts of a Suffolk farm, a natural amphitheatre has been transformed into a glorious sylvan venue for touring companies to tread Nature’s boards. Jo Cairdv pays a visit to the mesmerising Thorington Theatre, and picks out three more of the finest outdoor performance venues in Britain.

By Toby Keel

-

Alexandra Palace: How it's survived fires, bankruptcy and even gang warfare in 150 years as London's 'palace of the people'

Alexandra Palace: How it's survived fires, bankruptcy and even gang warfare in 150 years as London's 'palace of the people'Alexandra Palace has suffered every imaginable disaster, yet remains enduringly popular even a century and a half after its official grand opening. Martin Fone takes a look at the history of one of Britain's great public buildings.

By Martin Fone

-

Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland: The spectacular border town with a castle that changed hands 13 times

Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland: The spectacular border town with a castle that changed hands 13 timesBerwick-upon-Tweed spent centuries as a pawn in Anglo-Scottish conflict; today, it's a charming border town with spectacular sights. Clive Aslet takes a look.

By Clive Aslet

-

Ewelme, Oxfordshire: The medieval almshouses set up by Chaucer's grand-daughter and still running today

Ewelme, Oxfordshire: The medieval almshouses set up by Chaucer's grand-daughter and still running todayCountry Life's 21st century Grand Tour of Britain stops off at the remarkable church and almshouses at Ewelme, Oxfordshire.

By Toby Keel

-

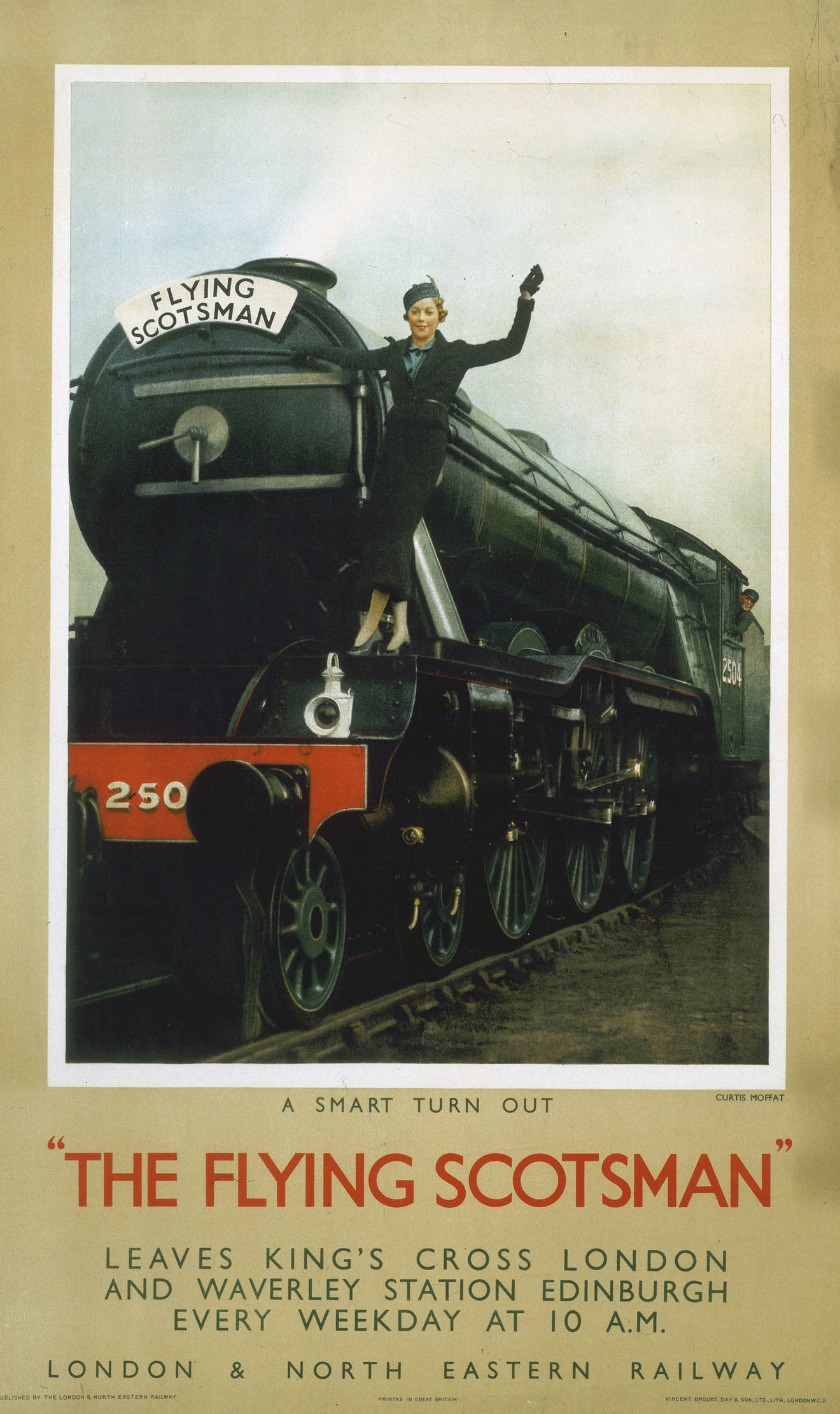

The Flying Scotsman: How the first 100mph locomotive became the most famous train in the world

The Flying Scotsman: How the first 100mph locomotive became the most famous train in the worldThe first train to officially hit 100mph may not even have been the first, and didn't hold the rail speed record for long; yet a century later its legend is undimmed. Jack Watkins celebrates the Flying Scotsman.

By Jack Watkins